Readers, Writers, Scholars ~ Symposium ~ 27 September 2013

Patchwork Gothic

From its beginning, gothic has been something of a patchwork. Hybrid in terms of genre, the first gothic tales stitched together medieval and historical romance, with the novel of manners, and supernatural and sensationalist tales from chapbooks and ballad sheets. Eighteenth century gothic was a new literary vogue, but it was also something reconstituted, a repetition of past forms and stories.

The patchwork nature of gothic’s use of the past is embodied in Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill.

Horace Walpole – one of the first writers to adopt the label ‘gothic’ for his works – constructed the villa - Strawberry Hill - in Twickenham between 1749 and 1776. The building was part cathedral, part castle, outlandish in style and irregular in design, inspired by both history and fairy-tale. Strawberry Hill was also an on-going project, added to, extended and developed over a period of thirty years. Inside housed Walpole’s vast collection of antiquities, including books, art works, curios and bric-a-brac from a vast array of periods and styles, ranging from the worthless to the priceless. Both house and collection inspired Walpole to write the very first gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto, in 1764. The novel may have initiated the gothic genre, but – like the house Walpole built - it was formed out of a hodgepodge of materials from the past. Stitching together elements of old poetry, drama and historical narrative, Otranto tells the story of the ruthless (and often ridiculous) tyrant, Prince Manfred who will do anything to hold on to the castle and title he has gained by nefarious means. The novel includes an ancient curse, ghostly apparitions, talking portraits, numerous mistaken identities, the return of long lost family members and several shockingly violent deaths – all framed by a preface that claims the novel is copied from a genuine medieval manuscript.

That Gothic texts are produced by stitching together old threads reminds us that the origin of the word ‘text’ is to be found in the Latin ‘textus’ and ‘texere’ – words which mean a piece of woven cloth and ‘to weave.’ For the literary theorist, Roland Barthes, all texts are ‘a tissue [or fabric] of quotations’, weaved from past stories, conversations, and utterances. Gothic texts, however, are particularly patchwork in their construction. Patchwork, after all is both about the repetition of patterns and the recycling of old materials into something new. Gothic patchwork, as is clear from the outlandish story of Otranto, is also about creating startling contrasts and unusual combinations.

The conventions popularised by Otranto have been repeated many times over, and most can be found in the works of the authors featured here today: settings in a dark, barbaric past; the labyrinthine halls of an ancient castle or aristocratic pile, ruins, graveyards, tyrannical villains, uncanny or supernatural events; the found manuscript (be it letter, diary, or historical account), and, not forgetting the return of the dead to haunt the living - in whatever form that may be.

The Gothic is invested in the repetition of such motifs - not because it is a tired formula – a worn out cliché - but because repetition is part of gothic’s patchwork. Each repetition is repetition with a difference, revealing the possibility of something new. Gothic raids the past, but at the same time, continually reconstitutes itself, finding new combinations and patterns.

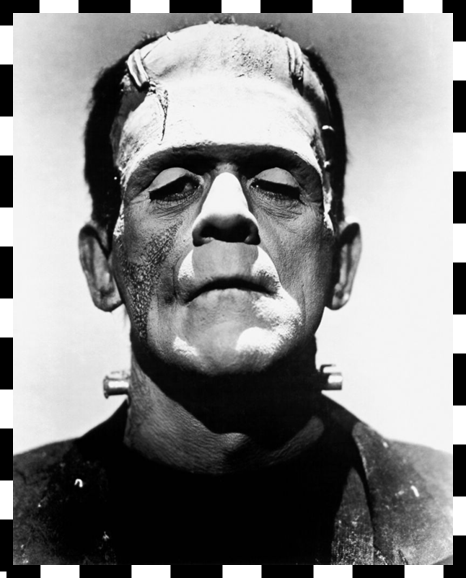

The gothic fictions of Celia Rees and Chris Priestley are particularly interested in gothic’s literary past, with both authors ‘taking on’ canonical novels in their contemporary fictions. Mister Creecher, by Chris Priestley, published in 2011, looks back to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Blood Sinister, by Celia Rees, published in 1996, to Bram Stoker’s Dracula.Both novels represent the patchwork nature of gothic in the way they embrace repetition, and bring together different elements, re-making gothic for a new audience.

Mary Shelley’s 1818 novel, Frankenstein, is itself a reconstitution of gothic. For a start, the expected ruined castles and graveyards appear only at the edges of the text and the obvious tyrannical villain is entirely absent. What Frankenstein does repeat from earlier gothic novels, however, is the idea of framing the story.

The framing device used by Walpole in The Castle of Otranto is fairly simple. In contrast, Frankenstein uses a complex series of frames, with one story embedded inside another. The novel is something of a puzzle box inside which key aspects of the story are repeated from different perspectives. Frankenstein is a collection of different first person narratives, a patchwork of voices, and, woven into its assembled letters, are references to even older works: novels, philosophy texts, the bible and myth. Fred Botting describes it as ‘fragmented, dis-unified, assembled from bit and pieces… rather like the monster itself.’

Inside the patchwork fabric of the novel Frankenstein, the very act of repetition becomes something monstrous. For example, many critics read the novel as a story of psychological doubling seeing Frankenstein and the Monster as a doubled, duplicated and split self, whose confrontation inevitably leads to mutual destruction. In another sense, Victor also duplicates - or repeats - the actions of anti-heroes who have gone before. In Victor’s desire for knowledge and power, for example, we witness the repetition of the tragedies of both Faust and Prometheus.

Repetition and duplication are everywhere in Frankenstein – insidious and destructive. The rejection of the monster by his creator – often read as the rejection of a vulnerable child by a neglectful parent - is repeated time and time again, and, ultimately, is what leads the monster to destroy a child himself – Frankenstein’s infant brother. Later, Frankenstein’s brutal destruction of the female specimen he has built will be repeated by the monster in the violent murder of Elizabeth, Frankenstein’s fiancée. Repetition is also woven into the outer layers of the novel Walton’s letters that open the narrative themselves tell the tale of an act of hubris. Walton desires to reach the pole at any cost, and, in his desire for the forbidden, we see a potential repetition of Victor Frankenstein’s mistakes.

Frankenstein, then, published half a century after Otranto, does repeat some gothic motifs from earlier novels, but uses them to tell a very different story, one in which repetition and duplication are themselves dangerous processes, leading to destruction and disintegration.

Set in 1818, Chris Priestley’s 2011 novel, Mister Creecher, fills a gap in Shelley’s original plot, telling the story of the journey the monster makes when he follows Frankenstein to England. Mister Creecher imagines what happens to the monster in the months before he faces Frankenstein on the remote Scottish island where the scientist has been building the monster a companion. Like the original novel, Mister Creecher is also obsessed with repetition and duplication and its destructive potential, but it weaves this gothic thread into a new configuration.

Whilst Mister Creecher is concerned with characters from Shelley’s novel, its main character – Billy - is from another literary world altogether. Billy – an orphan turned pickpocket – reminds us of the children depicted in Charles Dickens’ novels, notably Oliver Twist. Indeed, Billy’s early life is an echo of Oliver’s. ‘Creecher’ – the monster - steps out of the pages of Shelley’s novel and into the streets of Dickens’ London.

However, Mister Creecher is a patchwork text that goes beyond simply stitching together two different worlds. The novel takes us on a journey from the streets of Dickens’ London to the outskirts of Elizabeth Gaskell’s Manchester and, finally, to the fells of William Wordsworth’s Lake District. Along the way we encounter references to an array of literary and popular fictions: Huckleberry Finn, Great Expectations; Terminator 2; the Hollywood monster movies of the 1930s, in which Frankenstein’s monster was often depicted as a mute, brutish freak; as well as the so-called ‘Newgate’ novels of the Victorian period, which romanticised the life of the criminal and highwayman. And - sprinkled atop - lines from the Romantic poetry of Keats and Shelley.

Among this diverse patchwork, Mister Creecher is, like the original Frankenstein, deeply interested in repetition. Effectively, Mister Creecher duplicates the story told in Shelley’s novel within the world of Oliver Twist. Mister Creecher explores how monsters are created by people and represents Shelley’s monster as an orphaned child who has been denied a loving family. It is the trauma of his neglect that makes him so dangerous. The same is true, of course, for Billy. In Dickens’ literary world, though, the abandoned orphan – most obviously Oliver Twist - is often saved from a life of neglect and manages to find happiness in a surrogate family. By repeating Oliver’s story through Billy, Priestley effectively corrupts and undermines the happy endings often offered by Dickens’ novels. Mister Creecher introduces into Dickens’ world a kind of monstrous contagion, which means that we cannot read Oliver Twist in the same way again.

Like Frankenstein, Mister Creecher is infested with insidious doubling and repetition, but this time they reach beyond the pages of the novel. For example, the murder of Elizabeth – Frankenstein’s fiancée - from the original is duplicated in Mister Creecher in such a way as to create multiple echoes of the event. After Billy’s love, Jane, dies – from a weak heart - he finds her corpse mutilated at the graveside, its heart ripped out and taken – presumably - by Frankenstein to be used in the production of a mate for Creecher. This moment of violence echoes not only the events of the original novel – the destruction of the female mate by Frankenstein and the vengeful murder of Elizabeth by the monster – but also looks forward to the violence to come in Oliver Twist – in particular, the brutal murder of Nancy.

Character roles are doubled twice over in Mister Creecher too. Creecher and Billy are duplicates of one another, both as abandoned sons, orphans and innocents turned monsters and there are multiple fathers. Frankenstein, Creecher and the selfish fence, Gratz, who runs the pickpocket gang, all play the role of exploitative and uncaring father. Ultimately, Creecher repeats his creator’s mistake when he abandons Billy at the end of the novel.

The duplication of characters in Mister Creecher is more than just a collection of references to past stories and tropes. Duplication becomes even more insidious than in the original novel. It becomes a kind of contagion, or infection, with each repetition passing on violence and degradation to another subject. In Shelley’s novel, of course, Walton learns his lesson after hearing Frankenstein’s tale, and, ultimately, turns his ship back from the North Pole. No such lessons are learned in Mister Creecher. Characters simply replace and repeat one another, and violence and destruction are perpetuated.

In its repetition of the monster’s story, Mister Creecher forces us to re-read and reconsider works by both Shelley and Dickens, putting characters from their novels into new contexts and configurations. By the end of Mister Creecher you won’t be able to read either Frankenstein or Oliver Twist without thinking of Billy.

Gothic patchwork repetition, then, can be used to make us reconsider past works and stock characters – to change the way we think about villains and monsters. Celia Rees’ patchwork gothic fiction, however, is uses repetition instead to blur the line between reality and fiction.

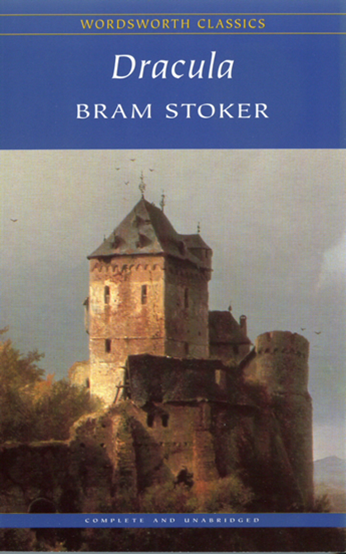

The source text for Rees’ 1996 novel, Blood Sinister, is Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1897.

Published towards the end of the Victorian period, Dracula is further iteration of gothic again from Frankenstein, and its concerns are very different. The Gothic castle, for example, returns to centre stage in the novel’s opening that tells of Jonathan Harker’s incarceration in and escape from Castle Dracula, a terrifying, decaying edifice perched in the Carpathian mountains. In many ways, Dracula actually uses far more gothic trappings than Frankenstein. This is a novel that returns to classic eighteenth century gothic and repeats stock features such as mountains, castles, nuns, graveyards, and ruins. However, just as with Frankenstein, the patchwork way in which these motifs and ideas are reproduced means that Dracula produces something very new, very modern, from old images.

Dracula himself is more than a classic Gothic villain and is certainly more terrifying than Walpole’s Prince Manfred. Dracula is both ancient and modern, no longer chained to a past time, or distant place - Dracula enters the London of 1897 fully equipped to deal with a bustling modern city. Dracula disorientates: he appears as both young and old; he is seemingly limited by his need to sleep in his home soil - and yet appears to be alarmingly mobile - always already everywhere the other characters have been, always one step ahead. Gothic villains have always been liminal figures -simultaneously both and neither one thing nor another, exceeding and crossing boundaries. Yet, in addition to this, Dracula also creates a villain who is un-representable, un-knowable – a dark gap in our knowledge of the world.

Consequently, a kind of hysteria builds up around Dracula, which is reflected in the way the novel is constructed. As Fred Botting explains, the way the novel is formed - made up of letters, journal entries, medical reports and clippings from newspapers – creates ‘a whole whose immensity, like the un-representable horror of Dracula’s unreflecting image, remains obscure.’

In Dracula, there is still a concern with repetition and duplication, but this is now coded into the very fabric of the novel – and, instead of being about monstrosity and violence, it is about knowledge itself.

Everything that we read in the novel has been copied or duplicated at least once from its original source. Jonathan Harker himself notes ‘that in all the mass of material of which the record is composed, there is hardly one authentic document… nothing but a mass of type-writing.’ Everything that the characters know about Count Dracula is contained in documents that are copied, re-ordered, and then copied again. After being sabotaged, the papers are locked away in a safe before being re-copied, added to and somehow, by the end, composed into a whole. One critic – Neil McRobert – has argued that though Dracula is a text obsessed with the accuracy of the knowledge it contains, the fact that it is composed from so many copied fragments actually works to undermine the accuracy, order and knowledge the characters strive for within the story.

Dracula is a story that problematizes truth and authenticity. Like older gothic tales, it is a patchwork of supposedly authentic documents put together to tell an incredibly outlandish tale. Here the documents that compose the novel are supposed to be in themselves a source of authority and truth – a news report, a medical report, legal papers - but in a blurring of science and the supernatural, and a concern about the genuine nature of the documents, knowledge becomes precarious, dangerous and uncertain.

Blood Sinister reworks many of the concerns about knowledge we find in Bram Stoker’s novel. Like Count Dracula, the vampire in Celia Rees’ novel disturbs boundaries and transgresses categories. Count Szekelys is both ancient and yet youthful; a figure from the distant past, at ease in Ellen’s modern world; he is both precariously weak, grievously ill, and yet preternaturally strong and powerful. The Count seems to be everywhere at once – a figure from a tale found in an old diary, but also, simultaneously, at Ellen’s bedside, at her window and outside in the street. Just as Dracula is unrepresentable and has no image in the mirror, this Count too represents the unseeable – we know he has been there, but he leaves no trace.

Like Dracula, Blood Sinister is also interested in the hysteria surrounding the vampire. Duplicating aspects of Bram Stoker’s narrative technique, Blood Sinister explores this hysteria through the layering of its narration. Ellen, the main character, finds a diary belonging to her great grandmother – also named Ellen. The diary slowly reveals the story of the former Ellen’s encounter with a vampire – Count. Modern day Ellen becomes obsessed with the diary, exhausting herself and exacerbating her own illness by refusing to stop reading. At the same time, the Ellen within the pages of the diary becomes more obsessed with the figure of the Count, less rational and sure of herself, and, ultimately, unable to explain the events around her. This hysteria effect is duplicated when modern-day Ellen herself begins to feel hunted and pursued, and the reader begins to fear for her, just as she fears for the girl in the diary.

This layered narration has at its core a supposedly authentic document, a diary telling true events. However, the truth of this document is undermined by the unrepresentable figure of the vampire himself. Like many popular gothic novels, Blood Sinister is structured around a Hermeneutic code – that is – the reader is pulled through the novel by a desire to work out the mystery, find out the truth. In Blood Sinister, however, when we get to the crucial moment – is Ellen’s great-grandmother turned by the vampire? – the diary breaks down. There is a gap.

Blood Sinister, then, is interested in the same problems to do with knowledge as the original novel. And yet, that is not all. For in this new configuration of the vampire tale a very different problem arises. Dracula is composed entirely of first person accounts. In contrast, Blood Sinister weaves the diary text into a third person narrative, causing a disjunct or jarring between the two forms. On the face of it, a first person narration would appear to be more genuine, more authentic, but when framed by a third person narration, the diary form begins to feel artificial. This is because third person narration is a convention we associate with reality even while it actually distances us from the events it narrates. Paradoxically, then, Blood Sinister complicates the problems of authenticity found in Stoker’s novel, by mixing conventions. The ‘real’ events – those in the diary – begin to feel like a story – and the story – that which is narrated – comes to feel real. Further blurring then occurs when the diary entries stop abruptly before we find out the truth.

Again, the gothic motif of doubling makes a reappearance. In Blood Sinister there are two Ellens, and two texts. At first these are distinct and separate, but, as the story tries to reveal the mystery, blurring and disintegration occurs. Diary becomes dream and dream becomes reality. It isn’t enough in the novel for us to read what has happened to Ellen - we have to experience it for ourselves. However, this creates a paradox – for in experiencing Ellen’s story for ourselves we have to leave behind the authenticity of the written document, and enter the world of fantasy, of heightened states and fever dreams. In Blood Sinister, recorded documents become real, but are quickly consumed again back into a fantastical narrative. Lines between reality and fantasy and between truth and story are thus doubly blurred.

Like Mister Creecher, Blood Sinister embodies the way in which Gothic is always a patchwork form. This is a novel not only indebted to Bram Stoker, but to many other vampire fictions that have come along since – cinema in particular. The novel’s dreamlike sequences and descriptions recall cinematic vampire texts of the 1980s and 1990s, further complicating the relationship with the original Stoker novel which is, after all, obsessed with its mass of typewritten pages.

Neither Blood Sinister nor Mister Creecher simply repeat gothic tropes of the past, but instead rework and reconfigure them. It was actually Celia Rees’ later novel, Witch Child, that inspired the title for this presentation. In that novel, the story is a mass of pages literally stitched inside a patchwork quilt. This is a striking image that reminds us that gothic always plays games with the borders between reality and fantasy, history and fiction, the material and the supernatural. As such, it remains a rich mode for contemporary novelists to explore. As Catherine Spooner has explained, gothic is ‘profoundly concerned with its own past, self-referentially dependent on traces of other stories, familiar images, narrative structures, intertextual allusions… cannibalistically consuming the dead body of its own tradition.’

It is the re-appropriation and re-invention of gothic time and time again that make it so ripe for new audiences and interpretations. Again, to quote Catherine, gothic is ‘a crypt of body parts that can be stitched together in myriad different permutations.’

Novels by Priestley and Rees – and others – look backwards to the past – both celebrating great gothic novels but also asking us to reconsider them. Blood Sinister and Mister Creecher use patchwork to supplement the gothic with new fears.

References

Barthes, Roland. 1977. Image, Music, Text Edited and translated by Stephen Heath. (London: Fotana).

Botting, Fred. 1996. Gothic (Oxon: Routledge).

McRobert, Neil. 2012. ‘"This is a wonderful machine, but it is cruelly true."', Conference Paper delivered at Dracula and the Gothic, University of Minho, Portugal.

Spooner, Catherine. 2006. Contemporary Gothic (London: Reaktion).

County College, Lancaster University, LA1 4YD, UK | Tel:+44 (0)1524 592129 Fax: +44 (0) 1524 594247