|

Contents |

One leading commentator says you could easily think of Aristotle as a supercilious prig. (Alasdair MacIntyre A Short History of Ethics, London, 1966, Routledge, p.66)

Even so, in these two lectures I need to explore a little with you Aristotle's contribution to ethics. Because, prig or not, supercilious or not, nobody has been more influential.

He has been influential partly because he is ambiguous, is capable of many readings. For example, he is claimed today as the progenitor of a contemporary approach to ethics, and one that is fashionable, called 'Virtue Ethics'. I will return to this tomorrow.

But I like him because of the way he sometimes looks at human beings as animals, and tries to think of ethics from that point of view. That is what I will be trying to explain today.

ARISTOTLE (384-322 BC) Born in Stagira, in Northern Greece. His mother had independent means, his father was physician to the King of Macedon. In 367 he moved to Athens and Plato's Academy. Some time after Plato's death, he became tutor to the young Alexander the Great. Later he returned to Athens to found his own school of philosophy.

|

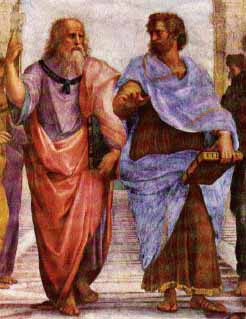

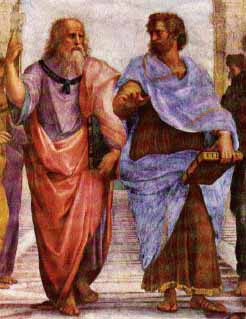

| Plato and Aristotle, detail from Raphael's The School of Athens, Courtesy the Vatican and Berkeley History site |

Aristotle purports to set out for us how we should live.

I suppose this is consistent with his being a prig. But it is also what a lot of people think philosophy should be providing. Not logic chopping, not playing with bizarre ideas which bear very little relation to the world we have to live in, but offering wisdom, serious, considered, guidance on what life is all about and how we should deal with it.

Nevertheless, when we read his answer to this question - the most important question of all, you might think - we are likely to be disappointed.

What he seems to do is to look to the way of life of those around him - to people of the same position in society and life style - and advocate that! That is how to live. And when he lays stress on the life of contemplation, the life of the thinker or the philosopher, he almost seems to be saying: look at me! I am your model. This is the ideal life for the human being.

Aristotle is a sort of 'gentleman' in the context of Greek society. And he accepts as unquestionable the norms of behaviour of the 'gentleman' in Ancient Greece. A gentleman is supposed to behave in certain ways, and Aristotle doesn't criticize these. His approach rather is to accept this pattern and its associated list of virtues as the norm, and to use them as the basis for theorizing.

Web stuff

|

These are the leading virtues that Aristotle sees as defining the life seen as appropriate for the high-born Greek citizen:

PROMPT

How would your own list of virtues begin? Don't bother about understanding what these terms mean. In the terms that come naturally to you, what would you put on your list of virtues?

The discussion site would be interested.

So far, not so good. What I have said of Aristotle's approach makes it sound hopelessly class and culture-bound. Does Aristotle have anything more transcendent to teach us?

I suggest you treat what he has to offer to us as presents in a lucky dip.

There are a number of different points. We should treat these separately on their merits. As a second stage we might consider how they might be seen as implications of a single ethical theory or perspective.

The different points are these:

1. The good for human beings is what enables them to fulfil the way of life that is natural to them. There is a way of life that is natural to human beings.

2. This is done by practising the virtues - the good life is the life in which one practises virtue.

3. Their natural way of life is one in which they exercise reason.

4. Human beings flourish best when they follow the life of contemplation.

5. The doctrine of the mean. 6. We should think in terms of virtues rather than principles.

If you ask what is the good life for a particular animal or plant the answer does not seem terribly obscure. Think of a rhododendron. The label when you buy a new one from the garden centre will give you a list of the things you should do to make sure your new plant flourishes. It needs acid soil, some shade, shelter from wind, protection from frost, mulching, ericaceous fertilizer twice a year.

Provide these things and if the advice is right this particular species will flourish. It will put on growth each year, show healthy-looking foliage, flower in May, enjoy the life span of the species.

So on the one hand with a rhododendron there is a form and pattern of life and a life span that is characteristic of the species, and a list of things you can do which help a particular specimen reach this characteristic pattern. So you have a conception here, in the case of a plant, of its good, and of what is good for it. What is good for it is whatever helps it attain the pattern of life that is characteristic of the species it belongs to.

Can the same sort of analysis be applied to an animal?

Take a frog. It needs water, Spring to come on cue, partners to enjoy, flies to eat. In what sense of 'need'? It needs these things in order to live the life that is characteristic of the frog. A frog wouldn't necessarily die if it lacked say friends in February. But it wouldn't be able to make tadpoles. The full characteristic life of the frog would not be open to it. That is the sense in which it 'needs' company. Do you agree that there is a coherent sense of 'need' here? Does it make sense to say the frog 'needs' partners, even though it wouldn't actually die without them?

Is the sense in which the Rhododendron 'needs' a good frost-sheltered spot, even though it would actually die if more exposed - just lose its blossoms and look stunted and perhaps bedraggled.

One objection to factory farming is that it doesn't give the creatures what they need in order to live the life that is characteristic of their species. If you cage a chicken tightly, and make it stand on wire mesh and cut off its beak, it doesn't actually die - perhaps surprisingly. But it doesn't live the life that is characteristic of the chicken. We say it doesn't live the life that is ''natural' for a chicken.

There is another objection, of course, which is that this treatment makes the chicken suffer. That is true, I think, but put that on one side. Is there another objection, namely that you are stopping the chicken from following a style of living that is natural to it?

PROMPT

What do you think? Concentrate if you can simply on the objection that factory farming methods are 'unnatural' (leaving the question of suffering on one side). Is this objection valid?

The discussion site would like to hear your arguments

-

for the human being

-

for the human beingThe crunch as far as human beings are concerned is this of course: is there a characteristic pattern of life for the human being? If so, what is good for the human being is whatever helps him or her follow that pattern. Think of the rhododendron, the frog, the chicken. Is there something for human beings corresponding to the good for these things?

If so, what is the pattern of life that is characteristic of Homo Sapiens? If we can identify this we shall know what is good for human beings. What is good for them will be whatever helps them live the life that is characteristic of the species... ["The function of man [sic] [is] a certain kind of life" NE, Bk I, $7.]

Aristotle answers this by invoking a line of argument that seems flawed. He asks what it is that is distinctive of human beings. Whatever it is that distinguishes the human being from other species will be the thing that defines what is their characteristic pattern of life.

Can we make this plausible? Probably not, but let's try it.

Suppose we found that only human beings could breath successfully in fumes of sulphuric acid. This would be a distinctive mark, but would it tell us anything about the style of life that was characteristic of the species? Would it tell us what was good for the species?

In itself surely not. But if when we studied human beings breathing acid fumes played a large part in many of their lives, we would conclude that this feature would have to be taken account of when giving an account of the pattern of life characteristic of the species.

|

| Aristotle's Statue at Stagira, Greece* Courtesy Cynthia Freeland |

What Aristotle says is that what is distinctive of the human being is: rationality, or reason. We had better interpret him as saying that the exercise of reason plays a key role in the pattern of life that is characteristic of the human being. Then we can reach the conclusion that allowing ourselves and others to exercise our powers of reasoning is an important good for us.

At any rate, as Aristotle looks at the life of the conventional Greek gentleman, he sees that what is characteristic is the life of the mind - as we might say. This is what he takes to be the characteristic pattern of life for Homo Sapiens - the life of contemplation as he calls it.

Aristotle's theory of ethics: Session 2

In the first part of today we are looking for more nuggets in Aristotle and what he says about how we should live, what happiness is and whether it is within everyone's grasp.

In the second part you are going to indulge me by allowing me to show you a loud piece of film.

The key thing so far is this line of argument from Aristotle.

· The good for human beings is what enables them to fulfil a way of life that is natural to them.

· What is natural to the human being?

· The life in which 'reason' plays the main role.

· (Reason is what is distinctive about the human being)

You remember I tried to argue that it does indeed make some kind of sense to speak of animals and plants - rhododendrons and frogs - as having 'natures', so why should it make sense for human beings, as sort of animals, to have a nature too?

Just let me take this thought one step further.

Today, we think of the nature of animals and plants as set by their genes.

Rhodos have a nature in this sense. They have genes, and it is their genes which set them up for a particular pattern of growth, a characteristic 'pattern of life'. So do frogs. We could say that today we think of an animal's nature as the information carried by the genes.

Mustn't we say then that human beings have a nature in exactly the same way?

If so, I'm sorry to have to say that it isn't quite like nature posited by Aristotle. We can raise the question: maybe by manipulating the genes we can improve human nature.

But if 'good' consists in acting in accordance with your nature, the question of whether you might improve on nature can't be raised.

A test case for our contemporary belief about whether things have natures is what we think about genetic manipulation - where you create a new animal say, by putting genes from different animals together (not so far from the Frankenstein project).

Suppose such a manipulation were proposed. And suppose you concluded that it wouldn't cause any suffering: would you approve it?

PROMPT

Would you disapprove of the creation of a cross between a pig and a cat on the grounds that you would be interfering with the nature of these two animals, or creating an animal with a new 'nature'.

The discussion site would like to hear your arguments

I have suggested that Aristotle proposes the central importance of the idea of human nature, and holds that the good life lies in fulfilling one's nature as a human being.

Yesterday we talked about virtues. You kindly collaborated in drawing up a list of what we would identify as virtues today. The list is an interesting one.

Could we take this just a stage further? I wonder if you would, each of you, just choose a shortlist of what you judge to be the most important virtues - the things most important to you judging what virtues a person has. Ring just five from the list as I have circulated it. Let me have the sheets at the end and I will let you know what they seem to be saying.

While you are doing that with the left half of your brain, let me put to you a further nugget from Aristotle on this business of virtues.

He seems to have thought that every virtue was a sort of mid-way point between two extremes - his 'doctrine of the mean'.

Think of a person being confronted with danger. He or she might run away. Or they might react over-aggressively, perhaps throwing their lives away when such a thing was disproportionate to the situation. That is, a person might react in a cowardly way, or in a rash way. But as Tony Blair might agree, there is a third way: a middle way between these two extremes. It is the way of courage.

I give two other examples:

|

too little

|

the mean |

too much

|

|

| impulse when danger threatens |

Cowardice

|

Courage

|

Rashness

|

| attitude towards the undeserved good fortune of others |

Malice

|

Righteous indignation

|

Jealousy

|

| attitude to giving and getting |

Meanness

|

Liberality

|

Prodigality

|

|

|

|

|

The trouble is, it's difficult to see how this works with other examples of virtues. We can perhaps see it sort of works with these, but if you try it with others you might find it unconvincing.

And you may not like this idea that the middle way is the right way at all!

You may agree with Thomas Carew, writing in 1640, about mediocrity in love, and saying he for one wants the extremes - passionate love, or if not passionate love than passionate hate:

Give me more love, or more disdaine;

The Torrid, or the frozen Zone,

Bring equall ease unto my paine;

The temperate affords me none:

Either extreame, of love, or hate,

Is sweeter than a calme estate.

Give me a storme; if it be love,

Like Danae in that golden showre

I swimme in pleasure; if it prove

Disdaine, that torrent will devoure

My Vulture-hopes; and he's possest

Of Heaven, that's but from Hell releast:

Then crowne my joyes, or cure my paine;

Give me more love, or more disdaine.

Thomas Carew :Song: Mediocritie In Love Rejected

.

We have Aristotle's answer to the question of what happiness consists in. It consists in 'activity of soul in accordance with virtue'. It is living according to the pattern of life which is characteristic of the human species, performing well those activities which make that pattern up.

Happiness then is not a state of mind - it is not pleasure, for example.

Nor is it having great wealth.

Nor is it having great power.

It is engaging well in those activities which are characteristic of the species.

I say that happiness is not pleasure. But according to Aristotle it does yield pleasure. Acting according to the pattern that is characteristic of the human species, for a human being, is pleasurable.

Virtuous acts are pleasant to the lover of virtue (Nichomachean Ethics, Bk I, $8.) The life of a virtuous person 'has no need of pleasure as a sort of adventitious charm, but has its pleasure in itself.' (Nichomachean Ethics, Bk I, $8.)

Happiness does not reside in one action or another. It resides in following the rounded pattern of activities which are characteristic of the human species. Aristotle says: "For one swallow does not make a summer, nor does one day; and so too one day, or a short time, does not make a man blessed and happy." (Nichomachean Ethics, Bk I, $7)

Can we all be happy? Or are some people born with the ability to live well and others not? Aristotle thinks that some people may be born damaged in this respect - maimed. But most are born able to develop the virtuous life, which comes to them through study and practice.

"All who are not maimed as regards their potentiality for virtue my win it by a certain kind of study and care. (Nichomachean Ethics, Bk I, $9.)

There is a an approach in contemporary philosophical thought about ethics which tries to answer the central questions that arise in terms of 'virtues'. It is called 'virtue ethics'.

What is it that makes an action good or right?

You know what utilitarianism says: its consequences.

You know what the Kantian says: the fact that it is dictated by reason.

The Virtue theorist says: an action is good when it is the exercise of a virtue.

These three things may not always give different answers to the question of whether a particular action is right.

When Thomas More refuses to take the oath of allegiance to the crown and so brings on his own death, there will be different accounts of why what he does is "right".

The utilitarian will have to say: his telling the truth has the best consequences of the alternative options. .

The Kantian will say: it was right because telling a lie is irrational.

The virtue theorist will say: it was right because truth-telling is a virtue.

Let us think for a moment about what a virtue is exactly.

In thinking about ethics Aristotle certainly did place the virtues in centre stage. But his perspective on the human being as an animal possessing a distinctive pattern of life just as other animals have their own pattern of life is often ignored in contemporary reworkings of the 'virtue ethics'.

Let me therefore reprise what a virtue is for Aristotle, and how that conception fits in with his biological perspective.It is for Aristotle a disposition to behave in a certain way.

If I have the virtue of courage, I have a disposition to behave in a certain way when confronted with danger.

Similarly with liberality. If I have the virtue of liberality I have the disposition to act in a certain way when circumstances present me with the need or opportunity to give, or to receive.

Your dispositions to behave make up a large part of your life. They link situations with responses. If I am brave, I respond to moderate danger by facing up to it. If I am mean. I respond to requests for help by refusing.

So to say that the human being has a characteristic pattern of life is to say that a person who followed that pattern of life would have a set of dispositions which produced it.

The virtues are those dispositions that produce the pattern of life that is characteristic of the human being. Pursuing the pattern of life that is characteristic of the human being will amount therefore to practising the virtues. If you behave virtuously all the time, you will be living the life that is characteristic of the species. You will be living life as it ought to be.

PROMPT

If you think honesty is a virtue, what kind of argument would it be that would stand a chance of changing your mind?

I show you this, as I show you most clips, without thinking of it as 'making a point'. To a discussion of virtue and the good it is clearly relevant in a general way.

Eastwood presents what the video blurb describes as "an entirely new kind of Western hero - one who shoots first, has no ideals and is only out for what he can get. What good he does is almost inadvertent."

'Hero'?

Can such a character be someone to admire?

But I think we do admire him. What for?

Maybe it's his courage?

But if he went out there in the noonday sun and got shot to pieces it wouldn't be the same (and a short film). He has to win, or at least do well.

Or do we admire him for the good he does? I suggest that the appeal of the man with no name is not the appeal of a Mother Theresa.

I'm just showing one of the very early scenes, when Clint arrives in town, and repays those who try and run him out of it, signalling en route , significantly surely, that he is a man concerned to pay his bills.

END

Russell pic courtesy the Russell Archives

Pic credit mine except where otherwise stated.

Copyright: As far as my stuff here is concerned, anybody is welcome to use anything

VP