ADDRESSES ON DECORATIVE COLOUR 495

as the man. The stags appeared as if waiting to be shot, their horns looking so much like the branches of the trees under which they stood, that it was scarcely possible to distinguish one from the other. There was not a line in the whole composition that was not false, and yet this was a correct copy of one of the most celebrated works of Claude Lorraine, a drawing in the possession of the Duke of Devonshire.1

21. Mr. Ruskin then exhibited a Parisian MS. of the time of St. Louis, which he said was one of the best specimens in his possession. It was full of animals, figures, and ornaments. He particularly pointed out a white bird, too small to be appreciated without the aid of a glass, but of which he exhibited an enlarged copy, calling attention to the humorous expression of self-satisfaction in the bird’s eye, the ease of its position, and other merits. The whole MS., he observed, was full of figures equally ingenious, and equally beautiful.

22. In many of the examples

23. That was one thing to which outline drawing might be applied. Another was the grotesque. It was not mere humour that was expressed in a grotesque. A grotesque was often the expression of truths in a small compass. The grotesque was as available in poetry as in painting. The poet and the painter, be it remembered, were essentially the same. He

at Brantwood. Mr. Thompson has identified the place of origin at Beaupré near Brussels. Ruskin refers to the MS. at some length in The Pleasures of England, § 99, where a facsimile of a page from it is given in this edition.]

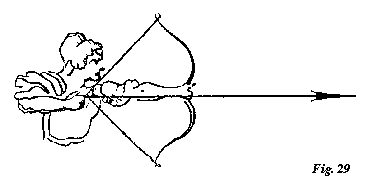

1 [The diagrams here mentioned have been found at Brantwood, and reduced reproductions of them are here given. The Claude is from No. 180 in the Liber Veritatis (“Landscape with Ćneas shooting.”) It is given with more detail, and is analysed, in Modern Painters, vol. iii. ch. xviii. § 26 and fig. 7.]

2 [For Ruskin elsewhere on Hogarth, see Lectures on Architecture and Painting, § 130, above, p. 153; Seven Lamps (Vol. VIII. p. 212); Stones of Venice, vol. ii. (Vol. X. p. 223); Inaugural Address at the Cambridge School of Art, § 22.]

[Version 0.04: March 2008]