|

|

Introduction to Philosophy |

In the first presentation, I argued that in general terms the scientific perspective, which looks to causes, created difficulties for our belief in human freedom.

In this one I want us to look at some particular examples of sciences, or self-styled sciences, which have set out to study human beings.

Our question again will be: what are their implications for our belief in human autonomy?

The first example I want us to think about is cognitive psychology.

Cognitive science is the strongest of these. It has really replaced behaviourism as the form taken by scientific psychology.

| Mandelbrot music (sorry, this has gone somewhere. Am looking for it.) |

It is the approach which, broadly, takes the brain to be an information-processing device - a computer if you like.

It is the embodiment in serious science of the picture of the human being that has hung over our culture for some time now.

[OH The human being]

It is the picture of the human being as essentially a robot - the flesh-and-blood body - controlled by a computer, the brain.

Perhaps this picture is especially plausible against the background of what we think of the human being's place in nature.

If we think of ourselves as a product of evolution,

if we think that we have got the way we are through the workings of evolution, it is plausible to think of that survival value has attached to good information-handling, and that this is essentially what the brain is about.

It is our device for gathering information about the environment and processing it, so that we make sensible decisions - biologically sensible decisions.

It is plausible to think that this is why the human animal has been so successful. We have got better and better at information processing.

The better and deeper our 'data', the quicker and more sophisticated our ways of analysing it - the better our decision-making would have been and the keener the competitive edge.

I'm just sketching a modern picture of the human being and how we might have arisen.

|

| Courtesy Life Science Resources |

A modern picture, I mean, which many of us will share in broad outline, of the relation between ourselves and the rest of nature.

It is the picture that shows the human being as very much part of nature, a species among other species - more successful than many others, but a biological species nonetheless.

This is the picture that Darwin gave us in the 19th Century, exciting many of his contemporaries, outraging the rest.

It is not the only picture, but it is very much the one we have now.

It is sometimes hung, this picture, in a religious setting, with which I guess it is compatible. We may be the product of evolution, it may be said, - we may be a species among other species, but there is, behind evolution - behind the physical universe and its laws - a Being, a Being who made it all, perhaps sustains it all, perhaps cares for it all.

Either way, with God in the background or not, this Darwinian picture of the human being as the immediate product of natural evolutionary processes has a place for the brain.

It supports the idea that the brain has evolved as an information processor to bring ever more intelligent control over the body.

But you can see I think how this conception of the brain carries with it the threat of determinism for human beings.

What room is there in an information-processing device for autonomy or freewill?

We will be coming at the computer-driven robot conception of the human being from more than one angle in this course.

One problem that has continued to exercise philosophers throughout the Modern period - I mean since the 17th Century - is the nature of the mind.

If we are robots, even computer-driven ones, could we have minds? Could we be conscious?

This is a question that you will come back to in due course. The question now, in the context of determinism and free-will, is whether a computer could have free-will.

[OH What characters in]

Like the question of time-travel, the question of robots thinking for themselves appeals to the public imagination too. Though this is nothing terribly new.

Can you think of some characters in fiction or film that are presented as examples of a machine becoming autonomous?

There are interrelated issues, with films differing on their focus.

|

| Dr Frankenstein in his laboratory, still from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Director of Photography Roger Pratt. Courtesy Resources for the study of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein by Martin Irvine |

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein for example focuses on the hubris of science in daring to emulate God. There is the question of whether robots could be got to feel - we think of Arnie in Terminator 2, coming to an understanding of sorrow, but knowing that he himself could never weep.

· Star Trek is concerned with the emotionality of human beings, the Vulcan representing rationality which begins cold but acquires an emotional underpinning which is more and more apparent, and more and more impregnable as the stories develop.

· There is the capacity to learn, emphasized by War Games, where the computer has to learn in order to give up his deadly game of Nuclear War.

· And then there is autonomy itself. HAL in 2001 was thought by the astronauts to have developed a will of its own - though they were I think, according to the plot, mistaken about this. There is the intelligent nuclear bomb in Dark Star, which is led to see the force of the Cartesian argument I think therefore I am and is persuaded to stop the countdown which would annihilate it (and its astronaut companions) by the thought that its input may be false.

[OH Feeling]

Summary: MIGHT MECHANISMS BEGIN TO DISPLAY AUTONOMY? TWO POSSIBILITIES PERHAPS

What you have in the imagination of a whole host of science fiction writers is the prospect of artificial, human-made, devices getting out of control.

Not in the way a lorry's brakes fail with it careering blindly down the hill but somehow escaping their programming, becoming independent, acquiring ideas of their own, acquiring autonomy and exercising it to pursue those ideas, perhaps at the expense of those who manufactured them.

How are we to think of this possibility - the possibility of mechanisms becoming autonomous?

The issues here are presumably the same as those involved in asking whether we ourselves might be mechanisms but at the same time autonomous.

Here is one line of thought.

As you program your robot in ever more sophisticated ways, programming it not just with oodles of information but with the capacity to learn, to acquire and systematize new information as it goes along, as the program gets bigger and bigger, more and more complex, what you will get is a robot which is gets more and more like human beings.

And there will come a point, some people predict, don't they, when you won't be able to tell the difference.

|

|

Alan Turing, courtesy Alan Turing.net, an excellent site on Turing, thanks to Jack Copeland and Gordon Aston Great resource on the Turing

test, thanks to Ayse Pinar Saygin Here is Turing's 1950's paper "Computing Machinery and Intelligence." You can talk to Eliza here and to Brian here (Can't get anything out of Brian at the mo, sorry. And Eliza does seem very sad.) |

Alan Turing, a major 20th Century figure, rather neglected, who worked just down the road at Manchester, set this out as a formal test. Not for autonomy exactly, but for 'thinking'.

He said the moment you can't tell the difference between a machine and a human being you will have to say the same things about both.

If one is autonomous, you will have to grant the other must be.

If you say one is capable of thought, you will have to conceded the other is capable of thought as well.

Imagine you have a machine for which thought is claimed. Put it up against a human being and see if you can tell the difference. This was his proposal.

His idea was just to eliminate the distraction of the physical appearance and mode of communication of an artificial thinker.

[OH Alan Turing]

Put him or her or it in a private room, he said, and let all communications between him/her/it and the examiners, who sit in a room by themselves, be done through a keyboard.

In another private room put a human being, also communicating via a keyboard.

Get the examiners to ask what questions they like through their keyboard. The responses of the human being and the computer come up on different screens.

If after the 'conversations' have gone on for some time the examiners can't tell which are the responses of the human being and which the computer, the computer is deemed to have passed the test.

| Questioner: Aims to discover if A or B is the Computer |

Questions |

|

(Thanks to Larry Hauser)

What would be a reasonable period for this test, do you think?

(A) TRUE AUTONOMY TURNS OUT TO BE A MYTH AS HIGHLY COMPLEX MECHANISMS MIMIC IT SUCCESSFULLY.

(B) TRUE AUTONOMY 'EMERGES' FROM HIGH FULLY DETERMINED COMPLEXITY.

Once you have got a machine that passes the Turing Test, what moral will be there for autonomy?

[OH Two possibilities]

Here is a mechanism, you may say, which is behaving exactly like a human being.

But we made it! We know it is a mechanism. We programmed it to work in a certain way. Because we can get a machine to copy human behaviour in this way, human freedom is a myth.

There is though another way you could point the gun - often in philosophy an argument can be pointed in more than one direction.

B. TRUE AUTONOMY 'EMERGES' FROM HIGH FULLY DETERMINED COMPLEXITY

You could say: here is what we thought was a mechanism - an elaborately programmed computer - but what we discover is that it can be got to mimic human behaviour. We know that human beings are autonomous. These things that we have made and have thought of as mechanisms are evidencing freewill. Therefore they cannot really be mechanisms at all. They may have begun as mechanisms, but somehow they must have 'taken off', as it were - turned into something of a different order - turned into system capable of free choice.

A term that is sometimes used in this connection is 'emergence'.

Something utterly new it is said 'emerges' from what began as mechanism.

There are precedents for this kind of thing, it is argued. At one time, so it is believed, there was nothing but gas. Different elements, but all in the gaseous state. At a certain temperature, and as conditions modified, some of the gases combined. Oxygen and hydrogen combined and produced something with a property that had not occurred before. What they produced was water and the innovative property was wetness.

Might not freedom be like that - something utterly new that emerges when mechanical contraptions get above a certain level of complexity?

Can you think of other examples of 'emergents' - really new things or really new properties that emerge from what went before.

Summary of Determinism 2 to this point

Application of the scientific perspective to the human being

Cognitive Science - the brain as an information-processing device

A test for machines: the Turing test

Could autonomy emerge? - could what starts as a mechanism turn into something with autonomy?

|

"The fundamental problem ... of the social science, is to find the laws according to which any state of society produces the state which succeeds it and takes its place." |

| J.S.Mill |

The theory of evolution by natural selection was put forward by Darwin (and Wallace!) in the mid-nineteenth century - and it concerned the development through time of types of animals and plants. In the same period - before and after Darwin - there were suggestions that we should think of a process of 'evolution' occurring amongst societies.

The nineteenth century polymath Herbert Spencer was responsible for proposing perhaps the closest parallel between organic and social evolution. Social evolution, which begins, he proposed, with a number of elementarily simple forms of society, from which arise a wider and ever-widening diversity of forms of ever-ascending orders of complexity.

[OH Spencer]

In other words, just as the diversity and complexity of modern animals and plants are supposed to have evolved from one or a few simple primeval organisms, so Spencer supposed that the varied and sophisticated societies of his day could trace their ancestry back to one or two ancient social systems of simple organization.

That's Spencer.

A different 'evolutionary' thesis leaves out all talk of a common root for modern societies and insists more simply that all societies pass through one and the same developmental path.

The view of Auguste Compte, one of the spirits behind modern sociology, writing before Darwin, was of this kind.

According to Compte, any society had to pass through three stages.

[OH Compte]

What binds a society together? asks Compte. In the beginning, force and fear of force. You have, he says, a first stage of militarism.

In the next stage - the 'legal' - these factors are replaced by respect for the law and constitution.

Finally the ultimate stage of industrial organization is attained. The binding power now becomes - science.

(In fact Compte thought of science as the basis for a kind of religion, a religion which was to have, as he planned it, priests and liturgy, catechism and calendar. a religion to counter the social fragmentation and relieve the uncertainties which he thought were driving Europe into a desperate state in the midst of the upheavals of the early 19th Century.)

| A more recent highly influential theory, by W.W.Rostow |

The view that social change within a particular society follows a fixed pattern has attracted the attention - beginning in the second world war and persisting since - of a singular critic: Karl Popper.

Popper begins by stressing what he sees as the fundamental doctrine of what we are calling evolutionism, the doctrine that, because social change within a society follows a fixed pattern, it is capable of being predicted.

The evolutionist position thus implies that a society's history could be written in advance.

Approaches to society that concentrate on these predictive possibilities - and Popper thinks that this is generally true of what we are calling 'evolutionism' - Popper labels 'historicist':

Popper has what he thinks is a decisive objection to evolutionism, or 'historicism', as he calls it.

It is based, he declares, on a simple demonstrable mistake.

We must agree, he argues, that change in a society is often influenced by its members' acquisition of new knowledge.

The course of our own society, for example, has surely been influenced by the invention of the steam engine, and by the 'discovery' of North America, and by our determination of the structure of the carbon atom.

But if there is one thing we cannot know now, it is what we shall only come to know in the future.

To anticipate an invention is to make it.

It follows, Popper concludes, that predicting the course of social change in the future is impossible, and 'historicism' stands refuted.

[OH Popper's criticism of 'historicism']

Popper is passionate in his denunciation of historicism (evolutionism) because of the practical dimension of the issue of determinism that I pointed out last week.

Popper took this very seriously.

If the historicist (evolutionist) is right - if social change occurs in conformity with some fixed pattern - it would seem to follow that the future of any society is as fixed as its past.

Human responsibility is thus denied: whatever change a society undergoes must be seen as the product of a determinate historical process, in which the individual is powerless to intervene.

Popper at any rate thinks we are thus confronted with an idea that affects human responsibilities in the deepest possible way.

Accept historicism and we one must also accept that attempts to influence the course of events, to oppose unwelcome change, to bring in reforms or, even more, to inspire revolutions are entirely pointless.

According to this view, 'politics are impotent', as Popper puts it.

Do you think societies evolve according to a fixed pattern?

If so, what will happen next?

Popper thought Marxism came under the historicist category, and Marxism was indeed his chief intended target.

It seems strange to accuse Marxism of political resignation - of political quietism - - of robbing would-be revolutionaries of all hope of influencing events.

But Popper is not alone in thinking of Marxism as maintaining that the human race has pursued and will inevitably pursue a fixed pattern of development.

Insofar as this account of it is correct, Marxism becomes one of the most important evolutionary theories of society ever put forward.

Let us just sketch it then.

He first identifies a tribal condition, in which the structure is little more than an extension of that of the family and the necessities of life are met by hunting and fishing, by cattle breeding or by agriculture.

When several tribal units unite to form a city, a second stage is reached, in which the necessary productive labour is performed by slaves.

The third stage is represented by Feudalism: slaves are replaced in the country by an enserfed small peasantry and in the towns by journeymen; their productive activity is limited to small-scale and unsophisticated cultivation of land, and handicraft industry.

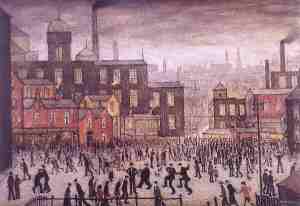

|

| 'Our Town' by LS Lowry |

Out of feudalism comes capitalism, with production being performed largely with the use of machines and society divided into those who own the machines and those who operate them: the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

Marx goes beyond identifying and describing the main stages of Western European development as he sees it: he describes the mechanism by which he thinks social change occurs.

Marx thinks that the important thing about a society is its way of producing life's necessities - how it organises the production of food, shelter, warmth and so on. It is, thinks Marx, the way a society organises itself to produce these things which determines its other, less basic characteristics.

Consequently, he thinks it is change in this aspect of its life that leads to change in the society as a whole and thus determines its historical course.

| More detail on Marx's theory of how change comes about |

It is the struggle to make life more and more comfortable that drives the development of society forward. The way we organise ourselves in order to produce life's necessities changes as new and more efficient ways of producing things are devised - until we end up with the modern Western society (19th century Western society for Marx) where human beings are organised so as to work large-scale industrial plant and machinery.

So there is a final, still contemporary, example of science, the scientific approach, applied to society or social change.

We are not talking atoms and nuclear forces here - we are talking about social structures and social forces. But the causal analysis is there. The attempt is to explain the causes of social change.

Summary of second half of Determinism 2

The application of the scientific perspective to the study of human groups

Social evolutionism -eg Spencer, Compte

Popper's argument against determinism in human history

Another example: Marxism

I want to turn away from social evolutionism now.

I want to turn back to the individual.

I was asking about whether human beings could be seen as machines.

A lot of people used to say the great thing about human beings is that they can learn. With machines you have to programme everything into them - give them all the data, and give them a programme which tells them exactly what manipulations they are to apply to it. Whereas human beings are not pre-programmed like that. We learn. We acquire not only new knowledge but new things to do with it. Programs are just lists of definite instructions. You can't program a machine to learn to do new things.

The clip I have now doesn't prove that is wrong of course. It is a work of fiction. But it gives us a concrete example to think about. It invites us to think about a machine that is able to learn, and it's this capacity which saves the world.

It's a Cold War movie. Joshua is a programme running in a machine called WOPR. The program thinks it is playing a game called Global Thermonuclear War, when in fact it is controlling the United States nuclear arsenal for real.

When the human beings attempt to stop it, it locks them out and carries on playing, searching for the codes which will enable it to launch the missiles.

The strategy, conceived by our brilliant hero, is to use its capacity to learn to reach the conclusion that some games cannot be won, and that Global Thermonuclear War is one of them.

He gets it to realize this by getting it to play noughts and crosses against itself. This is a game you can't win against an expert opponent. The machine learns this, then checks to see if it applies to the game it is currently playing, Global Thermonuclear War, sees that it does, gives up that game in favour of something it can win, Chess.

We join when the people in the war room are just about to realize that the machine has locked them out...

END

Menu of VP's 100/200 presentations

Last revised 10:10:03