I. ARCHITECTURE 25

the most beautiful form in which a window or door-head can be built. Not the most beautiful because it is the strongest; but most beautiful, because its form is one of those which, as we know by its frequent occurrence in the work of Nature around us, has been appointed by the Deity to be an everlasting source of pleasure to the human mind.

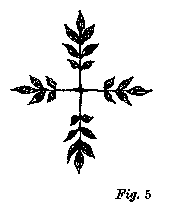

Gather a branch from any of the trees or flowers to which the earth owes its principal beauty. You will find that every one of its leaves is terminated, more or less, in the form of the pointed arch; and to that form owes its grace and character. I will take, for instance, a spray of the tree which so gracefully adorns your Scottish glens and crags-there is no lovelier in the world-the common ash.1 Here is a sketch of the clusters of leaves which form the extremity of one of its young shoots (fig. 4); and, by the way, it will furnish

* Sometimes of six; that is to say, they spring in pairs; only the two uppermost pairs, sometimes the three uppermost, spring so close together as to appear one cluster.

1 [For a more detailed study of the ash leaf, see Modern Painters, vol. v. pt. vi. ch. iv. § 5.]

2 [For a note collecting some of Ruskin’s many references to political equality, see Vol. XI. p. 260. The references to the principle, in nature and in art, of diversity in symmetry, are yet more numerous: see General Index, s. “Symmetry.”]

[Version 0.04: March 2008]