Conceptualisations of animals, plants and nature |

|

Block 4 |

The Romantic Interlude |

|

|

There is not much agreement about what the Romantic period is - what its dates are, what its characteristics are.

It falls anyway around the end of the 18th Century, and the limits I tend to recognise are set by the Sturm & Drang movement in what was to become Germany from 1770, and 1830

I see it as a reaction to the thrust of scientism in the 18th Century - a pause called in the programme of limitless extension of Newtonian science.

A leading diagnosis of our present condition is that somehow human beings have set themselves apart from nature, and it is this that leads to the dangerous ways we have of exploiting the world about us. Understood properly, human beings are part of nature. If we understood that we would understand that destroying the prairie or exterminating the wolf or polluting the sea are all forms of self-mutilation. Insofar as we are part of Nature our well-being is an aspect of the well-being of Nature as a whole. John Donne's famous lines refer most obviously to the community of human beings to which he is urging we should all remember we belong. But - it is said - there is a wider point to be made. As human beings we are parts not only of the community of humanity but of the community which makes up nature as a whole. "We are all One Life", in the words of Coleridge (quoted in M.H. Abrams, The Mirror and the Lamp, Oxford, 1953, p.65.He is speaking in appreciation of the Hebrew poets - see Salinger in Blake to Byron, p.189). So the bell tolls for us not only when a fellow human being dies but at the destruction of any member of that vastly wider community which is Nature itself.

Web stuff |

|

The rhetoric here, which will be familiar, covers a range of views which differ quite seriously from each other. At one pole the idea that human beings are part of nature is little more than a reminder that 'he who shits on the path will find flies on his return', as the Yoruba proverb has it. In one sense such a reminder might be the most important thing to reiterate and amplify: Be careful! Think of the medium and long term consequences of what you do! It only needs we human beings to adjust our behaviour (including the behaviour of our states and corporations) in the light of that admonition and the human-made threat to our survival would be removed.

At the other pole, the unity that is proposed to embrace in one Nature human beings on the one hand and all that rich variety of things that are usually located in the 'environment' on the other is of a more intellectually challenging character, and it is this that we shall now explore.

|

The most sustained development of the idea that "we are all one life" comes in contemporary philosophy from a school of thought which calls itself 'deep ecology', associated first and foremost with the name of Arne Naess. This school adds to the idea of unity the notion of 'self-expression' as a goal: the unity that is Nature is motivated by a drive towards self-expression.

These concepts are not new, however, and it will I think be helpful to approach them through an earlier movement of thought, namely the discontent, voiced towards the close of the 18th Century with what had become of 'science': the 'romantic' movement.

|

| Arne Naess |

What you have in this movement is an attempt to reject the conception of the world and of the human place in it that had been sponsored (as the Romantics saw it) by the pioneers of Modern science (such as Bacon and Descartes) in the 17th Century and carried through as the 'Enlightenment' into the 18th C. .Part of the benefit to us of exploring Romantic thought is that it gives us the occasion to review the mind-set it was reacting against - the mindset of the Enlightenment. In spite of the best efforts of the Romantics, large elements of the Enlightenment conception are part of our outlook today, and some of the critics of contemporary thought, the proponents of deep ecology for example, may be regarded as renewing the Romantic critique.

The perspective of the Enlightenment was to regard Modern science in its earliest days as having generated an unprecedented increase in knowledge in the fields of mathematics, astronomy and physics, and as having the potential of generating the same kind of revolutionary progress as it was applied elsewhere. The Enlightenment thinkers saw their age as one in which Modern science, having been launched in spectacular fashion by the pioneers, was now advancing towards maturity - advancing through its application to every field where knowledge for human beings was held to be possible. The general attempt to apply science throughout the entire domain of human knowledge is sometimes called the Enlightenment project.

Towards the end of the 18th Century, a reaction set in. It took the form not of the rejection of science, but of the demand that science should reform. It is not clear that it got very far.. It sponsored new concepts that became influential, and science certainly took a turn as the century turned. (Foucault calls the turn a revolution indeed, one that rivalled the birth of Modern science in significance) What is unclear is whether the new direction was one which the Romantics would have welcomed.

What do you think?Are you surprised to find such a strong echo of modern environmental concern and Romantic thought? What developments in the 19th and 20th Centuries would you expect to have had a revisionary influence on environmental thought? |

RepriseI described the outlook of the 18th Century under the following heads:

I see the Romantic thought as a reaction to this. |

|

|

Herder |

The Romantics sought to insist then on a conception which made the human being the originator of activity, and not simply a node in a causal nexus. "Everyone's actions,' says Herder, 'should arise utterly from himself'. (Herder, quoted in Pascal, p. 135; "The great achievement of English Romanticism was its grasp of the principle of creative autonomy" - Northrop Frye, Blake after two centuries, in English Romantic Poets, ed. M.H.Abrams, New York, 1960, Galaxy, p. 65.). If human beings have no power to initiate change they are mere 'playthings' of forces impinging upon them, and to be a plaything, the early Sturm und Drang writer Lenz put it, 'is a dismal, oppressive thought,' amounting to ' an eternal slavery, an artificial .... wretched brutishness.' Instead, we should place the capacity to act at the centre of our conception of the human being: 'action, action, is the soul of the world, not enjoyment, not sentimentality, not ratiocination ... " (Lenz, translated in Roy Pascal The German Sturm und Drang Manchester, 1953, Manchester University Press, p. 1948,9).

[Note: It is usual to recognise a distinction between the German Sturm und Drang movement on the last quarter of the 18th Century and the Romantic movement which many say came after. It is nevertheless arguable that the two belong together.]

A part of this new insistence on the power of human beings to initiate change amounted to a new view of the nature of the human mind. The mind had been a billiard table on which ideas cannoned about: the revolutionary view was that the mind took initiatives.

|

| Coleridge |

The poet Coleridge - the Coleridge we know as a poet, anyway, though he also thought of himself as a philosopher - articulated his distinction between fancy and imagination as a way of making the point. The fancy is little more than a spectator in the theatre of the mind, whereas the imagination, as Coleridge conceives of it, is 'a living Power', creating new forms. Discrete ideas, simply observed by the fancy, or linked loosely together in temporary assemblies, are by the imagination, as Coleridge understands it, melted and cast anew. The imagination is vital - he asserts, meaning that it had that power, often associated with things that were alive, to initiate change.

The creative power that is the imagination is central to the human mind, says Coleridge. It is the

Immanual Kant, from whom Coleridge derived much his (philosophical) inspiration, broke with Enlightenment thought on this point too: the mind was no mere spectator: it played a part in creating the world as we know it.

|

Lenz (a member of the Sturm und Drang movement) in his paper On the Nature of our Mind argued that the difficulty we feel in our minds when we attempt to acknowledge that our 'decisions' are determined is a hint that they are not - a hint that instead there is within us a fount of action which is to an extent independent: 'What then, I only a plaything of circumstance? I ---? Whence comes the conviction that 'you did that, you were the cause of that, not nature or the impact of alien forces ' ... Might it not be a hint given by nature to the human soul, that the soul is a substance, though not born independent, but with a movement, an instinct within, to work its way up to independence; to separate itself out, as it were, from this great mass of intertwined creation and to establish itself as a being existing for itself ...' Lenz, quoted and translated by Pascal, ibid. p. 126. |

Compare Leibniz, from whom it is known Goethe drew inspiration: 'We may give the name entelechies to all created simple substances or monads. For they have in themselves a certain perfection; there is a self-sufficiency in them which makes them the sources of their internal actions - incorporeal automata, if I may so put it.' (Leibniz, Monadology, translated by Mary Morris, (London: Dent, 1934), p.6 (§18)

What do you think?What do you think of the Romantic idea that in the poet human kind achieves its highest expression? |

This is an extra point, beyond the basic one that the mind becomes thought of as active:

Linked with Wordsworth's articulation of a new attitude towards nature is his attempt to articulate the inner workings of his mind.

The Prelude is subtitled "The growth of a poet's mind".

It represents the first attempt by a poet "to examine the human mind

from a psychological viewpoint. What he tries to describe, as his subtitle

to the poem suggest, is the workings of the subconscious mind." Trying

to show, for one thing, "the way that certain events, although unrecognised

at the time, connect and link themselves together and gradually build themselves

up into a man's inner self"

(Drabble, Wordsworth, p.81,2)

Drabble points out that in a way Wordsworth's point is made by the 18th Century philosopher Hartley (1705 57): that our moral character is not innate but grows in childhood and youth, but that where Hartley's conception had been rigorously mechanical, Wordsworth's is more complex and subtle, anticipating psychoanalytical ideas rather than echoing earlier ones. (Drabble, Ibid p. 83)

What do you think?Can you imagine thinking of the mind without thinking of there being an 'unconscious'? |

Romantic thinkers had an alternative to put in place of the conception of the human being as a cloud of jostling particles. They proposed instead the metaphor of the seed and its development into a mature plant.

This metaphor encapsulated a quite radical innovation. It gave a way of thinking of the human being as in origin inchoate, or lacking form, but as then gradually acquiring structure and differentiation as development towards maturity proceeds. This understanding was applicable to physical development, but the Romantics also applied it to the development of the person as a whole. They recommended understanding the person as something which began unformed, and as something that acquired form as time passed.

|

This way of thinking of development relied on the idea of a potential becoming realized. In the beginning, the fertilised egg was small and ndifferentiated. Eventually it grew into something with elaborate differentiation and organisation. Development towards maturity could be regarded as the gradual realisation of that original potential. This was how the Romantics saw the life of the person as a whole, too: a movement towards the realisation of potential. They saw it as a process of self-realization, a process which begins with a real but inchoate self, and proceeds through the gradual crystallisation of characteristics and personality which had been 'pointed to' - but only 'pointed to' - in the beginning. Self-realisation, for the Romantics, was the point of life.

The new 'Romantic' conception of the self, taking shape here, is thus of a potential which undergoes development. Already I have pointed out the importance the Romantics placed on the power of the human being to initiate change. The new self is also characteristically self-powered. The drive to development comes from within. In the mind, Herder says, 'there glow forces, living sparks'. (Quoted by Pascal, ibid., p.183.) It is these inherent, autonomous, self-energising 'forces' pushing their way against the world outside that propel the self into realisation. As Charles Taylor puts it, for Herder, realising the human self involves 'an inner force imposing itself on external reality'. (Taylor, Hegel, Cambridge, 1975, p.15)

The Romantic self therefore in its primal state is a kind of seed: it was thought of as destined for development, a process which it would launch under its own initiative, as it were.

We have here in fact a pioneering expression of a major conceptual shift, one which Foucault identifies as marking the transition between what he sees as the 18th Century and 19th Century frameworks. For the idea of a thing defined in terms of its potential and its intrinsic power to drive the potential towards realisation - of which the concepts of the seed and the self are both examples - is taking shape here for the first time.

| Here is the Herderian conception of the self coming through in a more recent writer: 'Educational efforts must, it would seem, be limited to securing for everyone the conditions under which individuality is most completely developed - that is to enabling him to make his original contribution to the variegated whole of human life as full and as truly characteristic as his nature permits ...' Percy Nunn, Education: its data and first principles, 3rd edition, E Arnold, 1945, pp 12-13. |

The Herderian theme of a potential and its realisation was taken up by another central figure in the reaction against

Enlightenment science, Goethe. Goethe applied it in the development of his concept of the 'archetype'. An individual plant, for example, for Goethe was the expression of a something that was there from its beginning, a something that pointed to a mature form, and which drove the plant to grow towards that goal. This 'something', a potential and an impetus towards the realisation of it, was his 'archetype'.

The principles of the seed-self were put to use again and again by Romantic thinkers.

Nature 'herself' was thought of after such a manner. For Schelling (the philosophical parent of the Naturphilosophen - Coleman ) 'nature becomes a creative spirit whose aspiration is ever fuller and more complete self-realization.' Blackburn's Dictionary, p.332.

It was the self-realization not of the individual nor of nature but of a society or nation - or culture - that Hegel placed at the heart of his understanding of the human condition, the expression of the Geist. Whereas the 18th Century has thought of society as the aggregate of the individuals that belonged to it, for Hegel the individuals and their activities were the expression of something underlying. Once again we have the Romantic teleological leitmotif of something that is best described as a 'potential' and its self-powered progress towards realization.

| Introduction to Froebel and the kindergarten |

Froebel articulates the basic Romantic nostrum: 'It is the destiny and life-work of all things to unfold their essence ...' (The Education of Man, trans. W.N. Hailmann, D. Appleton, 1887. p. 2)

What do you think?What things do we think of today as having an inner core which gradually expresses itself over time? |

I have explained Taylor's thesis that Herder and the Romantics created a new conceptualisation of the human being, one that placed the gradual realisation of an original potential centre stage.

The 'destiny and life-work of all things' very much including human beings, is ' to unfold their essence ...'

said Froebel, parent of the kindergarten concept. (Froebel, The Education of Man, first published in 1826, trans. W.N. Hailmann, D. Appleton, 1887. p. 2.)

Partly to get this new idea in focus, I now want to try and explain what happened to this idea in the subsequent period. (Taylor rather suggests that this Herderian idea simply comes through to us in the present day, if with other strands woven around it.)

My claim will be that the notion of an original potential gives way to the idea of a person, through educative experience, coming to possess a 'character', which is their moral core.

This new way of thinking about a human being is reflected in the writings of the theorists of the 19th Century public school, notably Arnold.

Before saying more about the 19th Century concept, let me give a little more articulation to Romantic thought.

Here is Johann Friedrich Herbart (1776-1841) insisting, against the 18th Century, that moral education should be concerned not with rule-guided habits of behaviour but with a development of something behind overt activity, namely what one might call a 'quality of mind':

The new self must have 'insight', he claims:

Johann Friedrich Herbart, The Science of Education, trans. H.M. and

E Felkin, Swan Sonnnenschein, 1904.

Quoted in the Cohen and Garner volume, p.20.

And here is the same author explaining the new 19th C pilot conception:

"Human nature, which appears to be suited for the most diverse conditions, is of so general a character that its special determination and development is entirely left to the race. The ship constructed and arranged with highest art, that it may be able to adapt itself to every change of wind and wave, only awaits the steersman to direct it to its goal, and guide its voyages according to circumstances."

Johann Friedrich Herbart, The Science of Education, trans. H.M. and E Felkin,

Swan Sonnnenschein, 1904.

Quoted in the Cohen and Garner volume, p.20.

One site where you have the notion of 'character' on the move is the novels of Jane Austen. Her work can be contrasted with the Gothic novels, which she undoubtedly had in her background, but there is also a contrast with the picaresque Peregrine Pickle and its ilk. In the picaresque novel we have a cavalcade of jaunty japes recounted. People as described as having characters of course, but the character is a pattern of behaviour, a set of habits.

Jane Austen articulates

the idea that in a young person - Elizabeth Bennet or Emma Woodhouse - there

is something behind the day-to-day actions and the patterns they belong to.

This something moreover, as the events of the novel develop, is under formation.

Jane Austen articulates

the idea that in a young person - Elizabeth Bennet or Emma Woodhouse - there

is something behind the day-to-day actions and the patterns they belong to.

This something moreover, as the events of the novel develop, is under formation.

D'Arcy in Pride and Prejudice was at first judged (by Elizabeth) on appearances. But she later came to see that appearances gave a false impression. It is a development that has two aspects. The first is that Elizabeth is misled by appearances: there is something to be misled about. And secondly, as Elizabeth comes to realize her mistake she herself is growing up.

Can we say any more about the kind of thing that the heroine begins by getting wrong?

| Excellent hypertext edition of Pride and Prejudice Courtesy Republic of Pemberley |

She has Elizabeth think that it is D'Arcy's 'dispositions and talents': which, truly understood, make D'Arcy the most appropriate partner for her.

'She began now to comprehend that he was exactly the man who, in disposition and talents, would most suit her. …'

(Pride and Prejudice, Chapter 50, or Penguin 1992 Edition, Harmondsworth, p.325)

Tanner writes:

"Just what constitutes a person's 'real character' is one of the concerns of the book: the phrase occurs more than once, usually with the added idea that it is something that can be 'exposed' (and thus, by the same token, concealed). In particular, D'arcy in his letter writes that whatever Elizabeth may feel about Wickham it 'shall not prevent me from unfolding his real character', just as later in the letter he narrates Wickham's attempt to seduce Georgiana, 'a circumstance. ..which no obligation less than the present should induce me to unfold to any human being'. "

Tanner's Introduction to the Penguin Pride and Prejudice, Harmondsworth, 1972, p. 18,19..

There is room of course in 18th Century thought to think of being misled by appearances. There is plenty of dissembling in the picaresque tradition of Smollet et al. Hypocrisy is the great theme of 18th Century theatre. (Sheridan's School for Scandal, 1777). But how was hypocrisy understood? Basically as a species of lying. You said one thing and did another. Or you did two things which were inconsistent. There is nothing here of an underlying reality failing to be discovered or being misrepresented in appearance.

Austen creates the necessary conceptual space by speaking of the possibility of allowing her characters make mistakes. See Tanner's Introduction to the Penguin Pride and Prejudice, Harmondsworth, 1972, p. 4.

We can find in Austen then the new Romantic conception of character as an unfolding potential. But there is a hint of something more, because she entertains the idea of character being mouldable in different ways.

This is the idea that takes over as the 19th Century moves forward. Character is something engineered, not given.

|

|

Rugby School, courtesy the Rugby

School site A note on Thomas Arnold from the Rugby School site |

The English Public School was turned into a building site for this purpose. In the 18th Century, as testified by Gibbon for example, these institutions facilitated 'networking' among the wealthy and taught Latin and Greek. In the 19th Century the mission declared by their reformers was to build character. For it is character that is built on the playing fields of Eton.

And it is character that is at fault should the colonial administrator hoists the white flag when the natives get restless, instead of straightening up his backbone and stiffening the upper lip.

Let me try and bring out the contrast between 18th and 19th Century conceptions of the self in terms of an analogy.

An aircraft may or may not have an engine. If it doesn't it's a glider. Both types of aircraft can be got to move forward. But in one case this is down to one thing, sitting inside the plane, its engine; while in the other, there is nothing inside the plane which thrusts it forward. The whole design of the aircraft appropriates some of the energy of the movement of air outside and exploits it to produce forward movement in the plane.

Are we powered aircraft or gliders? Do have a central power, or is what we have a structure, as it were, which simply draws on the potential in our environment to secure our ends?

This analogy is dangerously suggestive, and I don't want to sponsor much of what it suggests. I just use it to give a clear picture of the contrast I want to make between the idea of the self as a homunculus, and the idea of the self being a configuration of character-traits. I want to make this clear, because my thesis is that the 18th Century thought of the self as the set of character traits, and the 19th Century thought of it as an homunculus.

Features of a person's 'character' in this sense include:

Although this contrasts with the Romantic idea of the self gradually expressing itself, it is clear how one idea builds on the other. In both cases there is something at the core of a person. For the Romantics the entity is a potential that has to take shape through growth. For the 19th Century, the core is something that has to be built. But the notion of there being a core is there in both.

This is already adumbrated by Kant:

'Our ultimate aim is the formation of character.' Kant, Education, Ann Arbor edition, Michigan, 1960, University of Michigan Press, Section 94, p. 98,9.

Kant clarifies what he means by 'character' when he explains that what is 'character' in a good person is obstinacy in a wicked one, explaining

'Character consists in the firm purpose to accomplish something, and then also in the actual accomplishing of it ... For instance, if a man makes a promise, he must keep it, however inconvenient it may be to himself.'

Kant, Education, Ann Arbor edition, Michigan, 1960, University of Michigan Press, Section 94, p. 98,9.

That is, a person with 'character' when facing a challenge, refrains from displaying emotion and refuses to be distracted form their intended course of action.

- strong but vulnerable to catastrophic loss of integrity the moment a fault develops.

You get this most powerfully put in Conrad's story Lord Jim (though

as late as 1900). Jim had a moment of failure, when he quit the ship when his

'duty' dictated that he should stay. Conrad's theme is that this revealed a

permanent truth about Jim's character, that it was flawed. It was not to be

seen as a momentary failure to catch the rising current, but as the engine failing.

The Romantic movement challenged in this way the idea that the human mind was passive. But nature too, for the Enlightenment, had been passive, and furnished with entities that were passive. Romanticism challenged this also.

The concept it reached for in asserting its alternative view was the concept of life. Living things have always suggested the idea of spontaneity. Animals of course have no appearance of being passive. They were characterised by the Greeks as things possessing the power of movement - animal souls, belonging to entities with with the capacity to respond to stimulation. But plants have something of the same apparent power too. They don't generally move about, but they do spring up out of seeds in a way that has always been recognised as distinctive and highly significant. So the Romantics expressed their opposition to the prevailing deterministic view of the natural world by insisting that it was alive.

By implication, the insistence that things in nature and everything belonging to it were 'alive' militated against the reductionist nostrums of established science. There were also plenty of explicit statements to this effect. Goethe (not classed by historians as a Romantic, but belonging to the late 18th Century and a powerful critic of Enlightenment science) conducted an investigation into the nature of colour, and the human experience of colour, because he thought the reductionist treatment offered by Newton profoundly misconceived. More well known are the pronouncements of the later Romantic poets, such as Wordsworth, with a vision of nature as anything but the endless jostling of colourless, odourless, tasteless, mindless particles:

"Ye Presences of Nature, in the sky

Or on the earth! Ye Visions of the hills!

And Souls of lonely places!"

(The Prelude 1, 490 4, 499 501)

Nature is a cathedral of Presences, for Wordsworth, not a matrix of particles, as this famous invocation makes clear.

Goethe saw nature as an agent too: 'Nature! ... She lives in countless children, and the mother - where is she? She is the sole artist, creating extreme contrast out of the simplest material, the greatest perfection seemingly without effort, the most definite clarity always veiled with a touch of softness. Each of her works has its own being, each of her phenomena its separate idea, yet all create a single whole.' Goethe [sic], 'Nature' (ascribed to Tobler, 1783) in Scientific Studies, p. 3. |

What do you think?How do we understand life, or 'being a living thing', today? Is our understanding significantly different from the Romantics'? |

Romanticism

gives a new authority to feeling

Romanticism

gives a new authority to feelingWe also have highlighted by Wordsworth the new significance attached by Romanticism to feeling. The Presences he has registered in the passage just quoted invest, he says, the whole natural world with feeling. He thinks of the way in which the wind imparts a swell to the ocean, and explains that that is how we are to understand the workings of the 'Presences': they make

(The Prelude 1, 490 4, 499 501)

|

| Novalis courtesy International NOVALIS Gesellschaft |

Nature and natural things were in this way thought of by the Romantics (or at least by the Wordsworthians) as capable of supporting 'feeling', but also a new perspective was taken towards the feeling that went on in human beings. As I have pointed out, feeling had not been neglected by Enlightenment science: it had been regarded as an important part of the human machine. But for the Romantics it had an altogether different significance. They looked upon feeling rather as a much earlier tradition had looked upon reason: it was our guide to right behaviour.

'The heart' as the poet and writer Novalis puts it,

(Cited by Taylor, Sources of the Self, p. 371.)

There was a long tradition before the 18th Century and before modern science which thought of the experiences we now identify as emotions of one kind or another as distracting or misleading. Plato suggests the picture of the soul of a person split into parts, with reasoning often in conflict with desiring. Our reason might tell us to do one thing, while our desires tell us not to. For example, our reason might tell us the water is poisoned, but our desire to drink might drive us to swallow the poison nevertheless (MacIntyre, A Short History of Ethics, p. 39).

In medieval thought you have the idea that it was the role of reason to tell you what you ought to do, and that a weak person, even knowing what s/he ought to do, might be preyed upon by anger, or fear, or envy, or whatever and stopped from acting as s/he knew s/he ought. Medieval thought had the reason as the compass of a person's ship. It showed the way, from which however the storms of 'feeling' might mislead.

In re-evaluating the role of feeling in human life the Romantics had more than Enlightenment rationality to oppose therefore. The condemnation of feeling went back a long way, and had taken a variety of different forms.

What do you think?What authority do we accord feeling today? |

|

"[William Cowper, the 18th Century poet] makes a sketch of the object before him, and there he leaves it. Wordsworth, on the contrary, is not satisfied unless he describe not only the bare inanimate outward object which others see, but likewise the reflected high-wrought feelings which that object excites in a brooding self-conscious mind. His subject was not so much nature, as nature reflected by Wordsworth." Bagehot, article first published in National Review July 1855, reprinted in Cowper - Poetry and Prose, ed. H.S. Milford, Oxford, 1930, Clarendon. |

Feelings were important for the Romantics partly because they thought of them as the way in which Nature manifests itself to us. In heeding our feelings therefore we are heeding the promptings of Nature. The early revolutionary Herder did most to articulate this conception, but it is there in William Blake. It is also, famously, in Wordsworth:

See Taylor, Sources of the Self, Ch.21.

|

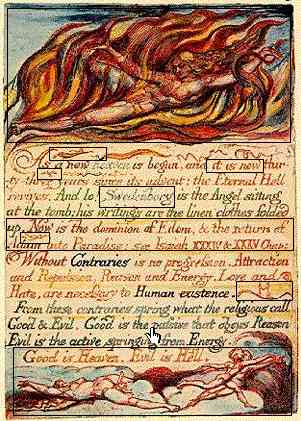

| Blake, The Ancient of Days. Scan by Mike Harden |

There is finally in Romantic thought a powerful strain of 'nature-mysticism'.

There is a long tradition of 'mystical' thought in the West. It lends itself particularly to the strain in Christianity which despises this world and tries to shift the focus elsewhere. An analysis within the Christian tradition describes the mystical experience as one which involves a feeling of awe, of being utterly overpowered, of energy or urgency, of 'stupor' and finally a feeling of 'fascination'. (Otto, The Idea of the Holy)

But other traditions appear to recognise much the same kind of phenomenon. The characteristics that are claimed to be common ground for a number of religious traditions have been listed like this:

Here is a version of the religious perspective, for example:

"As a lump of salt thrown into water melts away . . . even so, 0 Maitreyi, the individual soul, dissolved, is the Eternal - pure consciousness, infinite, transcendent. Individuality arises by the identification of the Self, through ignorance, with the elements; and with the disappearance of consciousness of the many, in divine illumination, it disappears."

From the Brihadaranayaka Upanishad, Stace, p. 118. (The Upanishads , ed cited by Stace, p.88.)

What do you think?Do you think of mystical experience as a window onto reality? |

|

And, more tersely, from the Christian tradition, in a thought which encompasses the whole of Nature as well as the individual soul, Meister Eckhart: "All that a man has here externally in multiplicity is intrinsically One. Here all blades of grass, wood, and stone, all things are One. This is the deepest depth." (quoted by Stace, Mysticism and Philosophy, p. 63) The loss of personal identity, or, put another way, the identification of the self with Nature as a whole, explicit in this mot from Eckhart, is the thought that finds particular expression in nature mysticism. The religious mystic comes to understand that they and God are one. the nature mystic that they and Nature are one. The identity of the nature-mystic expands as it were into nature, so that what is asserted is that the distinction between the individual and nature is lost. the two become one (or what is discovered is that what appeared to be two are have really been one all along). |

Identify something in the Modern world, preferably the Romantic world, which is illuminated by the concept of the internal origination of change.

E.g. health?

Credits

Jane Austen silhouette courtesy Jane Austin Information Page

Arne Naess photo courtesy Sigmen Hendriks

My own materials in the above are for the free use of anybody, except for making money