What are the implications of the new immigration system for UK labour supply?

Posted on

© Photo by Kev Seto on Unsplash

© Photo by Kev Seto on Unsplash

The UK’s new points-based immigration system came into force last week, bringing 47 years of freedom of movement with the EU to an end. The new measures mean rules and thresholds will now determine whether EU nationals can live and work in the UK, putting many in direct competition with workers from the rest of the world.

Our new analysis finds that up to 160,000 EU workers who arrived in the UK over the last three years would not have been eligible to live and work here had the new immigration rules been in place.

Over time, this could fundamentally change the profile of the EU workers participating in the UK labour market, arguably concentrating competition for jobs in higher skilled roles, and leaving labour shortages in sectors that have tended to rely on EU workers most.

Under the new system, most EU workers entering the UK must hold a job offer from an employer willing to sponsor them before they can apply for a visa. To be eligible for a visa, these jobs must pay at least £25,600 and require skills at A-level or equivalent.

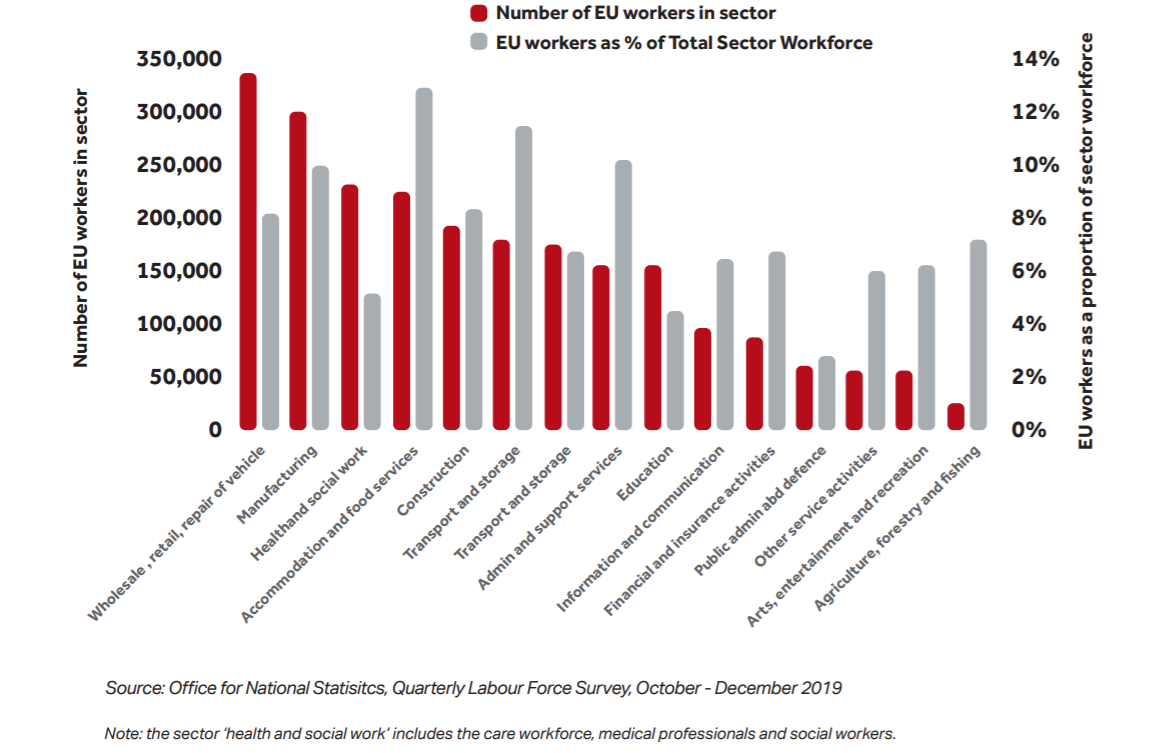

While all sectors will be affected by the ending of free movement, some will face more acute challenges than others. Hospitality businesses employ the highest proportion of EU workers (13%), followed by transport and storage (12%) and administration and support services (10%). In other sectors, the number of EU workers is particularly high, for example wholesale and retail (344,374) and health and social work (235,227), reflecting the scale of the workforce.

Figure 1: EU Nationals Working in the UK by Sector, 2019

While there will be a Health and Care Worker visa, allowing nurses, doctors, social workers and some other health professionals with a confirmed job offer to come to the UK, many care workers will not qualify for this visa. Our analysis has found that had the new rules been in place over the last three years, up to 11,000 EU workers who have arrived and worked in the NHS, social services and social care would also have been unlikely to pass the new immigration criteria.

Social care is a sector under immense pressure, and with demand set to grow exponentially coupled with the longstanding challenges in attraction, recruitment and retention of workers, the end of freedom of movement marks a significant risk for the sector. Early monitoring and engagement with the social care sector should be prioritised as the new system is implemented. Going forward, there is the need for a strategic approach to workforce planning in social care. Government should focus on improving working conditions for existing and future workers to enable the Social Care to grow sustainably in line with demand.

Similarly, had the new rules been in place over the last three years, we estimate that up to 40,000 EU workers who have arrived and worked in hospitality would also have been unlikely to pass the new immigration criteria.

The hospitality sector is the largest proportionate employer of EU workers. However, the end of freedom of movement will mark a significant turning point for the sector, and employers in the sector won’t be able to draw on European workers as they have done in the past. While the current economic circumstances mean that Brexit likely won’t cause a sudden labour supply crisis in the sector over the shorter term, in the longer term hospitality will recover and could experience difficulties unless remedial actions are taken.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing