Ruskin said 'the sky is for all; … and yet we never make it a subject of thought'. His drawings and paintings of the sky bridged new scientific understanding of the flux of atmospheric elements, and new forms of experimental image-making.

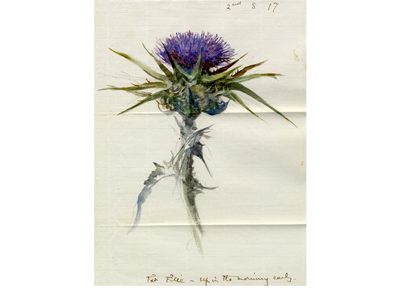

Ruskin’s first love was the natural world, and it was through his writing on ‘truth to nature’ that he turned to art criticism. The project that became the five volumes of Modern Painters began as a defence of the landscape artist J. M. W. Turner, ‘the father of modern art’.

Ruskin describes Turner’s trailblazing skies: ‘It is a painting of the air, something into which you can see, through the parts which are near you, into those which are far off; something which has no surface, and through which we can plunge far and farther, and without stay or end, into the profundity of space’.

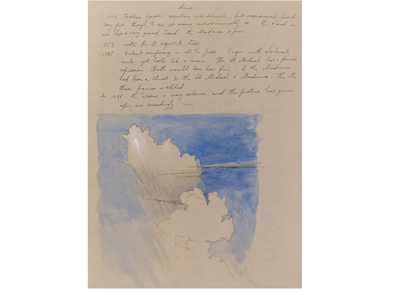

Ruskin wrote, 'Attention to the real form of clouds, and careful drawing of effects of mist… becomes a subject of science with us; and the faithful representation of that appearance is made of primal importance, under the name of aerial perspective'.

Ruskin’s technical drawings illustrate his precision skills as a draughtsman and scientific thinker. For Ruskin, gradations of line as well as colour were central to the delineation of the skies. His ‘Cloud Perspective’ studies from Modern Painters show geometric compositional rulings applied to cloud formations.

Clouds also offered a model of a permanently changing natural world. Ruskin argued that the power of drawing to understand the clouds ‘alters and renders clear our whole conception of the architecture of the sky’.

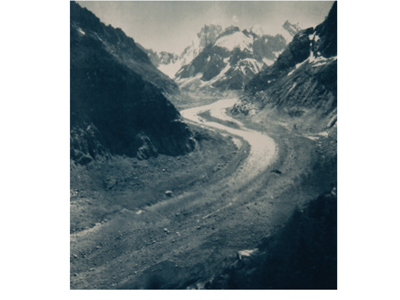

Ruskin painted the skies using a cyanometer, a device for measuring the blueness of the sky. It was invented by Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, who wanted to trace colour intensity of the sky over Mont Blanc. In 1787, Saussure reached the summit and measured the sky: 39 degrees blue. #COP26