Issue 4: Hidden Voices

Of Spectacle and Grandeur: The Musical Rhetoric of Private vs. Public Ceremony in Showtime’s The Borgias

Maria A. Kingsbury and Stephen A. Kingsbury

Season One of the Showtime series The Borgias premiered on April 3, 2011. Created and written by Neil Jordan and starring Jeremy Irons, Francois Arnaud, Holliday Grainger, Joanne Whalley, Lotte Verbeek, and David Oakes, the series colourfully relates the story of the Italian dynasty of Spanish origin, which, through the ascension of Rodrigo Borgia (Irons) as Pope Alexander VI, rose to power in the late 15th century’s Catholic Church. Through means of political machinations, as well as nefarious acts of simony, bribery, adultery, incest, rape, and murder, the Borgias become one of the most influential, as well as notorious, families of the age. In the process, they amass great power, wield vast influence, and become important patrons of the arts.

A significant feature of the pilot episode of the Showtime series lies in the visual techniques differentiating ceremonial public scenes from ritual in private spaces. The dichotomy between exterior and interior, however, is complicated by the musical selections underscoring the visual narrative. Strikingly, the pilot episode of The Borgias utilizes music from two very distinct sources. The first source is original music, composed specifically for the series by Trevor Morris.1 As one might expect, Morris’ score provides the backbone for the episode’s soundtrack. However, at several key points music from other, historical, sources is employed.

In sum, four other works are used at five significant points in the narrative. These points are particularly noticeable, as the music is remarkably distinctive from that of Morris’ score. Although Morris’ music employs elements that suggest reference to the place and time in which The Borgias is set, it is distinctly contemporary in approach and affect. Conversely, the music that is drawn from other sources is distinctively historical in nature, serving to create a different and distinct rhetorical referentiality. The use of this historical music takes on specific import because the scenes in which it is used are transitional and highlight the tension between public and private space as well as public and private knowledge, and ultimately prove to be an ethos-driven appeal to the viewer’s interpretation of the narrative.

Although Morris’ score and the manner in which it is used in the pilot is a subject that is worthy of study, this paper will focus instead on the historical music, particularly as it relates to the dichotomy between public and private ceremony. While both public and private spaces are utilized for ritual-spectacle, the difference in the music that is employed delineates the nature of each space. This paper examines the dialectic created by these differences, particularly through the use of irony and anachronism, in order to determine the rhetorical message presented by the series’ writers and producers regarding the nature of private ceremony and public spectacle. Further, the implications of this rhetorical message are examined as it pertains to the emergence of new media forms within contemporary popular culture.

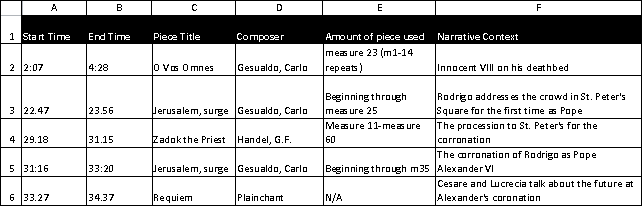

As mentioned, the pilot episode of The Borgias employs four pieces that were not composed by Morris, used over the course of five distinct scenes (Figure 1). Of these, the use of Handel’s Zadok the Priest is particularly striking. This piece is used quite prominently and is extremely easy to identify. The other historical works, at least upon first viewing, seemed of a period with the setting of the show, whereas the Handel, distinctively Baroque in style, even to a non-expert in music history, clearly did not. While television audiences regularly accept anachronistic modern scores in historical dramas, the use of the Handel score, with its use of orchestral strings, strident brass fanfare figures and choral parts presented in clearly enunciated English, suggests that the television show’s producers have a more nuanced intention than simply including mood music; the Handel piece is greatly out of context—but only to an astute viewer. Such a realization calls into question the nature of the other works that are employed. A close reading of the episode yields that none of the music employed is from the same time period as the setting of the narrative. In addition to the Handel, the producers chose to employ two works by Carlo Gesualdo, and one example of plainchant. Why are these pieces, which may sound to casual viewers in keeping with the 15th century Italian setting, employed as opposed to Trevor Morris’s original score? Or, if the creators’ intent is to startle the viewer into allowing the music to become a greater dramatic presence, why select pieces that are relatively obscure?

Figure 1- ‘Historical’ Music Employed in Episode 1

In order to answer these questions, and to offer potential insights into the incorporation of anachronistic music into the broader array of period television shows that are presently proliferating on network and cable, we undertake an investigation of the ‘historical’ musical works incorporated into the first episode of The Borgias. Combining an historical musical analysis with rhetorical analysis of the placement of those pieces within the narrative structure indicates that viewers may be afforded valuable thematic and dramatic insights into the melodramatic spectacle of the Borgia dynasty.

These four pieces, with their rich and storied history and contexts outside the realm of The Borgias, simultaneously indicate the dramatic importance of the scenes and suggest complicated historical and dramatic truths concealed beneath the surface appearance of the characters and events. It is only when viewers employ their own knowledge of the musical context, moving beyond unstudied consumption of seemingly authentic musical selections, can the episode’s (and, arguably, the series’) themes be thoroughly explored. Strangely, then, but in keeping with the series’ ongoing subtext of subterfuge and concealment, the musical anachronisms provide timely and relevant insights into The Borgias’ narrative.

The Historical Music

Carlo Gesualdo (1566-1613) was a prince of the Italian city of Venosa; he was extremely wealthy and very well connected with both the church and the aristocracy. As a composer, Gesualdo is best known for his madrigals, but even his fame stemming from these stunning works pales in comparison to the infamy created by his life story, a decline which ultimately bears upon the selection of his work for this particular episode of The Borgias. He is most notorious for having brutally killed his first wife, his cousin Maria d’Avalos, and her lover, the Duke of Andria, on October 16 1590 when he found them in flagrante delicto di fragrante peccato. Because of his princely status, no legal action could be taken against him; however, Gesualdo remained the potential victim of revenge plots carried out by his victims’ families. In order to avoid such plots, Gesualdo withdrew to his estates in the town of Gesualdo, where he resided until his death in 1613. During this time, he made several trips to Ferrara, where he was greatly inspired by the famed musical establishment maintained by the D’Este family. He deepened this connection to Ferrara when he married Leonora d’Este, a niece of the Duke of Ferrara, Alfonso II, d’Este.2 Towards the end of his life, Gesualdo’s physical and mental health deteriorated drastically. He was extremely masochistic, and suffered from violent asthma. His only surviving son with Leonora died at the age of five. Additionally, he was abusive towards Leonora, who was apparently carrying on an affair with a Cardinal.

As a composer, Gesualdo’s music is ‘mannerist’ in approach, although it is unique in aesthetic. It simultaneously exhibits both conservative and avant garde traits. It is conservative in that it does not look forward to the structures and techniques of the Baroque period and avant garde in that Gesualdo often abandons the established conventions of composition in order to create music that underscores the extreme emotion within the texts being set.

Both of the works by Gesualdo heard within the pilot episode date from the period of declining health at the end of his life where this emotional drive finds its most profound and dramatic expression. Both are settings of texts from the Tenebrae Responsories for Holy Saturday that were published in 1611 in Gesualdo’s Responsoria et alia ad Officium Hebdomadae Sanctae spectantia. Tenebrae, meaning darkness or shadows, is a Christian service held during Holy Week on the evening before or in the early morning hours of Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday, respectively. In the Catholic tradition, these services take place during the canonical hours of Matins and Lauds (held at midnight and three o’clock in the morning, respectively). The service features a series of readings as well as the recitation or chanting of psalms. Additionally, over the course of the service, candles are gradually extinguished, eventually leaving the celebrants in total darkness. These services take on a particular poignancy on Holy Saturday, as this service commemorates the time between the death of Jesus on the cross on Good Friday and his resurrection on Easter Sunday.

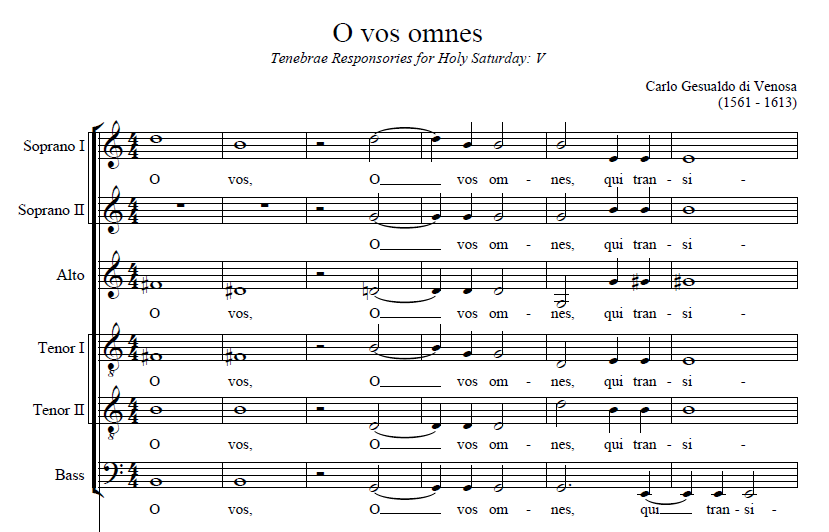

The first of Gesualdo’s works to appear in the pilot is his six-voiced motet O Vos Omnes (Figure 2). This workis Gesualdo’s second setting of that text, which is the fifth Responsory from the Holy Saturday Tenebrae Service.3 The text, which depicts the prophet Jeremias’ lament over the fall of Jerusalem and the ensuing Babylonian Captivity, is based on Lamentations of Jeremiah 1:12. It reads as follows;

O vos omnes qui transitis per viam, O all you who pass along this way,

attendite et videte: behold and see

Si est dolor similis sicut dolor meus. if there is any sorrow like my sorrow.

Attendite, universi populi, Behold, all you peoples of the world

et videte dolorem meum. and behold my sorrow.

Si est dolor similis sicut dolor meus. if there is any sorrow like my sorrow. (Jeffers 182)

Figure 2: O Vos Omnes

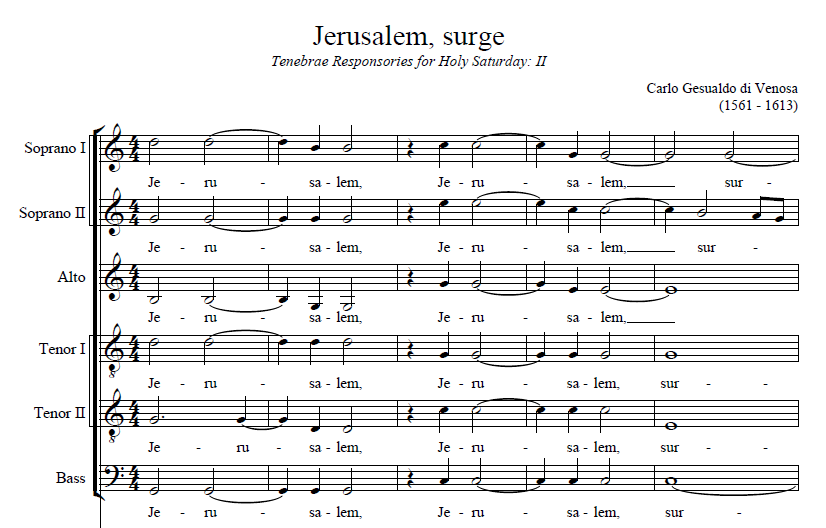

Like O Vos Omnes, Gesualdo’s Jerusalem, surge (Figure 3) was composed for six voices (SSATTB). The text of Jerusalem, surge serves as the second Responsory of the Tenebrae Responsories for Holy Saturday. Here, Jerusalem is admonished to mourn the death of Christ. The text is based on Jonah 3:6 and Lamentations of Jeremiah 2:18 and reads as follows;

Jerusalem, surge, et exue te vestibus Arise, O Jerusalem, and put off your garments of

jucunditatis; induere te cinere et cilicio: rejoicing; cover yourself with sack-cloth and ashes:

quia in te occisus est Salvator Israel. for the Saviour of Israel has been slain in your midst.

Deduc quasi torrenem lacrimas Let your tears run down like a river,

per diem et noctem, day and night,

et non taceat pupilla oculi tui. and let not the apple of your eye cease.

Figure 3: Jerusalem Surge

George Frederic Handel (1685-1759) stands as one of the most significant composers of the Baroque period. His anthem Zadok the Priest was written for the coronation of England’s King George II. King George I died on June 11, 1727. Four days later, his successor was proclaimed King George II. Preparations were immediately underway for the coronation of the new king and his consort, Queen Caroline. Under normal circumstances, the music for the ceremony would have been entrusted to the Organist and Composer of the Chapel Royal, who was at that time William Croft. However, Croft himself died soon after the King. Four days after Croft’s passing, the Bishop of Salisbury recommended Maurice Greene as Croft’s successor, but it soon became clear that Greene would not be asked to provide the music for the coronation. Instead, on personal appointment from the King, George Frederic Handel was commissioned to compose the anthems. Contemporaneously, Handel held the appointment of Composer of the Chapel Royal, having been named to the post by George I in 1723. There is some evidence to suggest some ill feelings between Handel and Greene as a result of this set of circumstances. Greene may have felt slighted by the King’s insistence on having Handel compose the music, and Handel may have coveted Greene’s position. However, tradition held him ineligible for this position, as it was reserved specifically for a native Englishman, and although Handel spent much of his career working in Britain, he was a native German by birth.

All told, Handel composed four anthems for the coronation service; Zadok the Priest, Let thy Hand be Strengthened, My Heart is Inditing, and The King Shall Rejoice. He chose his texts for each anthem from the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer, and, in the case of Zadok... and Let thy Hand..., from the texts of the 1685 coronation, which had recently been reprinted.

Despite some confusion at the coronation ceremony in regards to the logistics of their performance, the anthems became an immediate popular success.4 In each anthem, Handel’s background as an opera composer served him well. He seems to demonstrate a comprehension of the dramatic needs of the moment. His complete understanding of the nature of the human voice, as well as the immense artistry with which he constructed his melodic lines, makes for a set of works that are uniquely suited to the goal for which they were conceived. However, they are not representative of the composer at his most profound; they simply do not possess the more subtle characteristics of the operas or the oratorios. Instead, they are perfectly suited to their purpose; highly ceremonial music designed to match the grandeur of the coronation ceremony as well as the opulence of Westminster Abby, the space in which they were performed.

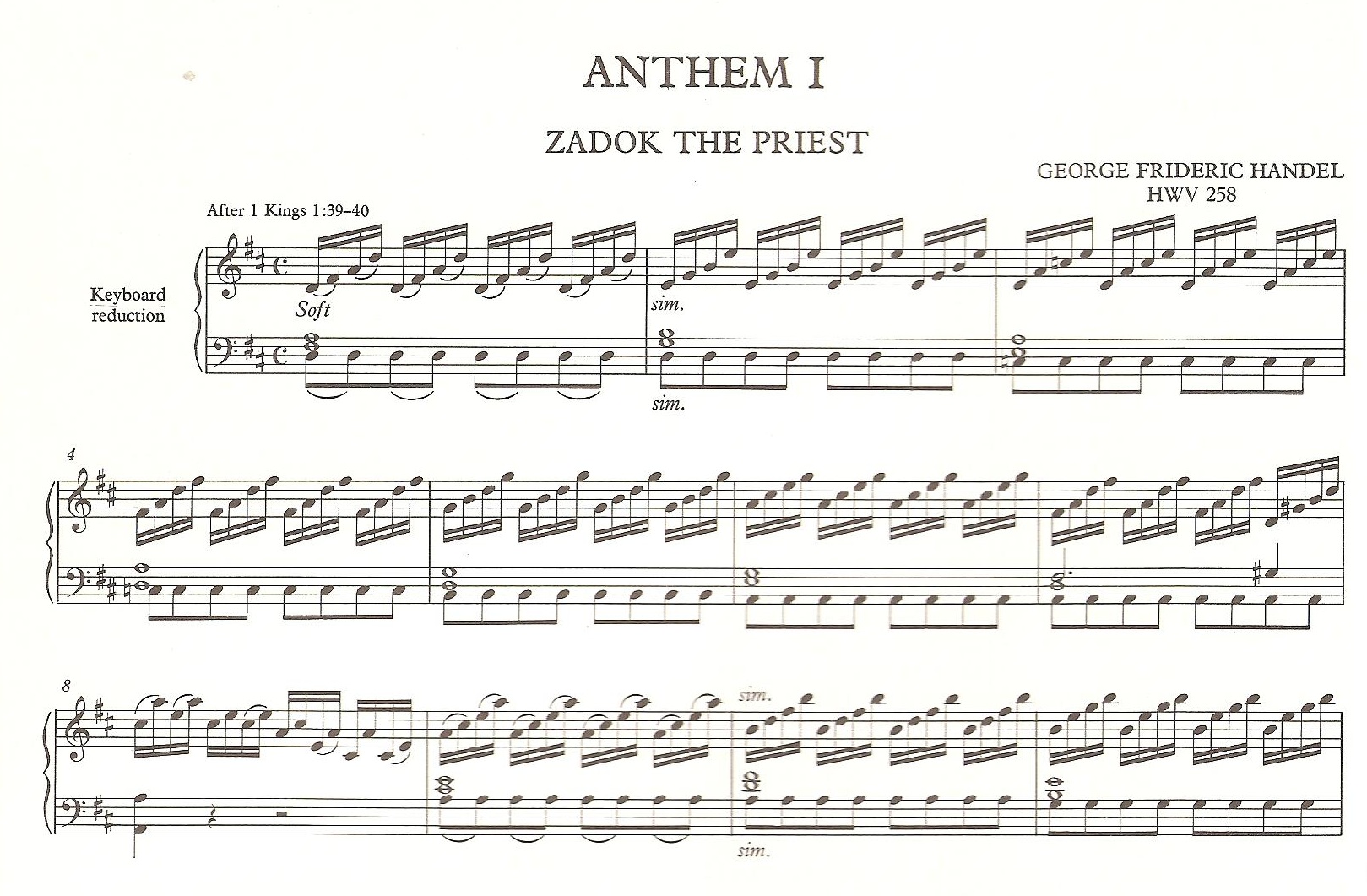

Zadok the Priest (Figure 4) is the shortest of the four anthems that Handel composed. Written for seven-part chorus and orchestra, the work is divided into three structural segments; an opening fanfare, a triple-time dance, and a joyous ‘alleluia.’ Used at the anointing portion of the ceremony, Zadok has been performed at every British coronation since it was first composed. The text is drawn from I Kings I, King James Version and depicts the anointing of King Solomon:

Zadok the priest, and Nathan the prophet anointed Solomon King.

And all the people rejoic’d and said:

God save the King! Long live the King! May the King live for ever, Allelujah, Amen. (I Kings I 39 and 40)

Figure 4: Zadok the Priest

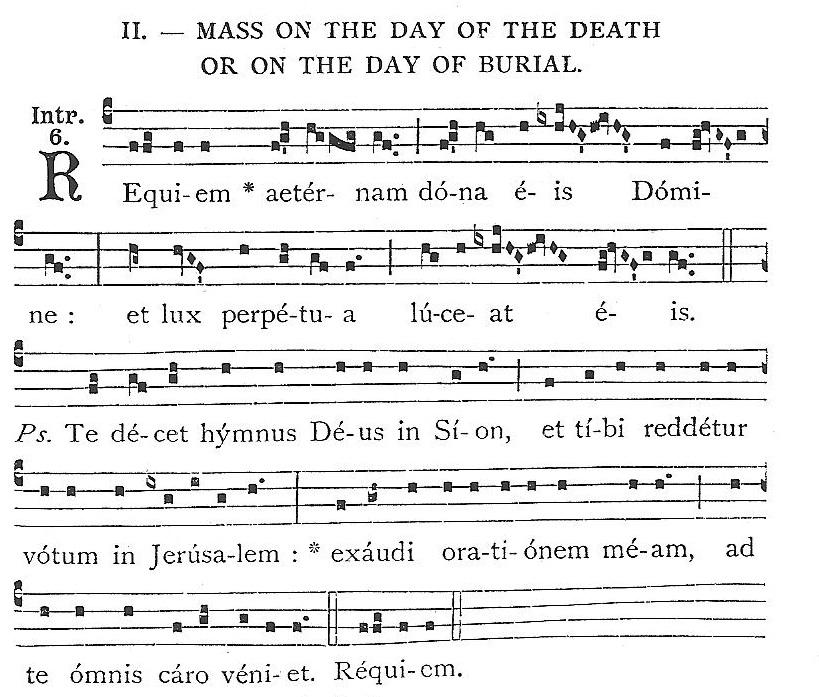

The last piece of historical music employed by the producers is the plainchant, Requiem aeternam (Figure 5). Plainchant is a body of monophonic song used in the liturgies of the Catholic Church.5 Although the main body of western chant is also referred to as Gregorian Chant, after Pope Gregory I who lived in the sixth century A.D. when the music was popularized, the majority of the plainchant repertoire actually evolved over the course of the Middle Ages, from the 3rd century onward. The Requiem aeternam chant is the introit for the second Roman Catholic mass for the dead: Mass on the day of the Death or on the day of Burial.6 The text, which comes from the apocryphal book IV Esdras, sometimes referred to as ‘The Apocalypse of Esdras’ is a prayer for peace for the deceased (Liber Usualis 1807).7 It reads as follows;

Requiem aeternam dona eis Domine: Rest eternal grant to them, O Lord,

et lux perpetua luceat eis. And let perpetual light shine upon them.

Te decet hymnus Deus in Sion, A hymn befits thee, O God in Zion.

et tibi reddetur votum in Jerusalem: and to thee a vow shall be fulfilled in Jerusalem.

exaudi orationem meam, Hear my prayer,

ad te omnis caro veniet. for unto thee all flesh shall come.

Requiem. Rest. (Jeffers 64)

Figure 5: Requiem Plainchant

Rhetorical Intent- Anachronism and Muffled Meaning

Anachronism, used as a dramatic device, is not a recent phenomenon. Aristotle identified what is widely believed to be anachronism in his Poetics as ‘an instance of improbability,’ especially as it occurs in dramatic productions. For the purposes of the rhetorical exploration of anachronism in this article, we will be defining the term as Merriam Webster does: ‘an error in chronology, especially a chronological misplacing of persons, events, objects or customs in regard to each other.’ Significantly, Aristotle does not disparage anachronism’s use, and anachronism as a rhetorical device appears throughout Greek drama, presumably accepted by contemporary Greek audiences and playwrights well aware of the reality of the historical situation being dramatized. In fact, anachronism frequently serves as an indicator of the drama’s heroic setting; situating narrative components ‘out of time’ encourages an audience to ascribe special significance to the scene. Anachronism, like all rhetorical figures, works best when it contributes to, not detracts from, the successful conveyance of an idea.

Aeschylus in The Persians constructs a democracy for the city of Argos, a distant, heroic realm. Democracy was unique to the Athenian state in which the play was performed, and its audience would certainly have recognized it as such: an imposition of contemporary events and culture onto a dramatic rendering of documented past events. By engaging this anachronism, Aeschylus simultaneously validates the fledgling democratic political structure and imparts upon Argos a laudable similarity to Athens.

Famously, too, many Greek dramatists depict their illiterate heroes of ages past sending and interpreting messages in a written form, which the emerging literacy of the ancient Greek audience would have understood as a detail conflicting with the actual circumstances of the setting. P.E. Easterling, in a 1985 article written for The Journal of Hellenic Studies, concludes that ‘it is part of the imaginative design by which... [a text] is made to seem heroic and homogenous while at the same time reflecting the present-day concerns of contemporary Athenians’ (Easterling 1). In other words, anachronism was not, in ancient Greece, actually at odds with the structure, purpose, and reception of theatrical events. Instead, it is deliberately employed to enhance the performance’s themes.

Anachronism continues in all manner of dramatic forms, from Shakespeare’s inclusion of a chiming clock in Julius Caesar to Queen’s We Will Rock You opening the 15th century setting of the 2001 Heath Ledger film A Knight’s Tale. These anachronistic elements can (and do) elicit accusations of sloppy writing or inattention to detail, but theorists beginning with Aristotle will point out that dramatic historical productions are intended for an audience living in the author’s present. To best convey their message, then, authors must necessarily speak the language of their audience, giving that audience elements that it can recognize and grasp onto—or recognize as out of place.

Twenty-first century television relies equally on the visual and aural faculties of its viewers, who also have at their disposal, as audiences in past decades did not, a multitude of ways of determining the veracity of the representation of a given time or person. Television transmits layers of meaning and multiple messages not only in the narrative content, but through features such as the airing time and the broadcast station framing the program. Neglecting to interrogate artistic and logistical choices flattens what might otherwise be a richly textured and nuanced audience experience; by treating disruptions in viewing expectations as impositions that detract from a program’s integrity, audiences potentially silence voices and repress narratives or themes beneath the surface of the television spectacle, in essence muffling the complexity of the situation portrayed.

Of course, there are instances in which anachronistic features of a television show are inadvertent and cannot be considered to lend meaningful layers to a given program—except to reinforce that fallible human beings are guiding the creation of the show. Consider, for instance, the ‘Goofs’ section found for entries on the online Internet Movie Database (IMDB.com). This site, relying on content contributed by viewers, solicits and displays under the heading ‘Goofs’ ‘Anachronisms’ and ‘Factual Errors’ (the line between the two is unclear). For the first episode of The Borgias, the anachronistic ‘Zadok the Priest’ is addressed — but so is the presence of Cesare’s (François Arnaud) Capuchin monkey, the colour of Rodrigo’s (Jeremy Irons) garments, the colour of the ‘holy smoke,’ and the kissing of the papal ring as the deceased pontiff lies in state. However, no commentary appears about why these anachronisms, none of which undermine the intent or themes of the narrative, might have intentionally been included.

As we have argued, anachronism historically has not been perceived as a rhetorical flaw or fallacy. Rather, employing the audience’s logos — their pre-existing knowledge of the setting of the drama -- and what does not belong in that setting -- acknowledges the role of the viewer in co-creating the experience alongside the writers, production team, and actors, and encourages viewers to explore multiple layers of meaning. Most television and movie music appeals to the pathos of the narrative, contributing to the viewers’ feelings toward the characters and events. The use of anachronism, because it primarily produces a sense of surprise and disturbance in the viewer, can serve as a knowing wink, a shake to wake up the viewer, or a commentary on the unfolding events. However, it is up to the viewer to speculate as to why the anachronistic choice was made to fully comprehend its implications.

Contemporary television consumers have a craving for ‘authentic’ programming. In an article in The Journal of Consumer Research, Randall Rose and Stacy Wood explore the experience and motivation of television viewers watching reality television. ‘Authentic’ things, according to Grayson and Schulman, ‘have a factual, spatial connection with the special events and people they represent’ (Grayson and Schulman 17). After investigating the perceptions and reflections of a multitude of reality TV consumers, Rose and Wood conclude that, counter to appearances, writers and producers are not the sole creators of a program’s authenticity, but that ‘we accept as authentic the fantasy that we co-produce’ (Rose and Wood 296). However, when a writer interjects an element at odds with the perceived ‘authenticity’ of the television programming, a richer viewing experience can be achieved by grappling with the meaning behind that choice than by abruptly dismissing it as ‘inauthentic’ and disruptive.

Consider, for instance, the notoriously detail-oriented Matthew Weiner’s Mad Men. In an article published in June 2012 in The Atlantic, Charlie Wells examines Weiner’s use of a historically inaccurate Burt Bacharach song in the premier of the show’s fifth season. Wells admits that Weiner tends to be slavish in his approach to the show’s historical setting, but that he does occasionally deviate from that approach. When Weiner does, the song choices are revelatory, should the audience choose to accept the music as just as ‘authentic’ as any of the other set pieces bolstering the narrative’s verisimilitude. After all, this is television; audiences are tuning in to experience a deliberately crafted fiction.

The anachronisms in The Borgias are the responsibility of both writer and audience: a moderately well-educated viewer finds jarring Zadok the Priest’s Baroque and English incursion into Renaissance Italy, but it is only when the viewers interrogate superficially ‘authentic’ elements of the dramatic production that the possible implications of the intrusive anachronism become clear. The accessibility of these ‘muffled’ messages is indicated in the pilot by the set location of the music; the subtlest anachronisms occur in closed spaces dense with symbolic ritual performed by the select few. However, comprehending the messages embedded in the anachronistic musical texts reveals to an astute viewer other messages obscured beneath shiny, tightly controlled surface appearances.

Understanding the context of the majority of these musical compositions, especially the Gesualdo and the plainchant, is itself a demanding endeavour, necessitating not only a background in music history and political history, but also a facility for understanding Latin. Because of the peculiar difficulty in identifying both the anachronistic qualities and the original meaning of the historical music in The Borgias, an additional layer of rigor is forced upon the curious audience, and their logos is deeply engaged.

O Vos Omnes, the careful viewer may conclude, is an appropriate anachronistic choice on a number of levels. The work is used to set a scene wherein Pope Innocent VIII is on his deathbed. Its derivation from the Holy Saturday service reflects the interspace, the period of waiting in between dramatic events: in the music’s case, the space between is the death of Christ and his resurrection, and in The Borgias, it constitutes the passage of power from one pope to the next-- but it also suggests a growing darkness, given the extinguishing candles implied in the work’s liturgical setting, at odds with the purifying hope for the Roman Catholic Church verbally promised in the same scene by Rodrigo Borgia. Subtler implications of the scene are further revealed as the piece’s text is examined alongside its original context. As mentioned, Jeremiah, in this piece, mourns Jerusalem’s fall and inevitable captivity, and even though his words, ‘behold my sorrow,’ could be applied to the emotions of the mourners around the bed of the dying pope, a more apt interpretation suggests that Rome herself is about to go the way of Jerusalem, falling and becoming subject to outside forces - not Babylonians in this case, but, rather, a Spaniard.

O Vos Omnes occurs during a scene that is private and guarded: the bedchamber of a dying pope. Certainly not many are permitted into a pope’s bedroom under ordinary circumstances, but when the pontiff is so near his audience with God, the space becomes increasingly privileged. The figures surrounding Pope Innocent VIII are, then, highly favoured cardinals; Rodrigo Borgia is among them. The knowledge held by these figures about the sacred mysteries of the Church and the personal and political machinations underlying her functioning is of the most private sort. These men are the few who could rationally anticipate and subvert the corrupt pontifical regime of the Borgia family. An audience member of the show, too, in order to fully appreciate the gravity of the situation, to grasp the meaning in the exchange of power, must have privileged, personal knowledge of Church history and tradition and the Borgia reputation. The necessity of this knowledge is emphasized, with a nod, in the anachronistic musical choice. Notably, the viewer must work very hard in order to hear the music underlying the dialogue. This obscurity forces the viewers to experience first-hand the closed, tightly guarded nature of the knowledge held by this space. It also bears mention that the piece is obscure even for many musicians: the composer is much better known for his madrigals than for his sacred compositions.

Jerusalem, surge, is again a Holy Saturday piece, and it occurs twice in The Borgias, both in semi-public/semi-private settings. The first instance is Rodrigo Borgia’s first public address to Rome as pope-elect and the second instance is Rodrigo’s official coronation as Pope Alexander VI. Both of these scenes feature physical movement between interior and exterior space. The text of the anachronistic piece reflects partial, partly interior and insightful and partly superficial and ignorant, understanding of the complex narrative situation at hand. When the piece first commences, Borgia is dressed in the garments of a pope privately within the bowels of the Vatican, transforming him visually, at least, from a cunning, power-starved, foreign cardinal to a glorious, holy pontiff. Jerusalem, surge continues with his passage along a hallway, until he eventually stands at a balcony and addresses the worshipful throng below. Borgia is presenting his new public face for the first time.

Contrastingly, the second instance of Jerusalem, surge occurs as Rodrigo Borgia passes from his outdoor procession into the Cathedral. This physical movement will legitimize, making spiritually and materially real, Borgia’s public face, no matter how false it might be. Borgia certainly looks authentic, performing all of the correct movements, receiving the papal tiara, and humbly accepting the blessing of the church. In the eyes of the throng, and, by proxy, of the television audience, Borgia is legitimately pope and his actions ought not be further scrutinized. Of course, the twenty-first century television consumers have the benefit of hindsight—and the salacious Showtime previews of the program— but even if they have no understanding of the future of the Borgia dynasty, the anachronistic score that accompanies these scenes makes a clear comment on the complicated truth behind the appearances.

The music’s text does not reflect a personal sorrow, as does O Vos Omnes, but instead the potential sorrow of an entire city since it implores, ‘Arise, O Jerusalem, put off your garments of rejoicing; cover yourself with sack-cloth and ashes... Let your tears run like a river day and night.’ The implications of this choice are fascinating: to the uninformed viewer, and the uninformed 15th century Roman, the ascension of Borgia to the papacy is entirely fitting, just as the music is. However, when the public, or the viewer, acquires the knowledge of what the text is actually saying, the scenes take on an ominous cast. The writers conflate Rome with Jerusalem, a deliberate and arguably ironic choice given the charged history between the two cities, while simultaneously making a commentary about a beautiful appearance masking a distorted, dangerous reality. The text’s mention of ‘sack-cloth’ reinforces the deceptiveness of Borgia’s papal garments and the grand visual spectacle of the processions and rituals that the pilot episode depicts.

Understanding the sensational history of Carlo Gesualdo further presages the fate of the Roman Catholic Church under Borgia leadership. Gesualdo’s similar descent into a vortex of revenge, intrigue, and murder and the peaceful, holy music he creates seem as diametrically opposed as Rodrigo’s black spirit to his white papal garments. In addition, Gesualdo’s family held strong sympathy for the French and antipathy for the Spanish, adding yet another layer of irony to his compositions’ use in the program (Bianconi 776).

Zadok the Priest is, of course, the most anachronistic of the pieces in the program, and the blatancy of its placement indicates for the audience the weight and complexity of the scene. Handel’s work occurs as Rodrigo, as much a Spaniard to Rome as the German George II was to Great Britain, is processing down the streets of Rome to St. Peter’s Cathedral on the way to his coronation. The anthem begins to play under a character’s spoken inventory of the material wealth necessary to produce the spectacle of the procession, and it continues playing in the background as Rodrigo’s mistress and mother of his children, Vanozza, and his son, Cesare, borne in a brocaded carriage, converse. Cesare observes, ‘You look beautiful, Mother, but you must try to remember that you’re not in mourning.’ His mother replies, cryptically, and in keeping with the musical texts of Jerusalem, surge and O Vos Omnes, ‘But perhaps I am.’ Cesare clarifies, ‘You’re mourning your family, the life that you’ve lived.’ ‘But what are we gaining?’ Vanozza asks. Cesare responds, hesitantly and sceptically, ‘The future.’ The camera then cuts to Rodrigo Borgia looking grand and almost otherworldly, elevated high on a carriage, as the crowd on the street must have seen him, as uncorrupted and above the clamour of material concerns and reality. Significantly, following the perspective from the ground level, television viewers are afforded a glimpse of the crowd scene from Borgia’s own perspective as the singers of Zadok the Priest command, ‘Rejoice.’ The use of the ‘rejoice’ is ironic as well, since, of course, Rome has every reason not to rejoice in a corrupt, rapacious, and murderous Holy Father.

The use of this particular, startlingly anachronistic piece can be interpreted a number of ways, but an interesting approach is its traditional association with the ascension of secular British monarchs. According to the precepts of the Church of England, since the time of Henry VIII, the head of the country is also the head of the Church of England, but this only became so after the Reformation, when Henry, and Great Britain along with him, rejected the supremacy of the Vatican and the Pope. Critics of the Roman Catholic Church cited, in keeping with the Renaissance humanist spirit, the corruption of the Church and its essential wrongness of its insistence that God can only be reached with the facilitation of a priest. Therefore, its use in a scene conveying the crowning of a pope is ironic and complicates the apparent primacy of the Holy See.

The text, in another meaningful layer, references the crowning of Solomon of the Old Testament, the son of David and Bathsheba, renowned for his wisdom and hailed as a prophet. The parallels between Solomon and Rodrigo are rife: both inherit a mighty throne and both are notably intelligent and shrewd. However, Solomon’s eventual decline into idolatry and blasphemy is not yet evident in the statuesque, stylized image of Borgia, but listening to the music, digging beneath the surface of the anachronism, foreshadows Borgia’s sinful future, as well as his place in the stories and legends of the age.

The final historical work, the plainchant, occurs when Rodrigo Borgia has been given the papal tiara. Two of his children, Cesare and Lucrezia, speak about the changes in their identity that must inevitably occur as a result of their father’s coronation. What should be a moment of rejoicing in the new status is instead accompanied by a requiem chant, exhorting God to grant rest to the presumed dead. The ominous nature of an ostensibly restorative occasion, as Borgia vowed to give new life to the Catholic Church, is, through the music, not only implied but flatly stated. The Borgias would go on, both in history and on cable, to poison, murder, fornicate, and scheme through their lives, leaving a long trail of corruption and death behind.

Interestingly, some of the pieces are not only heard in the scenes, but their performances are witnessed by the viewer, further emphasizing the Roman public’s unspoken or obscured knowing acceptance of the Borgia papacy’s corruption; the mood of the pieces seem appropriate and the performances earnest, but the underlying message is at odds with the surface appearance. For instance, as Jerusalem, surge is heard as Borgia is being crowned, the camera captures a choir singing, and during the grand procession, trumpets are raised to correspond with the fanfare in Zadok the Priest.

The historical music on The Borgias, this small study suggests, is inherently palatable and fitting, until a viewer digs beneath the surface, examining the context from which the elements, including the music, making up a dramatic spectacle emerge. Additional, significant layers of meaning can be discerned through personal, individual engagement, investigation, and acquisition of knowledge. Anachronisms in The Borgias subtly but strongly make the case for questioning the palatable surface of spectacle, be that spectacle the ascension of a new pope or the historical music of an expensive cable television drama.

We occupy a moment when complex communicative surfaces abound-- the internet, through social media, television, film, magazines, and online publications, to name a few-- but so does the opportunity to peer past appearances and understand the meaning of the objects and people that make up what entertains us. Engaging our logos, alongside our pathos and ethos, as the construction of The Borgias demonstrates, yields a far more interesting, rich, and compelling experience than simply accepting as truth the face of what we are given.

Notes

1 Morris came to the project with a well-established resume, having had a great deal of experience and success as a soundtrack composer for period dramas. Prior to his work on The Borgias, Morris worked on programs such as The Tudors. His music for The Pillars of the Earth earned him an Emmy for ‘Outstanding Music Composition for a Miniseries, Movie or A Special (Original Dramatic Score)’. His music for The Borgias has proved to be equally successful, earning him a fourth Emmy Award nomination, this time for ‘Outstanding Original Main Title Theme Music’.

2 Alfonso II was the grandson of Rodrigo Borgias’ daughter Lucrecia by her third husband, Alfonso I

3 This setting for six voices (SSATTB) was predated by another that was scored for five voices (SATTB), published in 1603.

4 Five the ten boy sopranos in the chorus had recently been dismissed due to their voices changing. For that reason, the canto parts may have been supplemented by some Italian sopranos from Handel’s opera company. Further compounding the issue was the performers’ disbursement on two specially erected galleries, designed to increase space for the larger-than-usual number of performers as well as guests. The sight-lines between these two galleries were interrupted by the altar. Performers who were unable to see may also have been further confused by two, alternate orders of service that had been circulated.

5 Consisting of a single melody line without harmony.

6 Information on the Roman Catholic liturgical calendar can be found in The Liber Usualis with Introduction and Rubrics in English. The Benedictines of Solesmes, eds. Tournai, Belgium: Desclee & Co., 1952. Print.

7 Esdras was a Jewish ‘Second Moses’ who is credited with the organization of the synagogues as well as with contributing to the determination of which books would become Jewish canon. However, IV Esdras considered to have been written by two anonymous Jewish writers working in the first and third centuries, respectively. (Ron Jeffers. Translations and Annotations of Choral Repertoire, Volume 1: Sacred Latin Texts. 1988: Corvalis, OR, Earthsongs., 64.)

Works Cited

‘Anachronism.’ Merriam-Webster Online. Web. 4 January 2013.

Bianconi, Lorenzo. ‘Gesualdo, Carlo,’ New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Volume 9. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

‘The Borgias.’ Internet Movie Database. Web. 4 February 2014.

Easterling, P.E. ‘Anachronism in Greek Tragedy.’ The Journal of Hellenic Studies 105 (1985): 1- 10.M

Grayson, Kent and David Schulman. ‘Indexicality and the Verification Function of Irreplaceable Possessions: A Semiotic Analysis.’ Journal of Consumer Research 27.2 (2000): 17-30.

Jeffers, Ron. Translations and Annotations of Choral Repertoire, Volume 1: Sacred Latin Texts. Corvalis, OR: Earthsongs, 1988.

‘Jerusalem surge et exue.’ Choral Public Domain Library. Web. 4 February 2013.

Rose, Randall and Stacy L. Wood. ‘Paradox and the Consumption of Authenticity through Reality Television.’ Journal of Consumer Research 32.2(2005):284-296.

The Liber Usualis with Introduction and Rubrics in English. Ed. The Benedictines of Solesmes. Belgium: Desclee & Co, 1952.

‘The Poisoned Chalice.’ The Borgias. Showtime. 3 April 2011. Television.

Wells, Charlie. ‘Mad Men Is Set In The ‘60s, So Why Does It Use Music From Today?’ The Atlantic. 2012. Web. Accessed: 4 January 2013.

Email: luminary@lancaster.ac.uk