Issue 4: Hidden Voices

Ridley's Key: The Forgotten Influence of Joseph Losey in Blade Runner

Vincent Joseph Noto

Not long ago two seemingly unrelated items in film news garnered a good deal of media attention: success and popularity of the film Sarah’s Key (2010)1 and Alcon Entertainment’s announcement that Ridley Scott will do a prequel or sequel to Blade Runner (1982).

Sarah’s Key

As for the first of these items, the success of Sarah’s Key made painfully clear the public’s forgetfulness, not only of Holocaust history, but also film history. Sarah’s Key reveals a subtle conspiracy, especially among the French, to bury or tacitly agree to ignore the unpleasant memory of France’s complicity—albeit under great duress—in La Rafle du Vel d’Hiv.2 The grisly, if somewhat heavy-handedly melodramatic, metaphor of the brother locked away, but inescapably not forgotten on a psychological level, represents well the horrors of suppressed memory on the national, perhaps international, conscience. Though in the end Sarah’s Key won no Academy Awards, the film’s popularity and commercial success brought excitement and praise, but many had to remind the general public that this dark event in French history had been addressed on film before, namely through Joseph Losey’s Monsieur Klein of 1976.3

Losey’s Monsieur Klein met with much criticism in its day but nonetheless managed a Cannes Film nomination in 1976. Its reputation has been improved in some critical circles, much as the majority of Losey’s artistic output has been rehabilitated. For example, The Guardian’s David Thomson extolled Losey’s merits as director and urged that we remember him on what would have been his 100th birthday in June of 2009 (Thomson). In that article Thomson praised a trove of Losey’s films, including Monsieur Klein. Thomson wrote that ‘In Britain, [Losey’s work]… now stands at the head of lines of work by John Schlesinger, Lindsay Anderson, John Boorman, Stephen Frears and so on.’

Despite a continued interest in Losey’s films in the UK and within academic circles, Losey’s films enjoy a nominal following in the US. The blacklisting of Joseph Losey during the Red Scare actually succeeded, in its rough way, even with the passage of what should be more enlightened time, to keep Losey from blossoming fully in the US.4 Perhaps blame lies on another dark part of history too easily forgotten.

Still, the influence of Losey on cinema history, as David Thomson seems to suggest, can also be measured in the works of contemporary directors who make use of Losey’s images in powerful allusions for the purpose of developing their own themes, characters, or even driving the action of their plots. It is a truism that the success of the student complements the master. And indeed, it is in the popular works of the British director and student of film history, Ridley Scott that we find the influence and admiration of the master, Joseph Losey, most fully epitomized. An editorial comment from the Irish Times concerning Prometheus (2012), Ridley Scott’s prequel to Alien (1979), confirms Scott’s continuing interest in Losey’s films:

Fassbender, who plays an android, explained that, while preparing for the role, Scott had pointed him towards the great Joseph Losey picture The Servant. (Clarke)

The careful observer of Blade Runner should not be surprised by such direction from Ridley Scott. Indeed, careful examination will reveal that Scott imbeds or layers tropes, codes, and motifs from Joseph Losey films as various as Monsieur Klein, The Damned (1963), The Boy with the Green Hair (1948), Modesty Blaise (1966), Time Without Pity (1957), and M (1951)—Losey’s American adaptation of the Fritz Lang classic—into Blade Runner. Furthermore, careful examination will also reveal that, in fact, these allusions to Losey’s films lend their thematic content to further enrich Ridley Scott’s already meaningful narrative, subtext, and mise en scéne; and by so doing reassert Losey’s place in film history.

Background and Introduction

Ridley Scott, who honed his skills in advertising, in British Television, and in making the tightly budgeted film The Duellists (1977, with limited US release), rose to fame by directing the science fiction films: Alien (1979) and Blade Runner. Losey too made a brief foray into the science fiction genre, loosely adapting H. L. Lawrence’s novel Children of Light (1960) for Hammer Films in his cult classic, The Damned. Regarding The Damned, it has even lately been said that ‘the thematic contrast between the impulsive, interpersonal violence of Reed’s Teddy Boy character [King] and the chilly, authoritarian violence of Knox’s government functionary [Bernard] is echoed in Kubrick’s 1971 film, A Clockwork Orange’ (Kehr). I think it doubtful this echoing went unnoticed by Ridley Scott, who has been known to emulate and revere Stanley Kubrick to whom, after all, he had gone to for the controversial recycled footage tacked on to the end of the original Blade Runner (Clarke 2002 77).

These themes of troubled adolescent self-image and rage might be compared to the cold‑hearted government and corporate interests and be inferred to have correlative elements in Blade Runner. In such a reading the Replicants could roughly correspond to the angry and violent youths and the blade runners, cops, and corporations—like Tyrell’s—represent governments with their scientific accomplishments serving the established military-industrial complex. But in the works of Ridley Scott other more visual elements common in Losey’s films and, perhaps, more incontestable, may be discovered.

A Tangential Case: Losey in the Futuristic Apple Ad

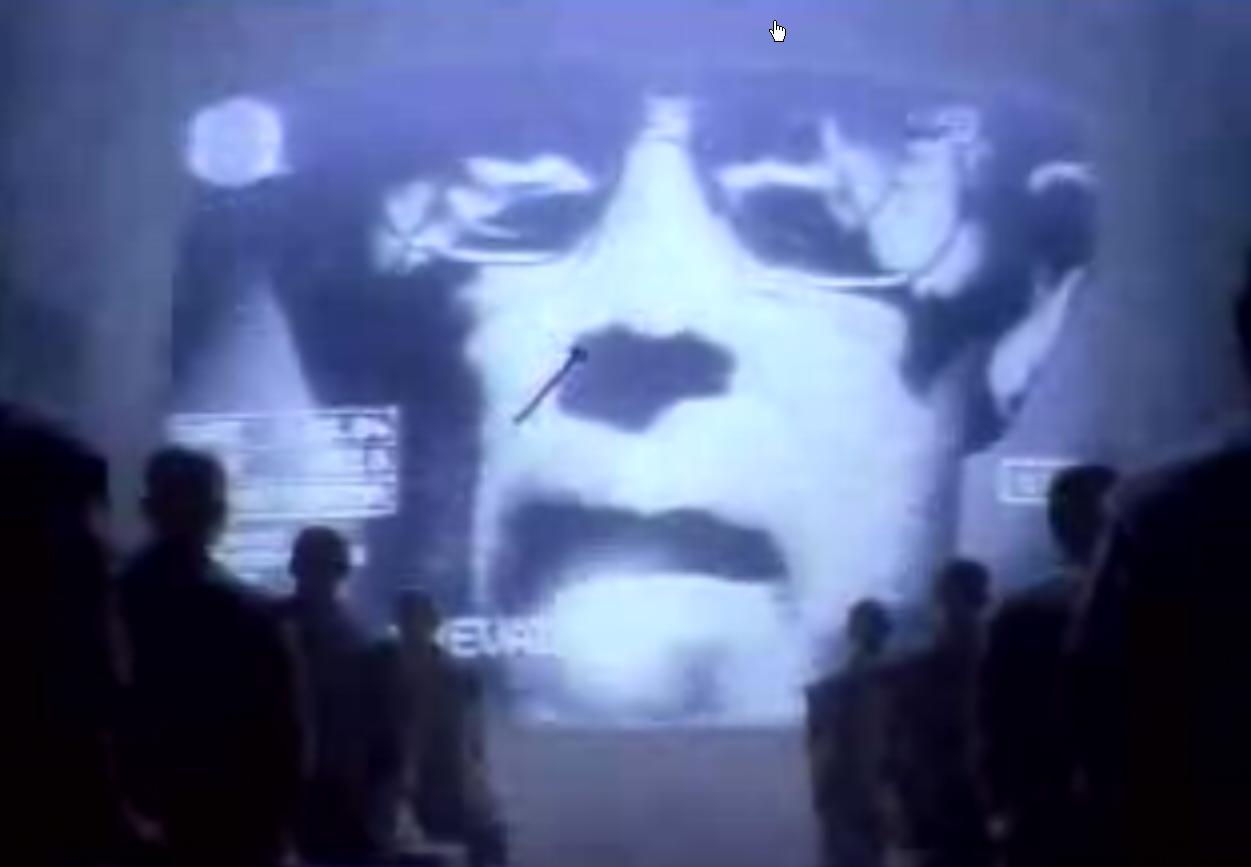

Before we delve further, examining the influence of Joseph Losey in Blade Runner, let us first inspect a tangential case in order to better understand the kind of borrowing we should expect to see. Ridley Scott’s infamous and futuristic 1984 Super Bowl Sunday ad for Apple Computer, Inc., created just two years after Blade Runner, provides an excellent example of Scott borrowing from Losey and illustrates the kind of allusion and homage this analysis will explore.5

The ad depicts a grey version of the future world described in George Orwell’s 1984 (1948) and leads us to a movie theatre with the image of a dogmatist spanning the screen. A tall blonde woman in white and red, looking rather like the model of an Aryan out of a Leni Riefenstahl documentary, carrying a large hammer enters the theatre filled to capacity with drab, grey uniformed workers like those of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927). She spins, and then hurls the hammer, Olympic style, toward the gigantic screen shattering it. Though the Apple ad campaign is purportedly advocating independence and originality, ironically an antecedent to this Apple Macintosh ad scene may actually be found in Losey’s The Damned, which features the story of radioactive-immune children in school uniforms, bred in high government and military secrecy, in a movement of juvenile upheaval and rebellion. While his fellow students fling paste, smear paint, and cover over observation cameras, one of the boys hurls an inkwell, like Martin Luther’s inkwell toward the devil, at the large screen and the two-way camera of their authority figure, their ‘teacher,’ who is actually a military commander of high rank.

Figure 1: Charles (John Thompson) slings his inkwell at the devil camera.

Figure 2: Classroom, The Damned, 1963.

.jpg)

Figure 3: Ad for Apple Computer, 1984.

Figure 4: futuristic theatre.

A similar scene exists in Stanley Donen’s Saturn 3 (1980) —another of Scott’s influences— in which Kirk Douglas does the hurling. However, Ridley Scott expands the size and scale of this trope. He adds an explosion to the screen upon the hammer’s impact and shows its audience in a near gale-force wind, outdoing both of his predecessors to make a surprisingly stunning image of opposition to authority in the face of placid acquiescence and conformity.

Parental Photographs

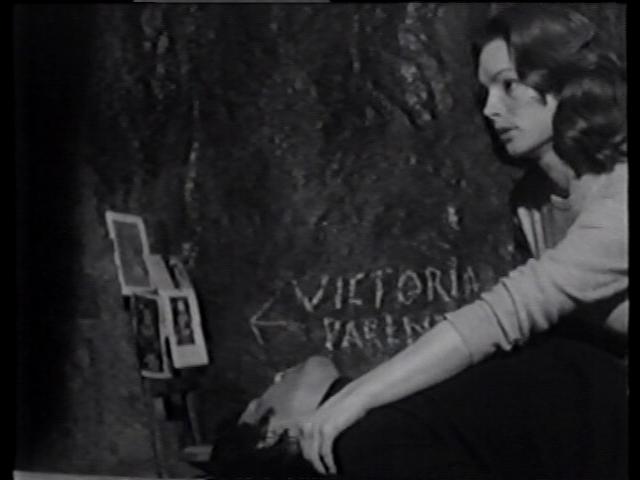

Ridley Scott does a similar kind of visual borrowing from Joseph Losey’s The Damned for his film Blade Runner. If one were looking for shared imagery (in this case mise en scène) between the two films, one could cite the presence of a unicorn. In The Damned the monument and unicorn-statue hangout of King’s Teddy-Boy-like gang, seen early on in the picture, compares vaguely to various unicorn references in Blade Runner. But more persistent and thematically significant is Scott’s use of photographs, modelled after The Damned. The Replicants of Blade Runner obsess over their photographs. They seem to believe the photographs demonstrate that they are real humans by showing their early life, especially scenes of them with their parents. This motif is remarkably reminiscent of scenes depicting the pictures and photographs with which the radiation-immune children of The Damned have plastered the walls of their ‘hideaway’ cave. They too are obsessed with their parents and photographs or images which might depict their likeness.

Figure 5: The Damned, 1963. Radiation exposed King rests while Joan finds the children’s photographs of make-believe parents.

Figure 6: Rick Deckard’s (Harrison Ford) supposed family photographs, Blade Runner.

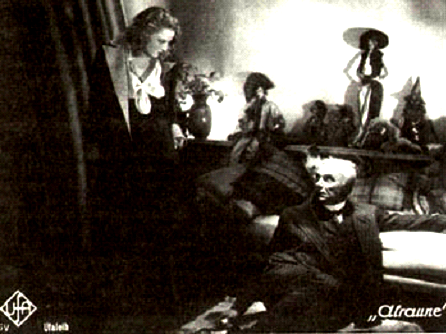

There is a sly thematic link at work here, a motif correlating to many older works of literature and film. This plot element, together with its theme, is shared with theatric and film versions of Goethe’s Faust, with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and its related plays and film and television adaptations, with the film Revenge of the Homunculus (1916),and with Hans Ewers’s novel, Alraune (1911), andits variousfilm reworkings.6 It is a theme related through stories ofextraordinary, even dangerous, children (or beings in fully-formed adult bodies) who are overwhelmed and resentful upon discovering the ghastly secret of their parentage as much as the Replicants of Blade Runner.

Ridley Scott draws upon still another of Joseph Losey’s films for more inspiration along these same thematic lines.In The Boy with the Green Hair, Peter is shocked when another boy lets slip the horrible truth about Peter’s parents and about Peter himself. Before Peter’s hair turns green, we see a scene in the school gym where a clothing drive for war orphans is about to take place. In the gym, teachers encourage the students to display posters of orphaned children. After Peter hangs his poster the following dialogue takes place:

BOY: He looks like you. He looks like you.

PETER: He doesn’t look like me.

BOY: Yes… he does.

PETER: He’s a war orphan.

BOY: Well, you’re a war orphan too.

PETER: I am not.

BOY: Yes you are. We asked Miss Brand where your mother and father was, and she told us they were killed in the war.

Figure 7: Peter (Dean Stockwell) displays his poster in the gym, The Boy with the Green Hair.

Figure 8: Peter with poster of boy ‘like him’ in background.

In much the same way that Peter discovers he is an orphan, the Replicants of Blade Runner find out that they have no parents; indeed, the Replicants find that they are not human at all and are subject to limited life spans or built-in obsolescence. The scene and dialog in Blade Runner bear marked similarities to this scene in The Boy with the Green Hair—including the proximity of a photograph about which the dialog hovers:

RACHAEL: You think I’m a Replicant, don’t you?

Deckard takes off his wet raincoat and throws it on a chair.

RACHAEL: Look.

She goes to him holding a picture in her hand. Deckard looks at it.

It’s an old snapshot, a little girl with a mother.

RACHAEL: It’s me with my mother.

Figure 9: The photo of a girl with her mother—whom Rachael (Sean Young) was programmed to believe was herself. In Deckard’s hand the snapshot appears to come to life for a moment.

From there Deckard (Harrison Ford) goes on to explain that Rachael’s memories are implants, that the woman in the picture is someone else’s mother and that, in fact, she has no mother. Her reaction, much like Peter’s, is one of first denial and then anger.

Furthermore, Rachael’s photo, viewed a bit after the dramatic scene above, appears for a moment to come alive with movement. The shadows of trees on the porch flutter in a gentle breeze, and the mother and child sway ever-so-slightly toward each other. This is clearly another link to Losey’s The Boy with the Green Hair. Indeed, we find that toward the end of The Boy with the Green Hair all the orphans in the poster photographs come to life for Peter in a reverie or surrealistic vision. This was a scene Losey wanted to be of ‘absolute beauty’ but with the actors ‘static and composed in ways that could be related to the war posters in the gymnasium.’ It was a scene Losey regretted for not having gotten quite right without proper budget, animation, or the right special effects team—the kind of team Ridley Scott never lacked in shooting Blade Runner (Losey and Milne 69-70). And for Scott, the photograph became a metaphor for creations or memories appearing real, yet not quite alive as with the Replicants.

Eye and Other Examinations

Since Darwin, our vision and our eyes have become a symbol of evolutionary development. Science-and-philosophy-obsessed Philip K. Dick makes reference to evolutionary theory by use of extensive eye imagery in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968). Ridley Scott faithfully carries this imagery into Blade Runner and adds the ancient image of the all-seeing, all-knowing, and protective eye of Horus through the continued placement of Egyptian iconography. The DVD commentary suggests he is also referencing George Orwell’s Big Brother of 1984. But Dick and Scott also rely on another idea pervasive in Western thought: that the eyes symbolize our empathy and judgment of others through perception, and that we form our concept of ourselves by seeing what lies in the crucible of another’s eye. Translator Benjamin Jowett summarizes Socrates’ explanation of this phenomenon in Plato’s Alcibiades I:‘Self‑knowledge can be obtained only by looking into the mind and virtue of the soul, which is the diviner part of a man, as we see our own image in another’s eye’ (Jowett 9). Centuries after Plato, Guillaume du Bartas would proclaim the eyes as ‘windows to the soul’ and Shakespeare’s Berowne refers to an eye as ‘the window of my heart’ (du Bartas 277; Shakespeare 5:2). Philip K. Dick builds on this symbolism and then alludes to the action of Dr. Gall of Karel Čapek’s R. U. R. (1920),the first drama including android-like creations. In a key scene, Gall searches for signs of humanity in the eyes of the robot Radius (Čapek 67-68).

It is therefore not surprising that this gazing into the eyes in search of emotion or empathic response is Blade Runner’s most prevalent image. Of course the gigantic eye in the introduction and recurring imagery of eyes throughout Blade Runner refer also to Metropolis, Frankenstein (1931), Crime without Passion, (1934),and the playful musical, Just Imagine (1930), but they allude to Losey’s Monsieur Klein andLosey’s M as well. In fact, Losey’s M contains a telling scene in the Bradbury Building—the same building Scott chose to use as J. F. Sebastian’s apartment and for the big Deckard-Roy showdown in Blade Runner. In this building Losey shows an ophthalmologist’s window—with an eye painted on it—being shattered by a thug pretending to be a security guard. One effect is a commentary on the process of viewing a film. The other effect may even have correlative connections—allusory and thematic—to the plethora of shattering glass throughout Blade Runner: Pris’s elbow through the mini-van’s side window, Deckard thrown by Leon against a windshield, Zhora shot as she runs through a series of shop windows, Leon viewed—as he regards dead Zhora—through a glass-winged spinner door, and so forth. Though indeed, in Blade Runner, this breaking glass seems to symbolize something more: the fragility of identity and of life.

Figure 10: The eye shattering motif, from Joseph Losey’s M.

Monsieur Klein also begins with an examination—a rather invasive one. A French doctor measures, prods, and orders about an ordinary looking middle-aged woman He examines and dictates notes concerning her teeth, lips, jaw, nose, ears, lobes, and the pupils of her eyes. Figuratively the doctor’s actions dehumanize the woman. But the purported goal of the examination, a literal interpretation of the text, is clearly the same as the eye exams in Blade Runner: to determine the ‘humanness’ of the individual. It is an evaluation which will establish whether or not an individual is to be treated as less-than-human. In Monsieur Klein twisted Nazi standards of Aryan Master Race decide the outcome. A non-human posing as human in Blade Runner equates with a person of Jewish descent ‘posing’ as a person of non-Jewish descent within the mass of the 1940s German population under Nazi rule in Monsieur Klein. The end result of the exam will ultimately lead to slave labour or extermination in a concentration camp. In Blade Runner the non-humans are enslaved to begin with but, if they return to Earth, they are ‘retired.’ In either case the subjects must first be identified.

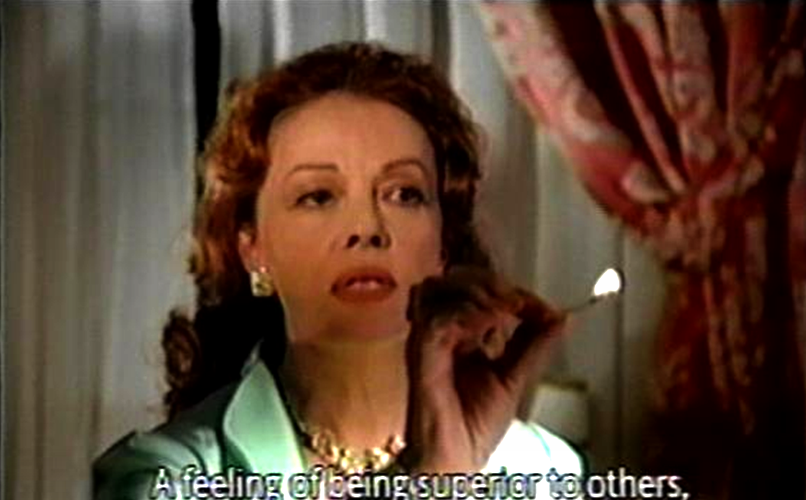

Figure 11: The opening scene of Monsieur Klein. A woman endures a racial examination.

Of course examination of Leon’s eyes, of pupil-responsiveness during provocative psychological questioning of the so called Voight-Kampff test, constitutes the opening scene of Blade Runner.7 The motif occurs again when Deckard gives Rachael a lengthy version of this test. In Monsieur Klein, Losey too dramatizes a second examination—this time of the eyes and lips—in a scene in which Florence (Jeanne Moreau) confronts Klein about his true nature, about his egoism, and about his sense of superiority. She explains that Klein’s double, Robert, makes a game of naming animals to represent people.

Animal Nature

Florence goes on to describe Klein’s animal as the vulture and his doppelgänger’s as the ‘hibernating snake.’ She lights a match and looks carefully at Klein’s eyes. This purposeful lighting of the match to illuminate Klein’s face is closely paralleled in Blade Runner.

Figure 12: Florence (Jeanne Moreau) lights a match to illuminate and examine Klein’s (Alain Delon’s) eyes and face. The images and dialog bare conspicuous similarities to Blade Runner.

Figure 13: Rachel in Blade Runner.

Rachael can be seen deliberately flicking her lighter open just before her Voight-Kampff test. As Rachael lights her cigarette she seems to be manipulating the prospective outcome of her test toward a human result by glancing furtively into the flame of her cigarette lighter, perhaps in the hope that this will open her iris before the test begins. It appears a rather pathetic attempt to confound the Voight-Kampff machine’s result, on the one hand demonstrating she still has doubts about her superiority—in other words, doubts about her own humanity—and, on the other hand symbolically making an allusion to Losey’s Monsieur Klein.

In Ridley Scott’s hands, the animal associations of Monsieur Klein become another opportunity for a cunning bit of allusion. Scott accomplishes this by giving the Replicants similar associations to animals as though they were endangered species in a way that Philip K. Dick never did: Rachael in her feathered coat as owl, Deckard as the unicorn he dreams of, Roy as the white dragon often seen in his background shots, Leon as turtle or tortoise of his Voight-Kampff questions, Zhora as the snake she dances with, Pris as a raccoon like her black-eyed facial cosmetics, and—because early scripts had Tyrell (Joe Turkel) as a Replicant—Tyrell as crane like the design on the curtains in his room. In this way Scott manufactures an allusion to Monsieur Klein. He gives the allusion further credence by tying it to themes present in the original Philip K. Dick novel—endangerment of animal life, real and mythological and biblical, on the Earth. And, in keeping with the rest of his script, he emphasizes that the Replicants should be considered sympathetic characters through these animal associations.

Figure 14: Before the Voight-Kampff examination can be administered, a giant lid-like shade lowers over the ‘eye’ of the bright sun. Symbolically Rachael enters the realm of her own unconscious, a sleeping or hypnotic state where she cannot lie, even to herself.

Examination of the Psyche

Different kinds of associations are also present in Losey’s films and borrowed in Blade Runner. The use of psychoanalysis, psychological testing, word associations, Rorschach inkblot tests, thematic apperception tests, and so forth can be found in post WWII film noir such as Crossfire (1947) or the double or twin-filled Dark Mirror (1946). Indeed from 1940 on, especially toward the end of WWII, the use and popular knowledge of psychology began to spread and had begun to enter the province of cinema (Santos xii). Psychological testing before soldiers entered the war and treatment for shell shock afterwards was also a part of common experience. Psychiatry was just being discovered in this period.

Refugee psychologists coming from Europe came to Hollywood, spread the faith, and so it reached the filmmaker (Friedrich).

Joseph Losey’s remake of M follows this trend of dramatizing psychological tests. He and his screenwriters (including Waldo Salt) add psychological testing of suspects to their version of M which had otherwise been extremely faithful to the originalfilm directed by Fritz Lang. Something very like Losey’s motifof psychological testing becomes the centerpiece of Blade Runner; the Voight-Kampff test of empathic response. Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is a deliberate genre hybrid of science fiction and noir detective fiction. The wave of popular interest in psychology had also caught Philip K. Dick in its wake. His mother had sent him to therapy in 1942 and from this experience Dick became obsessed with advances in psychology and psychological testing (Carrère 7). He tried outsmarting his psychologist’s tests and devising his own tests to administer to his classmates in fun (Carrère 8). In fact, according to Paul Sammon, stumbling across a lack of affect demonstrated in the diaries of certain Nazi concentration camp SS men concerning the cries of children in the night, inspired Dick to write Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (Sammon 16)

Figure 15: In Joseph Losey’s remake of M the police round up the usual suspects and give them psychological tests. Here actor William Schallert portrays a suspect taking a Rorschach Test.

Dick’s novel focused on this lack of affect in certain individuals and created the Voight-Kampff empathy test to fulfil that emphasis. In adapting Dick’s novel it is as though Ridley Scott recalled the effectiveness of Joseph Losey’s incorporation of psychological testing in M and so devised ways in which to make it an integral part of Blade Runner.

Room Searches, Photograph and Mirror Examinations

Provocative questioning, searching the eyes, examining the interior of rooms (metaphor for probing the mind) and rummaging their contents for telltale clues are the stock-in-trade of detectives, of psychologists, and of blade runners. But the scene of Deckard going through Leon’s apartment also has antecedents in other important films, particularly Roberto Rossellini’s Roma, città aperta (1945). In that film, pivotal in the birth of Italian Neo-realism, photographs also bear a strong connection to plot. The scene of the Nazi officer going through Giorgio Manfredi’s (Marcello Pagliero) apartment and bureau drawer bears a striking resemblance to the scene in Monsieur Klein in which Klein inspects the drawers at the apartment of his double. This scene in Roma, città aperta is important because it, and the scenes just after it, have parallels to Blade Runner. In Roma, città aperta, a telephone rings following the drawer-search, and the Nazi answers it pretending to be a friend of Georgio’s, in the same way in which Deckard—brutal and unfeeling as a Nazi—pretends to be an ‘old friend’ of J. F. Sebastian’s when he calls Pris from his police-spinner videophone. With this in mind, we should do well to notice that the hands of the Nazi in Roma, città aperta and of Klein in Monsieur Klein, as they rifle through drawers, are gloved while Deckard’s hand in Blade Runner is not. This is a code of which Losey makes precise use. It is code which Ridley Scott appropriates. In The Damned for example, the gloved hands of military men in radiation‑proof suits who tend the children and the gloved hand of King (Oliver Reed) when he performs his violent, antisocial acts, equate the coldness of the state to that of the sociopath. So, here, Deckard’s bare hand demonstrates that he is beginning to ‘feel’ for the Replicants he is supposed to kill. Indeed he will feel sympathy for Zhora after killing her, and ultimately love for Rachael.

Figure 16: No trench coat here but still perhaps a similarity. The unfeeling, gloved hand of a Nazi SS man goes through Manfredi’s drawer, Roma, città aperta.

Even more striking similarities occur in Blade Runner’s scene of Deckard searching Leon’s apartment. Both Klein and Deckard wear a trench coat—the iconic symbol of the detective and of the warrior returning from trench warfare to a kind of warfare at home.

Figure 17: Pretending to want to rent the apartment, a trench-coated and gloved Klein goes through his double’s drawers.

Figure 18: Blade Runner. Examining Leon’s apartment a trench-coated Deckard finds photographs in a drawer. His un-gloved hands—in contrast to the films above—symbolize that he is beginning to ‘feel’ for the Replicants he is supposed to kill.

Like a detective each is engaged in a bit of self-detection or introspection, namely, ‘How is a Jew any different than me?’ or ‘What is it that makes a man a man?’ In his search, Klein finds a negative to a photograph; Deckard finds a stack of Leon’s photos. Klein takes the negative to a photographer to have it developed and enlarged.

Figure 19: Here Klein, looking rather like a noir-style detective in trench coat and fedora and like the man pictured in the photograph, watches on as a photographer examines the redeveloped print.

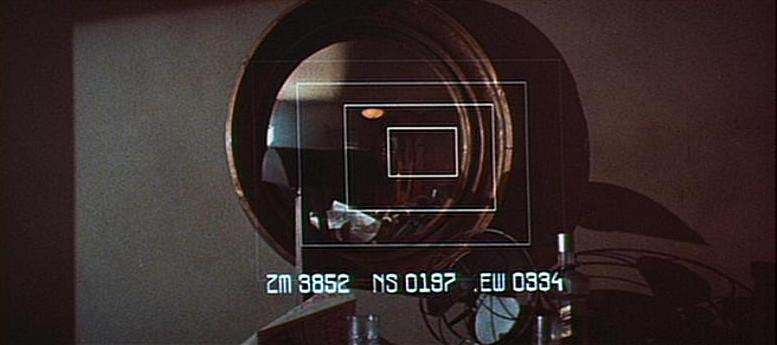

Deckard takes Leon’s photos home to closely examine and enlarge them using his ESPER machine. The scene in which Deckard analyses Leon’s photo, and even more so the photo itself, is yet another reference to yet another Joseph Losey film. Deckard uses a futuristic computer called ESPER to analyse the photograph. The photograph is of a convex mirror against a wall. But the photograph is futuristic so it has greater depth

Figure 20: Deckard uses the ESPER machine to examine Leon’s photo in great detail.

This futuristic photo suggests a kind of high tech version of Jan Van Eyck’s painting The Marriage of Giovanni Arnolfini 8, but at the same time makes reference to the mirror in Losey’s The Servant (1963) or even Modesty Blaise.

Figure 21: Jan Van Eyck’s The Marriage Giovanni Arnolfini

Figure 22: Detail of mirror from The Marriage Giovanni Arnolfini. The window, the couple’s backsides, as well as the artist himself are visible in the convex mirror.

Figure 23: Convex mirror in Joseph Losey’s The Servant (1963). The servants and the masters change roles.

Figure 24: Convex mirror in Modesty Blasie. Modesty (Monica Vitti), at far left, breaks into Paul Hagan’s (Michael Craig) flat.

The significance of this reference lies in the connection between the two film’s themes: servant as master, master as subservient. Roy Batty, even at four years of age, for instance, is clearly superior to the ordinary human, yet he is the expendable pawn in the chess game of his human master and creator, Tyrell.

Identity

As Peter Mayer puts it, ‘an examination of films such as The Servant would reveal that Losey relies rather heavily on the use of mirror shots’ (Mayer 36). Robert Phillip Kolker agrees with Mayer and writes of Monsieur Klein: ‘on a number of occasions when Mr. Klein hears about his double, his first reaction is to glance at himself in a mirror’ (Kolker 380). Peter Mayer also gives a Lacanian-psychology-based interpretation of Klein, and Klein’s habit of mirror glancing, which seems to just as aptly apply to Deckard examining Leon’s photograph of the convex mirror in Blade Runner:

For Lacan, the crucial moment in the life of the individual psyche occurs in the ‘mirror stage’ when the human infant ‘still sunk in his motor incapacity and nursling dependence’ confronts the imago of his own body in the mirror… The subject finds himself engaged in an ever increasing struggle to possess his being, to establish his own identity… In his labour to construct his being for another, he realizes that all his confidence in his newly constituted being is continually under the threat of dissolution, because the other, for whom his being has been constructed, can strip him of his identity. (Mayer 36)

Of course use of mirrors occurs naturally in stories and films involving doubles, including: Edgar Allan Poe’s short story ‘William Wilson’ (1839), Thomas Edison’s film Frankenstein (1910), and the Paul Wegener and Henrik Galeen versions of The Student of Prague (1913, 1926). But Mayer goes on to quote Jacques Lacan describing for the character Klein just the sort of process occurring for the character Deckard of Blade Runner: ‘the subject finds himself ‘caught up in the lure of spatial identification, the succession of phantasies that extends from a fragmented body image to a form of its totality’ (Mayer 36). Undeniably Deckard’s process involves a literal search for fragments of the Replicants—Roy Batty’s (Rutger Hauer’s) elbow, Zhora’s arm—within the frame or other hidden elements of the photograph and then rooting out their full forms. For example in the ESPER analysis of the futuristic photograph scene, Zhora’s full reclining body and tattooed face are reconstructed.

Backstage and the Unconscious

Allusions to Monsieur Klein continue in Blade Runner. Their use conjures mirror images and doublings in other aspects with a variety of implications. We see this when Klein seeks information about the girl in the photograph backstage at a club where female impersonators and other entertainers prepare to go on stage. Here the trope is of actors preparing to play at being something they are not, and of non-women posing as women before a set of mirrors, practicing and evaluating themselves. It is also here that Klein, puts on a mask, so to speak. He behaves here in a false, yet charming, way to get the information he seeks. It is an odd counterpoint to an earlier scene at a club where a skit has a masked actor playing the role of a heavily stereotyped Jew. And so we find a Jew, Klein’s double, posing as a non-Jew in Vichy France. We also find a man—mercenary, acquisitive, insensitive, arrogant, womanizing—our all-too-human Monsieur Klein - posing as a complete human being in a world of Nazi-thinking. These are all actions not unlike those of the Replicants posing as humans.

The idea of this intrusion into the backstage also represents examination of the unconscious mind. How does one regard one’s self? How does one reconcile one’s inner belief to one’s identity with the outward self one sees reflected in mirrors and in the eyes of others? The hypocrisy of Klein, like that of Rick Deckard, becomes apparent to him within his own reflection and self-inspection. Exploiting a Jewish need for fast-cash in a mad political climate to your own absurdly overinflated financial benefit represents the height of hypocrisy and a lack of empathy. So does retiring Replicants when you don’t know what defines you or them as being human. And so it is that the entire backstage scene of Monsieur Klein is imitated in Blade Runner. Again the trench-coated outsider intrudes into the backstage, prying and investigating.

The backstage scenes of Deckard going after Zhora find strong parallels not only in Monsieur Klein but also in Losey’s earlier Time Without Pity. Here images show recovering alcoholic David Graham—this time played by a trench-coated Michael Redgrave—amateur-gumshoeing. Graham, whose son has been found guilty of murder and is sentenced to die, goes backstage attempting to follow up leads to the murder. Under the pressure of time, he finds himself in the absurd situation of trying to cajole or wrest vital information from chicken-costumed dance and chorus girls. Ridley Scott echoes this sequence.

Figure 25: Klein questions a performer amongst a bustling backstage ambiance of circling showgirls and female-impersonators.

The symbolic implication here is implied with a twist. In Time Without Pity, the girls are too chicken to give information. David Graham is afraid time will run out and his son will die for a murder he did not commit.

Figure 26: Time Without Pity, 1957. Amongst the backstage dancehall bustle a trench coated David Graham (Michael Redgrave) seeks information. The showgirls in their chicken hats contrast Graham’s seriousness and desperation.

In Blade Runner a snake—Zhora—slithers among the hens. At this point in the plot it remains to be seen if Deckard himself ought to turn chicken and run. He too has, after all, something to fear a good deal more than Zhora: the fact that he may indeed be a Replicant himself.

Figure 27: Blade Runner. Deckard leans against a neon star. The busy backstage is an allusion to Losey’s films. Note the girl in the chicken hat as in Time without Pity and (a bit out of focus) the girl in the background with the cumbersome headdress not too dissimilar to the one in Monsieur Klein.

Enter trench-coated Deckard probing, questioning the bartender, then trying to appear nonchalant—reading his newspaper as chorus girls in chicken hats shuffle past. Once Deckard finds Zhora backstage, the imagery again becomes remarkably similar to Monsieur Klein. Among the bustle of backstage activity, both Deckard and Klein assume a character and attempt to wring much needed information out of stage performers. Klein pours on the charm and is friendly. Deckard impersonates a Chandleresque, sleaze-ball voyeur pretending to be with the ‘American Federation of Variety Artists Confidential Committee on Moral Abuses.’ Layers of pretending are demonstrated. Zhora too pretends to be human so as to survive. Even Zhora’s snake pretends to be a bona fide reptilian snake. This is a potent aspect of Scott’s allusion to Monsieur Klein. Like Losey, it perpetuates the use of major characters and stage performers as pretenders. Klein pretends to be unaffected by the suffering or exile of Jews from France, or later he pretends not to have a Jewish strain in his family lineage. Deckard goes on killing Replicants, putting off the real question at hand, trying to pretend that he isn’t afraid to confront the possibility that he too is a Replicant.

Through allusion to Losey’s Monsieur Klein and Time Without Pity, Ridley Scott’s frenetic backstage represents the unconscious considering the self, peeling away at outward identity, posing and pretending, and assuming roles in order to prepare to act on the stage of life and in order to survive.

Thighs and Eyes

Eventually Zhora loses patience with Deckard’s act. She attempts to strangle him before witnesses arrive in the room. This scene and the one that follows later when Deckard attempts to ‘retire’ Pris, bears resemblance to Losey’s more popular movie hit, Modesty Blaise, a tongue-in-cheek send-up of spy vs. spy thrillers based on a comic strip (1963) and novel (1965) of the same name by created Peter O’Donnell and Jim Holdaway. If this scenario in Blade Runner seems rather cartoonish consider that Ridley Scott upon more than one occasion has said that he regarded the process of making Blade Runner as much like filming a comic, and that much of the look of Blade Runner was based on comics such as those in the magazine Metal Hurlant (1974-1987, aka Heavy Metal) (Park 57-58).

This film is not a warning in any sense of the word. At the moment I choose not to do films which are loaded in that way. This film is, hopefully, good fun. The films that have fascinated me the most in the last couple of years tend to have been films which are derived from comic strips. I’ve chosen to go in that direction, and therefore, there are a lot of broad strokes, fast, bold action, and colourful characters. (Ridley qtd. in Kerman 151)

Interestingly, Losey described his Modesty Blaise in nearly the same terms:

I wanted to make a film full of fun, full of laughter of various kinds and at various levels, which would at the same time make the amorality of the James Bond films… apparent [my italics]. (Losey and Milne 145)

For all its faults, Modesty Blaise certainly serves as model for one making a film in good fun. But, as with all of Losey’s films, Modesty Blaise also contains serious themes—particularly the brutality and unwavering conviction of the established governments. In Modesty Blaise, only the villains such as Gabriel (Dirk Bogarde) or McWhirter (Clive Revill), and sometimes those in between such as Modesty and Willie Garvin (Terence Stamp), repeatedly question and consider the morality of their actions and the people they put at risk, whereas governments and their minions never do. At lunch self-designated villain, Gabriel, covers his ears as servants sear his lobster in boiling water and says ‘I can’t bear to hear them screaming’, while his right-hand man, McWhirter, sounding at first like Rene Descartes argues: ‘it’s a proven fact that lobster feel no pain; it’s just wind escaping.’ And a few moments later when Gabriel learns of his henchmen’s death in an underwater diving exercise, he says, ‘How can I eat lobster… when the lobsters are eating Borg?’ Blade Runner shares this motif of blurred lines of villainy. The allusions to Modesty Blasie go beyond just ‘good fun’ since Replicants, blood thirsty as they are, are presented more sympathetically than the forces of government aligned with the Tyrell Corporation. Indeed, Gabriel’s boiled lobsters might just as well figure into a Voight-Kampff empathy test question as any patio luncheon debate.

Figure 28: Pris with Deckard between her legs.

A similar scene to the one depicted in Figure 28 also appeared as an action sequence in Modesty Blaise. Mrs. Fothergill (Rossella Falk) murders the clown faced mime, Crevier (Joe Melia), in a scene designed to demonstrate her complete lack of empathy and perverse infatuation with killing for fun. Pris’s cart-wheeling and thigh-squeezing struggle with Deckard seems cartoonish at first too. But the symbolic value of death between the thighs of woman, a reversal of conception and birth, may hint at a less fun, less pop-culture oriented origin. Indeed the image’s nascence might well be in Bertolt Brecht’s introduction to his early play, Baal (1922), which begins:

And that girl the world who gives herself and giggles

If you only let her crush you with her thighs

Shared with Baal, who loved it, orgiastic wriggles.

But he did not die. He looked her in the eyes. (Brecht 20)

Figure 29: Mrs. Fothergill (Rossella Falk) chokes the turncoat mime, Crevier (Joe Melia), to death between her thighs.

Figure 30: This time, it is mime‑faced Pris in Blade Runner that has Deckard at her mercy and between her thighs.

Losey of course, collaborated on a staging of Brecht’s Galileo Galilei, in 1947 and again on a screen version, entitled Galileo in 1975. We do well to note here the rhyming words thighs and eyes in many English translations (though it’s closer to knees in the German), with all their implications for Blade Runner symbology and themes. And so it is that, once again, we find Scott borrowing from Losey: this time for matters of cartoonish action and—somewhat abstruse—matters of thematic enhancement.

Man as Machine in Bertolt Brecht

The origin of the Replicant animal associations we saw earlier in Blade Runner correspond with those of Losey’s in Monsieur Klein. These associations reference endangered species on the earth in modern times and diluvian animals saved (or not saved if we include the unicorn in some legends) by Noah or Utnapishtim (of Summarian mythology) in Western religious traditions (Hathaway 37-38). But these associations in both films also derive from Brechtian sources. As critical filmographer of Joseph Losey, Colin Gardner, points out, the idea of man as machine is one of Brecht’s favourite tropes (215-216). Gardner also mentions the example of auto manufacturer and race-car enthusiast Robert Stanford (Leo McKern), in Losey’s Time Without Pity who:

is able to block out any residues of past guilt by translating the psychological ramifications of sex and violence into purely machine-like metaphors ‘Well, she stood up to it’, he excitedly tells his engineers after testing his new prototype: ‘She took everything I could give her (unlike, of course, the car’s flesh and blood equivalent, Jenny Cole [Christina Lubicz]). (Gardner 50)

This man-machine (or woman-automobile in this case) trope has its analog in the Replicants of Blade Runner. Ridley Scott, according to Paul M. Sammons, said of a half-abandoned idea concerning Roy Batty: ‘We experimented with some tattooing that was supposed to suggest something like demarcations in an engine’ (Sammon 188). So, again, we have imagery suggestive of man as machine.

In his analysis of Losey, Gardner later delves into the Brechtian trope of man or soldier as a perfect fighting machine—for us, another analogous description of Roy Batty and the other Replicants—which occurs in Bertolt Brecht’s Mann ist Mann (1926), a play with themes, significantly, concerning the individual’s loss of identity in modern mechanized society:

In A Man’s A Man (1926, Eric Bentley’s translation of Mann ist Mann), the political clown Galy Gay, a humble Irish porter in Kiplingesque India, is transformed into the replacement soldier Jeraiah Jip, literally a human fighting machine. The play boasts that, ‘Mr. Bertolt Brecht will prove that one can / Do whatever one wants to do with a man: / a man will be reassembled like a motor-car tonight in front of you / And afterwards will be good as new.’ (Gardner 215)

Similarly it becomes clear, if we go back to Losey’s film, Modesty Blaise, that Losey’s assassin/clown, Crevier, is probably the immediate progeny of Brecht’s Galy Gay of Mann ist Mann, however indirectly, and so therefore the clown-faced gymnastic-assassin, Pris, represents Galy’s more distant cousin. But, as Gardener goes on to point out, the animal nature, counterpart to machine nature, of man is also part of Brecht’s formulation. While ‘man-becoming-machine’ is Brecht’s favourite trope of conceptual self-discipline, ‘man-becoming-animal’ is its dialectical counterpart. During the 1947 Hollywood production of Galileo, for example, Brecht wrote a short-story outline, From Circus Life [1938], for the pantomimist Lotte Goslar, the play’s choreographer. This piece describes

a ‘terrible scene’ in a circus when a clown inadvertently finds himself trapped in a lion’s cage. The clown attempts to frighten the lion, but something curious happens—the lion hypnotizes him with a gaze and gradually induces him to perform the very tricks the trained lion had once done. The transformation of man into beast is so complete that when the lion turns its gaze from the clown for a moment, the clown springs on it. Disregarding attempts by attendants to divert him with pistol shots and iron hooks he proceeds to bite the lion to death.

This parable expresses one of Brecht’s favourite political themes, that if one fights a tiger (i.e. capitalism, or the master in a master-slave relationship) one becomes a tiger. Man takes on the characteristics of his oppressors (Gardner 215-216).

This idea of Brecht’s is echoed in the crux of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? After studying Nazis and SS journals, Philip K. Dick made the androids [Scott’s Replicants] metaphors for people with a lack of affect or a Nazi mentality and he envisioned a time when there might be:

a contest to see whether the humans won or the quote androids unquote won. [And then] the problem then would be: Would we become like the androids in our very effort to wipe them out?... Would we inhale a contagion in the very act of trying to abolish the contagious element?... so a further problem is then created—the paradox of if you kill a person, if he is inhuman, do you not then become inhuman in the act of killing him? (Dick in Sammon, 1981)

Ridley Scott adopts aspects of this theme in Blade Runner in the scene where Roy Batty goads Deckard to accept a latent Replicant nature and to be the tiger that he himself is.

Another of Brecht’s characters, of Sergeant Bloody Five of Mann ist Mann, castrates himself in order to maintain focus on his soldiering, paralleling the impotence of the Replicant Leon in Blade Runner who, in some early scripts, lacks the reproductive potency or organs but, even in the Final Cut release (2007), still has ‘an itch’ he can never scratch (Heldreth 313).

Also, if we again take license to include deleted Blade Runner scenes in our analysis—we have near parallels to Galy Gay’s soliloquy at his own coffin. The first occurs when Deckard visits enfeebled Holden in his coffin-like ‘iron-lung’ in a hospital—a scene that was cut from the film but included in the Blade Runner Final Cut DVD extras. The second parallel occurs when Roy Batty visits the coffin of the real Tyrell in a scene that never made it beyond script and sketches—a version in which the Tyrell who gets his head crushed is a Replicant duplicate of the deceased Tyrell.

Finally we have both Galy Gay and Rick Deckard beginning their journey of self‑discovery, at the fish market. In Mann ist Mann, Galy Gay goes to buy a fish and gets accidentally conscripted into the army and ultimately goes to war (Brecht 123). In Blade Runner, Deckard goes to the fish market to find out that a scale he found in Leon’s bathtub is not a fish, but a snake scale, and then he’s off to battle with the Replicants. Both characters begin a journey in which they make discoveries about themselves and the nature of identity.

In referring to antecedents in the films of Losey, Scott indirectly alludes to Brecht. These Brechtian allusions carry myriad codes and thematic links regarding the nature of human identity as animal moving increasingly toward mechanization in modern times. Mechanization programmed, as Sergeant Bloody Five, Galy Gay, or Rick Deckard are programmed, to be the best killing-machines (or blade runner) and to believe whatever those in power wish them to believe. This control goes beyond identity even to invade memory. And so it is that in Mann ist Mann the importance of identity cards is emphasized: ‘Identity cards are such a good thing. The best of us has an imperfect memory’ (Brecht 188). Blade Runner also engages with notions of identity through the manufacture of implanted memories. Through these allusions Scott has cycled back to Philip K. Dick who writes about political control of individual and historical memory in his short story ‘We’ll Remember It for You Wholesale’ (1966), in his outline for a proposed novel Joe Protagoras Is Alive and Living on Earth (1967), and in his philosophical essay ‘Cosmogony and Cosmology’ (1978), to name but a few. It is also clear that Dick had read and been influenced by Brecht (Carrère 27).

The recruitment of Galy Gay to replace Jeraiah Jip in morning roll call, and later as effective soldier, in Mann ist Mann, presents a doubling. Confronting his coffin Galy Gay says: ‘So how could I open this crate? I’m afraid. And who am I? I am a Both: there are two of me’ (Brecht 182). Roy Batty demonstrates how he is Tyrell’s equal—symbolically at least—by besting him at chess. Captain Bryant recruits Deckard as a replacement for Holden after Leon incapacitates and nearly kills him. These represent more doublings.

Though, indeed, it is possible that some of these parallel codes in Blade Runner are unintentional, structurally they are linked nonetheless. At the very least, their geometry, their mise en scène, and their narrative structures contain strong similarities. The presence of a coffin, the proximity of dead or incapacitated perceived doubles, equals, or ready replacements, all work toward a common code of thematic implications reminding characters of the impermanence of identity and of their own mortality.

Figure 31: Deckard confronts his mortality in meeting Holden in his crypt-like ‘iron-lung.’ Holden too has become man and machine: ‘He can breathe okay as long as nobody unplugs him.’

Dolls

Consistent with themes concerned with identity, the characters of Brecht’s play, Mann ist Mann, are prescribed to be masked. In some performances of the play, the characters are mime-faced much as Joseph Losey’s character Crevier in Modesty Blaise. In Blade Runner, Pris uses her mime-like face to pose as a doll among dolls, hiding. Doll imagery is common in many examples of film noir, including the life-size forensic doll of Richard Fleischer’s Follow Me Quietly (1949) and Frennessey March’s doll collection in Robert Aldrich’s World for Ransom (1954). Traditional elements of film noir—high contrast light and dark, shadows, venetian blinds, tilted camera angles,innovativeuse of sound—are passed down from silent films and European expressionist cinema—often by expatriate directors, or other workers in film, themselves. These types of traditions are easily seen in films such as Cabinet of Dr. Cagliari (1920), Nosferatu (1922),and the Dr. Mabuse (1922, 1933) series, to name a few well know examples. So it is not surprising for Joseph Losey to use doll imagery much like the silent and talkie versions of Alraune. The eponymous character, Alraune,is an alluring, cold-hearted woman created through eugenics and artificial insemination experiments. She is also an important prototype of the femme fatales so common to film noir (Pringle 665-666). Losey created a number of films in the noir vein. The colourful Modesty Blaise, made in 1966, is hardly in that category, but does retain this prevalent doll imagery.

Doll imagery is also related symbolically to eye imagery—so much a part of Blade Runner. The Latin pupa is, after all, the origin of the word pupil—meaning the centre of the eye. This is because the tiny mirrored image one sees of oneself in the eye of another was said to be a doll-like reflection of the self. Additionally, in ancient Greece and Rome young girls were traditionally given dolls—adolescent dolls somewhat like a Teen-Barbie doll—which represented their virginal adolescent life. These dolls more than represented them symbolically; they were in fact the girl’s ‘virginal double’ (Bettini 226-227). The dolls were then given up to the goddess Venus or Artemis as part of their marriage rituals on the eve of their wedding. In Alraune and film noir, dolls have a similar function, representing the outward cold and plastic projection of the female objectified and perhaps dead inside. They may also signify the death of innocence as, for example, in the character of the no-longer-innocent, world-weary Frennessy March (Marian Carr) of World for Ransom. This motif involves a kind of paranoia of 1940s men off fighting in wars, troubled about the ‘helpless-without-them’ women they have left behind. Men preoccupied about the kind of independent, left-to-themselves (or other men), women to whom they might return. Doll imagery also signifies sterility, the childlessness of unmarried women. It represents coldness and lifelessness and death generally. Recall that in Joseph Losey’s The Damned the children’s bodies were cold and that when King (Oliver Reed) feels the face of one of the boys he exclaims ‘He’s dead. He’s dead, I tell you!’ The children in The Damned are adorable and doll‑like, yet they represent the lethalness of nuclear warfare. They are in fact, deadly in themselves, projecting their own body-generated nuclear radiation.

Figure 32: Brigitte Helm as Alraune (1928), among dolls and teddy bears.

Figure 33: Helm again as Alraune (1930) with dolls and puppets.

Figure 34: Frennessey March is left alone with only her many dolls for company toward the end of World for Ransom,1954.

Figure 35: Frennessey cradles a girl doll dressed in a man’s suit just like the one she wears on stage.

Losey also peppers Modesty Blaise and M with doll images. The alluring Tina Aumont, portrays doll-like Nicole as helpless, a foil to Vitti’s unflappable, though still doll‑obsessed, Modesty. Similar to this mise en scéne surrounding Nicole, dolls in M convey the vulnerability and fragility of the child victims of child molester and murderer Martin Harrow (David Wayne).

Figure 36: Modesty Blasie (Monica Vitti) holds dolls of herself and Paul Hagan (Michael Craig) in Losey’s Modesty Blaise, 1966. More dolls line the wall.

In Blade Runner the attractive ‘pleasure model,’ Pris (Daryl Hannah), also associated with dolls, is not, evidently, equipped to reproduce children—a theme also explored by Philip K. Dick in his presentation of the android character, Rachael in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? This Rachael asks, ‘How does it feel to have a child? How does it feel to be born for that matter?’(Dick, 1987 169)

Figure 37: Modesty Blaise, 1968.

Figure 38: M, 1951.

Dolls shown in parts or broken, such as the mannequins in M, are codes for objectification and violence against women. But, in the case of Pris from Blade Runner—in one scene holding up a sexually mature, Barbie-like doll, vivisected, lacking her lower half, her reproductive anatomy—the code is one of barrenness, envy, resentment. She’s a Replicant with no childhood playing with a doll, but knowing she will bear no children. Pris is however, like Losey’s Modesty Blaise, better equipped to defend herself physically, having apparently picked up some of Zhora’s ‘Off-World kickmurder squad’ skills.

Other references, similarities, and homages to the works of Joseph Losey can be found within Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. Use of industrial fans, use of plastic, use of mannequins, use of famous poetic interjections in the mist of ordinary dialogue (Losey: Thomas Grey in Modesty Blaise; Lord Byron in The Damned; William Blake in Blade Runner 9), Scott integrates them all. They layer themes, open doors in plot, aid in characterization, and contribute to the film as a whole.

Figure 39: Pris holds up a doll from Sebastian’s collection, which has been vivisected and is lacking reproductive anatomy.

Like the eye through the prison door from Modesty Blaise pictured at the opening of this article, they reflect a self-conscious view. They represent a film ever mindful of its own language, codes, idioms, and clichés—and call out for a kind of self-examination. These allusions and homages to Joseph Losey by Ridley Scott are ultimately complimentary and demonstrate the viability of the Losey legacy in film history. If the general public no longer recognizes or remembers Joseph Losey’s films as they did with Monsieur Klein — created long before Sarah’s Key—then at least some of us will have to sustain Joseph Losey’s memory and ourselves otherwise. Some of us will have to become a little like Deckard with his ESPER machine, detecting fragments of Losey’s thinking and imagery—with perhaps their greater depth of thematic focus—hidden but kept alive, like a haunting guilt or memory, within the works and psyche of some the finest contemporary filmmakers such as Ridley Scott.

Notes

1 The film adaptation of Tatiana de Rosnay’s New York Times bestseller, Sarah’s Key, grossed $21,118,093 world-wide total gross profits: Sarah’s Key (2011) - Box Office Mojo. Web. 22 April 2012 [Accessed 17th July, 2014]; Kristin Scott-Thomas was nominated for the French César Award for best actress for her performance in Elle s’appelait Sarah (original title of Sarah’s Key): Lévesque, François. ‘À voir à la télévision le jeudi 12 avril - Ma soeur, cette inconnue,’ Le Devoir, 7 April 2012. Web. [Accessed 17th July, 2014]

2 Known in English as the Vel d’Hiv Roundup. The Vel d’Hiver Roundup marked its 70th anniversary in July of 2012. The New York Times referred to this anniversary as ‘the latest reminder of a past that resists burial.’ Riding, Alan. ‘When past is Present.’ 20 July 2013. Web. [Accessed 17th July 2014].

3 For an example reminding the public see: Kenneth Turan, ‘Movie review: Sarah’s Key,’ Los Angeles Times, July 22, 2011. Web. [Accessed 17th July 2014] Note also that Monsieur Klein’s 1976 release puts it 19 years before Jacques Chirac’s 1995 speech which is famous in France for being the first public mention of the Vel d’Hiv Roundup since WWII.

4 US Congress approval ratings ‘dropped to historic lows (9 percent, according to a New York Times-CBS poll), which sent wags looking for anything ironic that enjoyed more favourability: [this included] “US going communist” = 11 percent, (Rasmussen poll)’. See: Sullivan, Christopher. ‘In Year of Cataclysms, a few faces stand out.’ The Guardian. 23 Dec 2011. Web [Accessed 14 Aug 2012].

5 The company would not be known as Apple Inc. until 2007.

6 Alraune, c1918—Hungarian silent; Sacrifice, 1918—German Silent; Alraune, 1928—silent (Unholy Love, Mandrake, or A Daughter of Destiny); Alraune, 1930—talkie; Alraune, 1952 (Unnatural).

7'Voight-Kampff test' in the film; ‘Voigt-Kampff Altered Scale, Personality Test, or Apparatus’ in the book, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? In the novel, the term refers less often to the test or machine but to how the results of such a test are interpreted, and it is presumably named for its mathematician inventors (for example: the Voigt Profile named for Woldemar Voigt [1815-1919]). The name ‘Kampff’ is hypothesized to be a reference to Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf and, at the same time ironically emblematic of an individual’s ‘struggle’ within the context of morally provocative questioning, see Joseph Francaville’s essay, ‘The Android as Doppelganger’ in Retrofitting Blade Runner, edited by Judith Kerman. (Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1991).

8See Marie Lathers’ The Aesthetics of Artifice: Villier’s L’eve Future (University of North Carolina Press, 1996, pp. 140-141) for an insightful analysis of The Marriage Giovanni Arnolfini and Leon’s photo in Blade Runner.

9 Thomas Grey’s ‘Elegy in a Country Churchyard’; Byron’s ‘The Prisoner of Chillon’ –a recording of this poem is in the children’s curriculum. It is a poem whose speaker is the last survivor of a family, whose hair has gone grey with shock, and as a prisoner like the children in The Damned, has been one for ‘whom the goodly earth and air /Are bann’d, and barr’d’; Roy Batty’s version adapted from Blake’s long poem, ‘America: a Prophecy.’

Works Cited

A Man’s a Man. Adapted by Eric Bentley from Mann ist Mann by Bertolt Brecht. Produced by the New Repertory Theatre Company. Masque Theatre, Sept. 19, 1962.

Bettini, Maurizio. The Portrait of the Lover. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999.

Blade Runner. Dir. Ridley Scott. Warner Bros. 1982.

Brecht, Bertolt. Baal, a Man’s a Man, and the Elephant Calf: Early Plays. Trans. Eric Bentley and Martin Esslin. New York: Grove Press, 1964.

Čapek, Karel. Toward the Radical Center: A Karel Čapek Reader. Ed. Peter Kussi. New Jersey: Catbird Press, 1990.

Carrère, Emmanuel. I Am Alive and You Are Dead: A Journey into the Mind of Philip K. Dick. Trans. Timothy Bent. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2004.

Clarke, Donald. ‘The Great Prometheus Certificate Debate.’ The Irish Times, 15 April, 2012. Web. 6 December, 2012.

Clarke, James. Ridley Scott. London: Virgin, 2002.

Dick, Philip K. ‘We Can Remember It for You Wholesale.’ The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction. New York: Mercury Press, 1966.

------ The shifting realities of Philip K. Dick: selected literary and philosophical writings. Ed. Lawrence Sutin. New York: Pantheon Books, 1995.

----- Blade Runner: (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, [1968]). New York: Ballantine Books, 1987.

Du Bartas, G. The Divine Weeks and Works of Guillaume De Saluste, Sieur Du Bartas. Trans. Joshua Sylvester. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2012.

Friedrich, Otto. American Cinema. New York Center for Visual History, in association with the BBC and PBS. 1994. Television.

Hathaway, Nancy. The Unicorn. New York: Tess Press, 2005.

Lawrence, H.L. The Children of Light. London: Macdonald & Co, 1960.

Losey, Joseph and Tom Milne (eds.) Losey on Losey. New York: Doubleday, 1968.

Kehr, Dave. ‘Nefarious Doings in a World of Sunlit Decay.’ New York Times, 2 April 2010. Web. 7 March, 2012.

Kerman, Judith. (ed.) Retrofitting Blade Runner: Issues in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner and Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1997.

Kolker, Robert P. The Altering Eye: Contemporary International Cinema. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

Jowett, Benjamin (trans.) and Plato. Alcibiades I and II. Middlesex: Echo Library, 2006.

Martin, James M. ‘Modesty Blaise by Joseph Losey,’ Film Quarterly. 20.4 (1967): 63-65.

Mayer, Peter. ‘Mr. Klein and the Other.’ Film Quarterly. 34.2 (1980): 35-39.

Modesty Blaise. Dir. Joseph Losey, Beverly Hills, Calif: 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2002.

Park, Jane C. H. Yellow Future: Oriental Style in Hollywood Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Pringle, David. St. James Guide to Horror, Ghost & Gothic Writers. Detroit, MI: St. James Press, 1998.

Sammon, Paul M. Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner. London: Orion, 1996.

Sammon, Paul M. ‘Interview with Philip K. Dick.’ 1981. [My transcription]. Blade Runner: Enhancement Archive (disk four), Inception (chapter), from Blade Runner: Four-Disk Collector’s Edition. Dir. Ridley Scott.

Santos, Marlisa. The Dark Mirror: Psychiatry and Film Noir. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2011.

Scott, Ridley. ‘Audio Commentary.’ Blade Runner - Director’s Cut. Warner Home Video.1999. DVD.

Shakespeare, William. Love’s Labour’s Lost. 1597.

The Boy with the Green Hair. Dir. Joseph Losey. 1948.

The Damned. Dir. Joseph Losey. 1963.

Thomson, David. ‘Joseph Losey’s rebirth in Britain.’ The Guardian, 21 Jun. 2009. Web. 17 July, 2014.

Email: luminary@lancaster.ac.uk