138 THE STONES OF VENICE CONSTRUCTION

upon him out of the cornice; but would prefer inventing a capital for the shaft itself, without reference to the cornice at all. We will do so then; though we shall come to the same result.

The shaft, it will be remembered, has to sustain the same weight as the long piece of wall which was concentrated into the shaft; it is enabled to do this both by its better form and better knit materials: and it can carry a greater weight than the space at the top of it is adapted to receive. The first point, therefore, is to expand

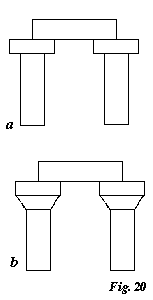

§ 6. Now the entire treatment of the capital depends simply on the manner in which this bell stone is prepared for fitting the shaft below and the abacus above. Placed as at a, in Fig. 19, it gives us the simplest of possible forms; with the spurs added, as at b, it gives the germ of the richest and most elaborate forms: but there are two modes of treatment more dexterous than the one, and less elaborate than the other, which are of the highest possible importance,-modes in which the bell is brought to its proper form by truncation.

§ 7. Let d and f, Fig. 19, be two bell stones; d is part of a cone (a sugar-loaf upside down, with its point cut off); f part of a four-sided pyramid. Then, assuming the abacus to be

[Version 0.04: March 2008]