196 THE STONES OF VENICE CONSTRUCTION

which1 I have already spoken as, I suppose, the most perfect architecture in the world.

§ 11. In less important positions and on smaller edifices, this cornice diminishes in size, while it retains its arrangement, and at last we find nothing but the spirit and form of it left; the real practical purpose having ceased, and arch, brackets, and all, being

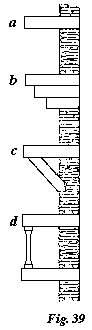

§ 12. I wish, however, at present to fix the reader’s attention on the form of the bracket itself; a most important feature in modern as well as ancient architecture. The first idea of a bracket is that of a long stone or piece of timber projecting from the wall, as a, Fig. 39, of which the strength depends on the toughness of the stone or wood, and the stability on the weight of wall above it (unless it be the end of a main beam). But let it be supposed that the structure at a, being of the required projection, is found too weak: then we may strengthen it in one of three ways; (1) by putting a second or third stone beneath it, as at b; (2) by giving it a spur, as at c; (3) by giving it a shaft and another bracket below, d; the great use of this arrangement being that the lowermost bracket has the help of the weight of the shaft length of wall above its insertion, which is, of course, greater than the weight of the small shaft: and then the lower bracket may be farther helped by the structure at b or c.

§ 13. Of these structures, a and c are evidently adapted especially for wooden buildings; b and d for stone ones; the last, of course, susceptible of the richest decoration, and

1 [i.e., of the Campanile: see Seven Lamps, ch. iv. § 43 (Vol. VIII. p. 187).]

[Version 0.04: March 2008]