Record low unemployment gives no cause for celebration amidst alarming rise in inactivity

Posted on

This month’s labour market statistics present a complicated picture that hints at a difficult winter ahead.

Despite unemployment falling to lows not seen in nearly half a century, this quarter saw an alarming increase in the number of people who are out of work and not looking for a job due to long-term illness. Although the private sector has seen strong pay growth, the public sector is lagging and inflation in the double digits is erasing gains. Alongside the Government’s support for energy bills announced last week, Ministers must develop a Plan for Participation for the labour market, which should include supporting those who want to get into work and driving up good work.

Interpreting unemployment figures in the context of other statistics

The unemployment rate in May-July 2022 fell to the lowest it has been since 1974, at 3.6%. Although unemployment figures are often used as a benchmark for the health of the labour market, the decrease in employment levels and rise in inactivity give reason to believe these new figures are no cause for celebration.

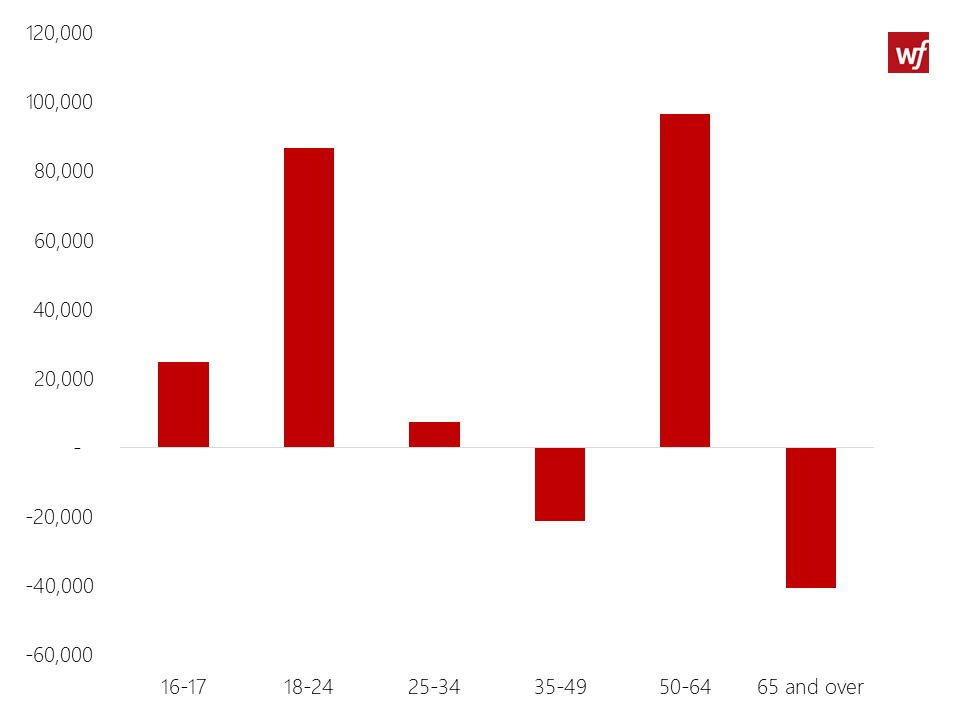

Despite the drop in unemployment, this quarter saw a decrease of about 25,000 in overall levels of employment among those aged 16-64 years old. This suggests that although some unemployed workers may be moving into employment, overall there is a net flow from employment and unemployment into economic inactivity, which means being out of work and not looking for work.

This quarter saw a concerning rise in inactivity

Inactivity levels have increased by 194,000, up to 21.7%. Most concerning is the growth in people who say they are not looking for work due to long-term sickness, which was up by 130,000 over the past quarter.

For young workers aged 18-24, a reduction in short-term unemployment and increased economic inactivity due to full-time education suggests that young workers who were out of work have opted to continue, or return to, education.

Among those aged 50 and over, a decline in long-term unemployment suggests that despite consistently high vacancy levels, some older workers are struggling to find work and may opt to leave the labour market, as evidenced by the strong increase in inactivity levels among this age group.

Figure 1: Quarterly change in inactivity levels, by age group

Source: Work Foundation calculations based on ONS (13 September 2022) Dataset A01 September – Labour market activity by age group (seasonally adjusted). This figure represents changes in the levels of economic inactivity between February-April and May-July 2022.

Older workers aged 65 and over continue to join the labour market

Employment levels among those 65 and over has continued to grow this quarter, increasing by 60,000. This suggests that older workers, in a continuation of last quarter’s trend, are continuing to join the labour market, likely due to cost of living pressures. This increase, however, is lower than we saw earlier this year, when this number increased by a record 173,000, driven by part-time work in industries such as hospitality, arts and entertainment and recreation.

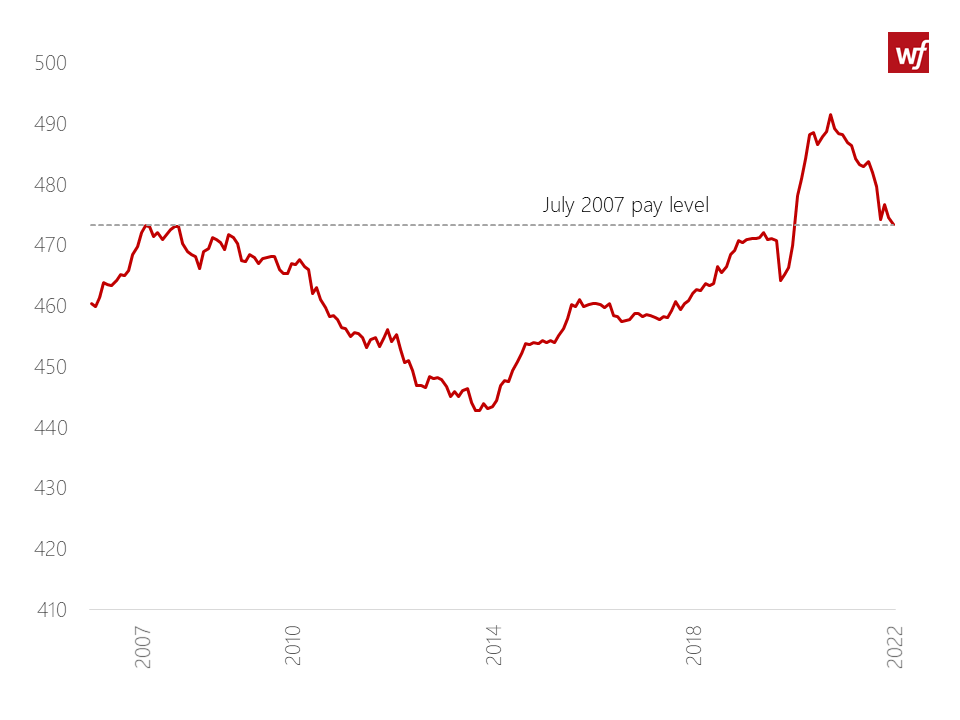

The UK’s fall in real pay compares unfavourably to other countries

With inflation at 10.1%, the real value of wages continues to fall. Although the private sector has experienced relatively strong pay growth of 6.0%, these gains are outpaced by inflation. The real terms pay cut is felt even more harshly in the public sector, where pay has grown by just 2.0% on the year. The real value of average wages is now similar to what they were in the summer of 2007. This follows more than a decade of wage stagnation that only recently started to recover, and has now again been wiped out.

Across the economy, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates that real average pay fell by 2.8% between 2021 and 2022. The UK’s fall in wages is reportedly one of the largest among countries that belong to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation), which fell on average 2.3% on the year.

Figure 2: Change in real average pay between July 2006 to July 2022, at constant 2015 prices

Source: Work Foundation calculations based on ONS (13 September 2022) Dataset A01 Average Weekly Earnings at Constant 2015 Prices (Great Britain, seasonally adjusted).

Driving up job standards

This quarter, we would have expected to see the cost of living crisis push people back from inactivity into the labour market, and although that is visible particularly among older workers aged 65 and over, we are also witnessing some workers leaving the labour market, such as workers aged 50 to 64 years old. It is important that we come to grips with why this is happening. While the ONS increasingly deliver responsive analyses on developments in the labour market, more work could be done to understand what is driving the increase in long-term sickness and how people balance considerations between rising financial pressures and the realities of work.

Government should prioritise a new Plan for Participation, as we have emphasised previously. This should focus on an offer of personalised support for those who are out of work and want to work. This support is essential for workers who experience barriers to accessing work and remaining in work, such as workers with disabilities and health conditions and older workers.

And to ensure that workers who might return to the labour market are incentivised to do so, Government should work with employers to improve job design, to provide the kinds of flexibility that is so essential to so many to enter or remain in work.

Related Blogs

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing