What drones are capable of in our hands? This is the question raised by Bradley Garrett and Adam Fish in a guest blog post about drone methodologies.

Lost in the concern that the drone is an authoritarian instrument is the possibility that it might simultaneously be a democratizing tool, enlarging not just the capacities of the state but also the reach of the individual. – Benjamin Wallace-Wells, 2014

As we enter the holiday period in much of the world, many of us are receiving requests to give drones as gifts (or asking for them!). More than 1 million drones were sold in 2015, and economists predict the global market expected to reach $1bn by 2018, making it clear that drones are now indelibly a component of our atmosphere. Having drones be part of our lives shapes geographic imaginations, prompting us to reconsider not just how we do things but also how we imagine we might do things. Yet much research in the social sciences has focused on what drones are capable in the hands of the other; less has considered what drones are capable of in our hands. As many of us grapple with whether or not to purchase drones because of issues around price, regulation, and surveillance, perhaps it is time to reframe the debate and to begin asking more phenomenologically-informed questions. If in flying, the human operator is surrounded by the machine, is intimate with the machine, becomes the machine, is overcome by, or reins in the machine, then drone methodologies are already changing how we think and act.

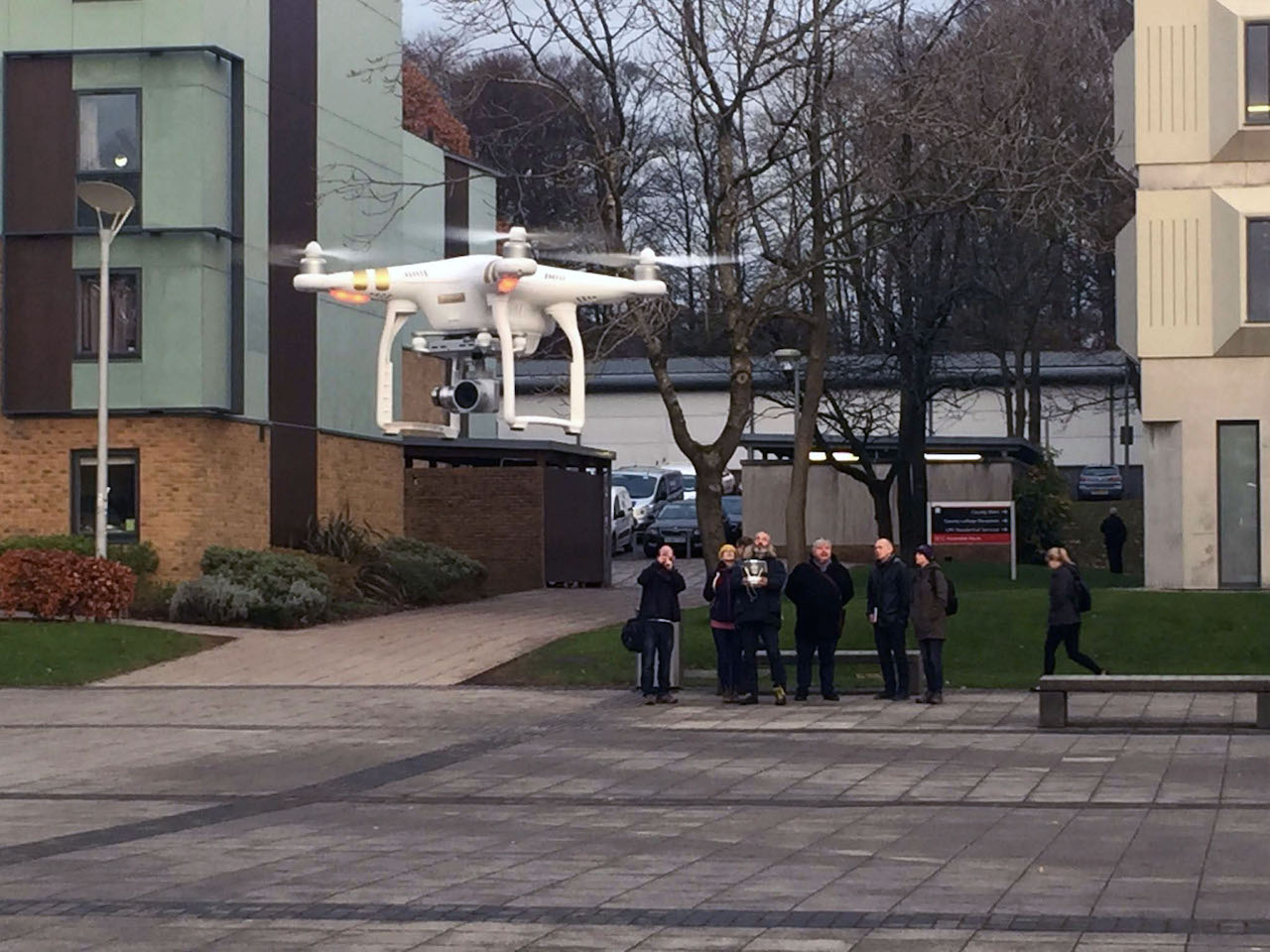

Last month we held a workshop on Drone Methodologies organized through the Lancaster University Centre for Mobilities Research (CeMoRe) as part of a Bradley Garrett’s 2016 visiting fellowship. The workshop was attended by about 20 participants from a wide range of disciplines and included a theortical provocations from Professor Pete Adey (Royal Holloway, University of London). Introducing a range of drones (bare-bones to videographic to racers) linked to a range of flight interfaces (line-of-sight to sutured-iPad to First-Person-View (FPV), we suggested that the drones are increasingly multiple in the ways they fly and sense. This follows Adey’s work in his 2010 book Aerial Life, where he suggests that the aerial gaze is many; it is multiplied and situated in different contexts. It is also a vision that is practised and touched. It is not simply ocular or visual, but an assembly of practices and materials.

In the workshop, the discussions hovered around drones as bodies and about whether they extended the capacities of other bodies or could be considered bodies in their own right (finally earning the badge of autonomy). We also had great contributions from people in regards to the legal and ethical challenges drones present and the potential subversive uses of the technology. Where the conversation really got going, however, was in our interdisciplinary discussions of the speculative future of drones, including military, civilian and research applications. Drone swarms and micro-drones were particular points of contention.

Over the past year, Bradley Garrett has been working with Dr Karen Anderson (Exeter University) to sketch out how the experiences physical geographers have had using drones fit into emerging vertical and volumetric concerns in human geography. Where, as Pete Adey writes, human geography suddenly seems afloat with airs and winds, fogs and aerial fluids, with volumes, verticals and objects in the air, many researchers in the ‘hard’ sciences deploy drones uncritically. Anderson and Garrett have suggested that given their rapidly-advancing sense and avoid arrays and potential payloads, drones have a role to play in linking surface and subsurface and suprasurface spaces. Drones, regardless of their degree of autonomy, are always part of a volumetric assemblage intersecting and mutually constructing those domains. Where Adey asks whether there are other ways of thinking about volumes that appear more open, more plural imaginaries that might not only describe but offer alternative volumes to inhabit, we argue that drones can and should be part of that conversation.

For now, we made clear that this conversation is happening largely without public involvement. A sneaky corporate takeover of the atmosphere is taking place behind closed doors, particularly in the UK —ground-zero for the deregulation of drones for the delivery of packages. As we discussed in our recent Guardian article, Amazon’s Prime Air drone delivery program has been given the greenlight by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). While we are not opposed to the use of drones in this manner — or most other entrepreneurial, funky, or speculative manners — we are concerned that key stratigraphies of our airspace are being diced-up to the highest bidder. In some situations, the ‘highest’ not only means the richest but also the most elevated. As we reported, the Spire, a new £800 million skyscraper in London, is also petitioning to be able to use drones to deliver goods to its penthouse residents. Doing so would be a violation of at least two CAA regulations (pilots must fly with direct line-of-sight and drones may not be flown in ‘congested’ areas). Allowing exemptions from these regulations for corporations reinforces feelings of popular frustration and makes clear, yet again, how public resources (in this case, the very air we breathe) are doled-out to the elite, as we wrote:

Just as skyscrapers have become a visible marker of social inequality in the UK, the ability to fly will also be granted according to privilege, further solidifying the relationship between height and power in the capital.

Towards resisting this, we proposed in the workshop, along with climate change activists and others fighting against privatization of public resources, the concept of an ‘atmospheric commons’. Establishing an atmospheric commons enshrines our rights to the collective air — clean and accessible to the multitudes — and ensured it is not only the domain of transnational corporations who have established cozy relationships with regulators. A commons is defined by the breadth of shared activities the space fosters, so we think it important to fly drones, kites, balloons, etc. and assert our rights (as social scientists, artists, journalists, or people on a lark) to the atmospheric commons. If we don’t do this the atmospheric commons will descend into the typically tragic trajectory.

So that is one of the reasons why we fly. In the summer of 2016, we began a CeMoRe-funded research project using drones totrace and interrogate some of the infrastructure of the internet. This research in still underway but the footage emerging is aesthetically and experientially evocative. While we are still exploring what the drone affords us as a methodology, this workshop provided us with vital time and space to think through the politics of piloting and will inevitably open out many more paths for critical engagement in the future.

We would like to thank Professor Pete Adey for spending nine hours on trains to fly and ruminate on the experiencing of flying with us, Pennie Drinkall from CeMoRe for facilitating the workshop and helping Brad make the most of the fellowship and Paul Scholefield for fixing our racing drone FPV goggles!

Bradley Garrett is an American-born social and cultural geographer at the University of Southampton. He blogs at bradleygarrett.com. Adam Fish is Senior Lecturer in sociology at Lancaster University.