Issue 3: Sleep(less) Beds

Between the Sheets: ‘Lamination’ and Sophie Calle’s The Sleepers

Erkan Ali

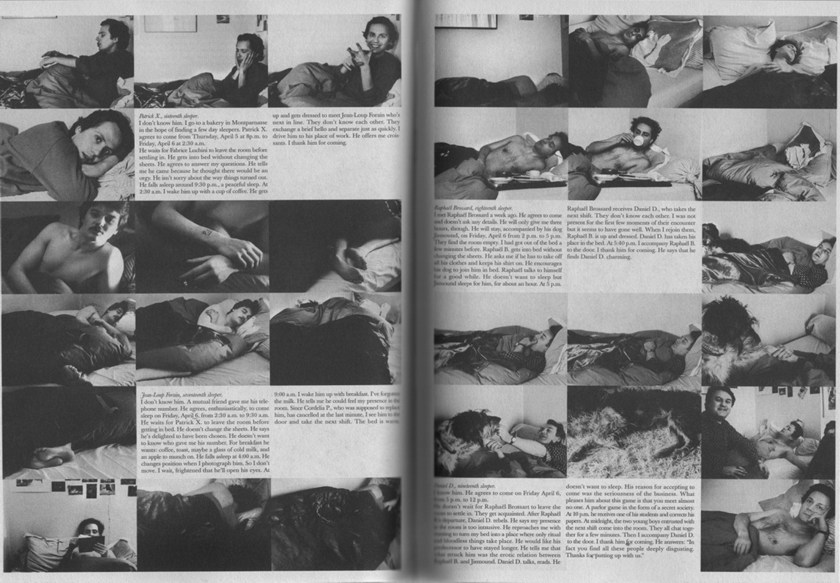

Figure 1

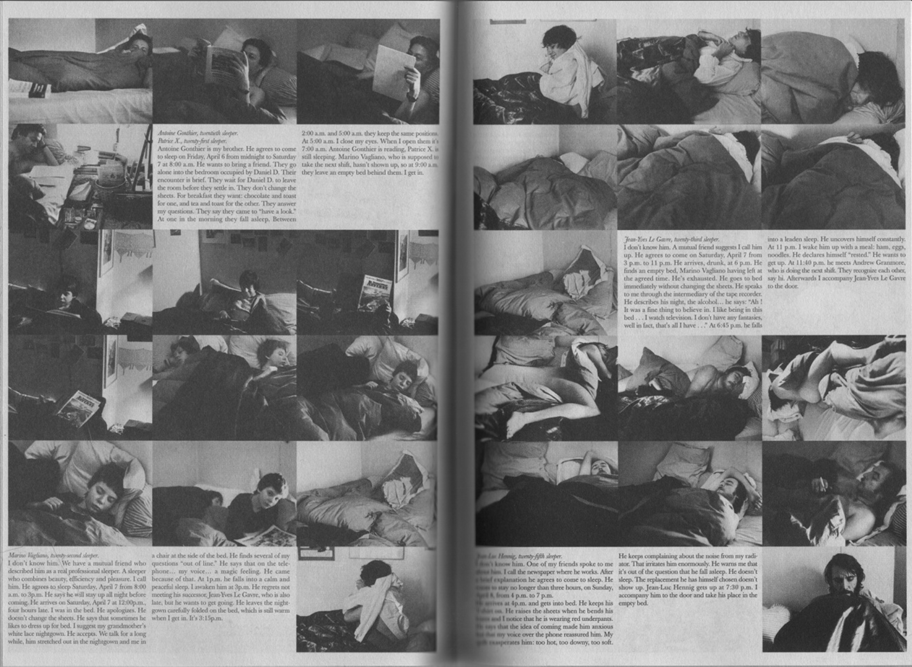

Figure 2

[Image sequences reproduced by kind permission of Xavier Barral and Sophie Calle]

Sophie Calle has built a unique career as a conceptual artist using a combination of texts and photographs in a range of projects. This mode of expression via texts and photographs is undoubtedly the most obvious and telling feature of Calle’s oeuvre; and it is well known that the collaborations between these two media forms are crucial in conveying the meanings of her projects to the reader or viewer.1 In what follows, I will also address this crucial facet of Calle’s work. However, in an attempt at some kind of theoretical originality, I will not discuss it simply in the context of art or aesthetics. Rather, focusing on the sociological relevance of Calle’s use of texts and photographs, I shall invoke them in the context of a concept that I call ‘lamination’.

Calle’s work is ideal subject matter for a discussion and analysis of what I mean by lamination because lamination is a metaphor of construction involving the fusion and collaboration of textual and photographic data in the production of works, which lend themselves to sociological analysis on account of their anthropological or ethnographic relevance. I argue that lamination produces various meanings, which are dependent on the specificity of the texts and images at hand, and which relate to such themes as materiality, narrative, association and memory.2 Specifically, I will discuss how each of these themes is refracted through Calle’s 1979 work The Sleepers, her first artistic project,3 in which she invited twenty-eight people to sleep in her bed in continuous eight-hour ‘shifts’ over nine days (between April 1st and April 9th of 1979).4 In so doing, I will refer not only to the sociological relevance of issues concerning perceptions of public and private spaces, but also spaces that exist between texts and photographs as media forms; how these are exploited for effect by Calle; how these spaces are overcome (or not); and what this means from a semiological and sociological point of view. That is, I shall read The Sleepers as an example of lamination.

The Sleepers and the Blurring of Boundaries

Sophie Calle is well known for her unique brand of ‘socially engaged’ projects,5 regularly involving strangers and members of the public, often unwittingly, in her work. Her oeuvre, as a whole, can be understood as a series of games in and through which she conducts bizarre and interesting social experiments, all of which involve a dialogue between texts and images (of various kinds, but especially photographic images), and all of which involve Calle herself as a main character. In all of her projects Calle plays with social and spatial boundaries; and the role played by the texts and the photographs contributes to this effect.

In the case of The Sleepers, as we shall see, the boundaries are numerous; and they are made blurry purely by the strangeness of the concept that lies behind the project. Calle introduces the project with a textual introduction (she always provides an enticing little synopsis in this way): ‘I asked people to give me a few hours of their sleep. To come sleep in my bed. To let themselves be looked at and photographed…’ (1996, p. 21). On numerous levels, the crucial blurry boundary to be identified is therefore between the public and the private. Calle’s own bed(room) was the physical setting for the game itself; and its photographic and textual representation in/as an art exhibit and a book renders it a public spectacle. However, the state of sleep is perhaps our most intimate and private of inner, personal spaces. Despite her efforts, neither Calle nor her readers can gain access to this from the sleepers’ point of view. Then there is also the peculiarity and awkwardness implied in Calle’s request itself. From the point of view of the participants, it should be said that sleep can be difficult in the presence of others; and the state of sleep or unconsciousness can also render us more vulnerable to physical attack or infringement, although we are not necessarily completely de-sensitised to the external world when we are asleep.6 Taken as a whole, these factors clearly indicate that issues of trust were essential to the success of this project,7 and particularly in the case of those who participated as strangers.8 Characteristic of Calle’s other works, what we find in The Sleepers are issues of accessibility and inaccessibility, as well as visibility and invisibility. It is this set of features that begins to make The Sleepers interesting from a sociological point of view.

The main point behind Calle’s project, as she explains, was to monitor and record her bedroom as ‘a constantly occupied space for eight days’ (Calle, 1996, p. 21). However, as Guralnik notes, often in Calle’s works there is also an ‘attempt to represent what is absent’.9 And this is a crucial observation because, for me, it captures the essence of something else that Calle attempted to achieve with The Sleepers – namely an (a)social experiment. Again, I return to Calle’s opening line from the project because it sums up Guralnik’s point so neatly and efficiently: ‘I asked people to give me a few hours of their sleep’ (1996, p. 21, emphasis added). To be clear, when we ask for another person’s time, we are making a request which, to a greater or lesser extent, acknowledges time as perhaps the most precious of all commodities; and asking for another’s time usually also hints at the shared nature of a particular social exchange, whether formal or informal, with mutual benefits . But cleverly, Calle’s use of the word ‘sleep’ – as opposed to ‘time’ – indicates the largely one-sided nature of the (a)social situation in her experiment. Essentially, it is therefore an absence of sociality that is represented in The Sleepers, via the blankness of sleep and the one-way direction in which it is represented. Aside from her own occasional shift in the bed, the passage of time really only exists as a conscious experience for Calle; her subjects, oblivious to the world if they do sleep, do not experience the events consciously. Socially speaking, theirs is a kind of dead time.

This is what Calle was seeking with this project: access to the non-social side of people’s lives, without compromising the intimacy (the mutuality of physical presences) which is imperative if the motif of social suspension is to be applicable (because, after all, cameras do not necessarily need a constant human presence in order to function). The state of sleep is perhaps the only one that can permit this unique relationship of absence and presence in the same moment. Indeed, social interaction with each participant was of course necessary in the initiation of this game; but just like the minds and the bodies of Calle’s subjects, in Calle’s game social structures and interactions go to sleep for a given period of time, allowing her exclusive access to her subjects from a position that they themselves can never really experience. Interestingly, the unilateral nature of Calle’s experience here is, to some extent, mirrored in the practice of photography itself. According to Sontag, ‘[t]o photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed’.10

Calle regularly plays with the dynamics of visibility and the different subject positions involved in these. For instance, voyeurism is often mentioned as a crucial theme in Calle’s projects.11 However, Calle’s game in The Sleepers implies a quite different relationship between the observer and the observed, namely one of surveillance. To be part of this little game is an act of faith; it is to trust implicitly and to hand complete control of the situation over to Calle. Simply to allow oneself to be watched in this way is an expression of trust. Calle therefore imposes, crosses and blurs social and personal boundaries in this project; as she monitors and records her subjects, Calle’s position as watcher is a privileged one, which is reminiscent of the ‘panoptic gaze’ described by Foucault in Discipline and Punish. In Foucault’s words, Calle’s are the ‘eyes that must see without being seen.’12 And the presence and use of the camera is directly relevant to this also because, firstly, photographs have an assumed evidentiary power; secondly because the camera is a device that records realistic images that would (visually) give away the identities of Calle’s participants;13 and lastly because the photographer is free to make selections. This final point seems particularly relevant. As Sontag (1979: 4) puts it, ‘[t]o photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge – and, therefore, like power’. Indeed, it has been said that, typically in her projects, Calle ‘chooses to become involved in a random situation, but from the moment of entry she controls the situation with obsessive manipulation and reports about it in a systematic, calculated manner and in a cool, aloof style.’ (Guralnik, p. 216). The Sleepers epitomises this description of Calle’s method.

Controversy

In playing with boundaries in such ways, Calle has sometimes courted controversy with her projects. Perhaps the most famous example is The Address Book (2003 [1983]), in which Calle tells of how, one summer’s day, she found an address book on the ‘rue des Martyrs’ in Paris.14 Despite noticing that, sensibly, the owner (‘Pierre D.’) had written ‘his name, last name, address and phone number’ on the ‘first page’ (Calle, 1996, p. 110), Calle elected not to contact him directly, but to photocopy the book before sending it back to him and then proceeding to work her way gradually towards an understanding of him by contacting his friends and acquaintances and building-up a composite picture of him based on their descriptions of his physical and personal characteristics. The technical term for this use of texts in building a kind of image (or the use of one artistic medium to produce another) is ‘ekphrasis’,15 and it is another example of how Calle plays with text, image and imagination in the conceptualisation and materialisation of her work. Calle arranged meetings with many of the individuals listed in the book, only revealing the name of its owner during the meetings themselves.

Eventually, over the course of a month, she serialised ‘an alternative portrait’ of Pierre in the French newspaper Libération along with photographs of the informants, or of the places where the meetings took place.16 Discovering this on his return from a trip after filming wildlife in Norway, Pierre was furious. He published a nude photograph of Calle and threatened to sue her if she continued to invade his privacy by ‘reproducing the Libération pieces in book form’ ( Saint, p. 126). The Address Book epitomises the mischievous nature of Calle’s work as she regularly flirts with controversy, pushing or obscuring the boundaries of social (and sometimes legal) acceptability . Texts and photographs are always fully integrated into this. As media forms, texts and photographs are powerful records and testimonies; in a word, both have evidentiary value or potential, and they are used by Calle as central components in order to exploit the situation at hand. Despite the measure of anonymity initially afforded to him, Pierre D.’s objections were clearly based on the power and potential of photographs and texts to represent and misrepresent events and individuals, especially in a public context such as that of a national newspaper. Regardless of the accuracy or inaccuracy of her alternative portrait of him, Pierre regarded Calle’s prying into his life as an invasion of his privacy. This is how Calle’s use of texts and images can be said to sometimes raise ethical questions.

Standard Commentaries

To paraphrase Walter Benjamin on the art of critique, in order to know what one can write in relation to ‘a subject’ of interest one has to know what has already been written because such knowledge is not only a way of ‘informing oneself’, but also, more practically, of enabling the possibility of making an original contribution to the particular set of discourses at hand.17 This is a guiding principle for my discussion of Calle’s work, with which a number of themes are often associated.

Firstly, Calle’s work often blurs the boundaries between the public and the private. For example, according to Vest Hansen, ‘Calle operates as a catalyst for ‘ordinary people’s’ autobiographical stories to represent and question public places and private spaces’. Secondly, it is often pointed out that Calle blurs the distinction between art and documentary. Garnett notes that, although Calle ‘doesn’t paint or draw or sculpt, and she doesn’t exactly make things or make things up’, her ‘images tend to be documentary style photographs, and the text is narrative, explanatory and personal, even when it is about someone else’. Lastly, it is also well known that in Calle’s life and work, fact and fiction have become intertwined.As a result of their romantic involvement, for instance, Calle collaborated with the writer Paul Auster on numerous projects and she was the inspiration for a character, ‘Maria’, that Auster developed in his novel Leviathan (1992).18 ‘After reading the novel,' Duguid notes, ‘Calle decided to try and become the character, to recreate the parts of Maria that Auster had made up.’19

As we have seen, and as we shall see further, reflections on the use of texts and photographs form part of these standard commentaries on Calle. Using these media forms, Calle’s works are essentially investigations into the social world and the reality of the lives that comprise it; this gives her work a sociological dimension, taking it beyond the realms of art. I am also addressing this range of themes associated with Calle’s work, but I am doing so in the context of lamination.

Texts and Photographs: Lamination

The title of my PhD thesis is Lamination: re-thinking collaborations of photographs and texts.The concept of ‘lamination ’ is inspired by an observation by the French cultural critic Roland Barthes on the construction of the paper photograph as a ‘laminated object whose two leaves cannot be separated without destroying them both.’20 Barthes’ main concern in making this observation, though, is not the photograph itself but the referent or image inside it – this is the photograph’s essence, its meaning , because in Camera Lucida Barthes is concerned not with semiotic interpretations of photographs via textual explanations and interceptions, but with the significance of the sheer presences within them. According to Rancière, Camera Lucida therefore represents a radical break from Barthes’ earlier preoccupation with a cautious, semiological critique of photographic images as ‘mythological’ objects.21 That is, in this case, as objects whose meanings are culturally-specific, but whose communicable potential (via the realism of their image) allows them to be paraded as self-explanatory documents. In abandoning this strict critical approach to photographic images, Barthes is embracing the idea that the referent in a photograph is a direct link to the past, a visual trace of a subject or object ‘that has been’ (Barthes, p. 80). For Barthes, the photograph, unlike text or language, is a medium that is capable of carrying its referent within itself. In Barthes’ later writings on photography, the referent therefore becomes the essence of the photograph’s communicability as conventional language becomes redundant. This represents a complete about-turn in Barthes’ reflections on photography.

In Camera Lucida, then, Barthes is making an ontological claim: if we damage the photograph we damage the image and its realism, and we thereby destroy the photograph’s essence or meaning. On another level of abstraction, I am arguing that texts and photographs can also ‘laminate’ each other. They become fused; they collaborate to produce a single piece of work or artefact; they are mutually supporting; they become associated with each other; and, as with construction of the paper photograph, they can also trap meanings between them (like insects in amber). These are the basic premises of lamination as I am defining it. It is intended as a sociological concept for understanding and analysing the constructions, associations and meanings produced by photo-text amalgams. With lamination I am reinstating the significance of text in order to reconceptualise the effects that it can have on the use of photographic images in various contexts. Put simply, I am therefore using Barthes’ supposedly post-semiotic perspective on photography to re-establish a semiotic relationship between photographs and texts because, as a metaphor of construction, lamination works as an overall system or meta-narrative for understanding associations between the two media and the effects that such associations are capable of producing.

To be clear, I identify a number of processes or stages involved in lamination. These are: exemplary lamination, substantive lamination, de-lamination, re-lamination, mis-lamination, ironic lamination and meta-lamination. Lamination refers to any construction in which text(s) and photograph(s) are combined; exemplary lamination refers to efficient and precise uses of texts and photos, usually involving one photograph and a caption; substantive lamination refers to extended and multi-layered combinations in which meanings, as they build, become more complex and manifold; de-lamination refers to the destruction of meaning that occurs when photos and texts are separated, torn from one another for the use of either in a new context; re-lamination refers to the reintroduction of texts and photographs in new configurations and contexts; mis-lamination refers to the gaps that can exist between texts and images and to those situations where textual descriptions and visual appearances are incompatible; ironic lamination refers to the versatility of both writing and photographs as media forms with multiple meanings and their use in combination to exploit this versatility. Finally, meta-lamination describes a kind of master lamination, an over-arching text or narrative, which is used to compress and make transparent a number of perspectives under a single perspective. This paper is therefore a meta-lamination of Calle’s work.

‘The Sleepers’ as a Lamination

In published versions of The Sleepers, the photo-text sequences usually consist of brief and efficient written descriptions followed by a number of photographs depicting the participants in Calle’s game at various stages during their shifts – sometimes apparently in deep sleep, sometimes wide awake and bored, while at other times apparently addressing the camera directly and interacting with Calle (see figures 1 and 2 above ). Importantly, as Macel points out, Calle regularly ‘adopts the style of the “report” – complete with facts, precise times, and so on – to be written up’. (p. 21) In The Sleepers, examples of this are plentiful as Calle gives details relating to the activities of the participants: ‘They fall asleep at 1 a.m.’ (1996, p. 39);22 and also to her own activities as she directs proceedings: ‘I photograph her often during the night. She changes position but doesn’t open her eyes. At 9 I awaken her while taking a picture’ (1996, p. 32).23 This matter-of-fact style hints at the importance of surveillance in Calle’s work; it relates to the sense of control that she typically wants to have over her subjects. Despite the absurdity of the circumstances, it is not the remarkable or the spectacular that is being monitored here, but the ordinary. Each report begins with the sleeper’s number in the sequence; and we are almost always given an indication as to Calle’s familiarity with the individual(s) depicted: ‘I know her’; ‘I don’t know him’; ‘he’s my brother’; ‘she’s my mother’.

Although the text does not correspond directly with specific photographs to offer a blow-by-blow account of each moment, it is still true to say that without the text, the photographs would make very little sense . This is why I invoke lamination and the effects (or meanings) it is capable of producing. The essential and initial effect is association as photos and texts are brought into relations of juxtaposition, creating a productive tension. Another effect of lamination is narrative, which, in successful cases, builds gradually as the texts and the photographs enter into dialogue with each other. Accordingly, in The Sleepers, we have a situation in which both media collaborate with each other, lending to and borrowing from one another, offering their unique effects and compensating for the limitations of each. The text establishes and explains the game, and helps to carry the narrative forward; for their part, the photographs give the reader a visual insight into the events. The result is a sequential narrative, a substantive lamination. A final effect of lamination is memory; a record is a kind of memory, often a physical kind, which attests – or claims to attest – to the actuality of some or other event. Despite this, importantly, it should be noted that ‘truth’ is not necessarily an effect of lamination. Lamination is mainly concerned with meaning-making, how it is produced, how it is built, conveyed, altered, interpreted, and preserved; it is not concerned with ‘the truth’ of things per se. And yet, the use of photographs in Calle’s work acts as a particularly powerful and persuasive form of ‘evidence’, corroborating the report-like script. This is a process about which I shall say more below.

Given Calle’s aim to maintain her bedroom as an occupied space over a given period of time, she had each of her guests formally ‘receive’ the succeeding guests at the change of each shift. This is recorded photographically as we see new and old guests greeting each other by shaking hands and often conversing. For its part, the text announces the arrival and the departure of the guests in each case. Analysing the sequences, we find ourselves oscillating between the texts and photographs in order to keep track of who the sleeper is, what their number is in the sequence, whether they fell asleep or not, what time they fell asleep and for how long, how they behaved while asleep or awake, and so on. With her textual reports, Calle provides details on all of these points.

The textual descriptions and photographic evidence therefore become part of a continuous chain of representation (orderly and from left to right and top-down, just like the structure of written forms of Western language systems ), thereby mimicking and mirroring the connected temporal chain of events between April 1st and April 9th of 1979. This is a crucial effect of Calle’s lamination. The images are dependent on the text to produce the order. How the two are arranged is an important part of the construction; it is not simply the content of the text and photos that matters. What we find in The Sleepers, then, is an example of what I call ‘substantive lamination’. In substantive lamination, what we have is a complex layering of information as multiple photographs and texts combine to produce a narrative or a sequence. Indeed, it has been said of other exhibitions by Calle that they ‘call for a linear reading.’24 Order and sequence are always part of the presentation. The act of recording that is a crucial aspect for Calle. The little details and occurrences are important in as much as, in photographic and textual form, they refer to events that took place between the dates and times that are specified. According to Bois, ‘Calle’s work is not concerning remembrance but contingency.’25 Yet there is an aspect of memory involved in this contingency, in this relationship between text and photograph. In The Sleepers, the photographic evidence and the textual data are records; and the associations between them have the effect of holding those eight days of history firmly in place, to testify that Calle’s bedroom was indeed occupied during the whole of that time.

This is how Calle’s The Sleepers is laminated. The narrative builds as the textual intervention at the start of each new visual sequence acts like the passing of a baton in a relay race, as the succeeding sleepers meet the preceding ones; and we are given the precise dates and times for each shift and each change of shift. But the content of the text is also important, as Calle uses it, often comically, in order to divulge little pieces of information about the participants in the game, perhaps giving us clues as to their individual psychologies and expectations; and we are able to infer connections between the photographs and the texts based on these descriptions of events. For example, Calle explains that when she asked Frabrice Luchini, the fifteenth sleeper, ‘what he thinks he’s doing in my bed he answers: “Sex”’ (Calle, 2003, p. 149). Accordingly, there are numerous images of Fabrice lying on his side and gazing into the camera, apparently suggestively. Fabrice’s immediate successor, ‘Patrick X.’, the sixteenth sleeper, tells Calle that ‘he came because he thought there would be an orgy’, though he also reveals that he ‘isn’t sorry about the way things turned out’ (Calle, 2003, p. 150). Such issues as gender and sexuality therefore also become important and interesting themes in Calle’s project, even if they were not part of her original agenda or design.

In addition to the intimacy of the situation, the centrality of the bed as a theme in this project perhaps makes it almost inevitable that sex is invoked as a corollary. Discussing his first encounter with Calle’s work by way of an exhibition of The Sleepers ‘at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris’, Mordechai Omer notes that his immediate ‘associations led’ him ‘to artists like Picasso and Magritte, who also dealt with sleeping people, with sleep itself and with the way people who are awake react to it.’26 The link made with Magritte emphasises his juxtaposition of (divergent) images and words in the series of paintings he called La Clef des Songes (The Key of Dreams)27 Omer notes that, often in the examples of Picasso’s art, the gaze is male, and it is directed towards a female who is sleeping. Again, issues of (heterosexual) male power and visibility are invoked here. The female body, incapacitated and exposed, is at the mercy of the male gaze. Magritte, of course, belonged to the Surrealist movement; and in Surrealist art, sex and eroticism were almost always present themes, albeit usually in more subliminal forms. In The Sleepers it is a woman’s gaze that is in control, often presiding over a male sleeper. In The Sleepers we therefore find elements of Calle’s customary playfulness and mischievousness, in this case as she turns the tables to distort classic gendered themes in artistic representations. Indeed, a strong feminist agenda has been cited as an important theme in Calle’s work. (Chadwick, p. 111)

This blurring and crossing of boundaries are general themes which therefore extend to the act and the means of representation, and not just to the specificity of the game itself. These are important points from the perspective of lamination. Calle uses texts and photographs in her unique brand of conceptual art in order to emphasise the characteristics of each medium, usually as evidentiary materials and narrative tools at the same time. In Calle’s works, the factual and the fictional merge and fuse, just like the text and the photographs. Macel defines Calle’s work as a series of ‘innovative criss-crossings of factual narratives with fictional overtones, accompanied by photographic images’. (p. 21)

Both writing and photography can hold claims to truth, just as they can both deceive. But a crucial point about the concept of lamination is to emphasise not that texts are necessarily more reliable or truthful than photographs or vice-versa, but that, as media forms, they function differently. Indeed, it is precisely these very differences that encourage their strategic juxtapositions. Discussing Calle’s deployment of each medium, Macel captures the sentiment: ‘In most instances, text is associated with image, in a kind of dialectic about issues to do with the visible and the expressible (in words) – the sayable, otherwise put’. (p. 21) Therefore, Macel adds, ‘Sophie Calle works in the interstitial gap between photography and the imaginativeness of writing, where the imaginary triumphs.’ (p. 22) Again, this dialectics is precisely relevant to lamination. Lamination is a sort of dialectics , a quiet sort that is only noticeable when it is exposed by the critic or analyst. This relates to the earlier comments concerning the productive tension that exists between texts and photographs as distinct yet compatible media forms. The text and the photographs tend to borrow from each other; they each have certain strengths and weaknesses, but they nip and tuck to produce a narrative; and the narrative that is produced benefits from the influence of each. Calle recognises the importance of both. She writes: ‘In my work, it is the text that has counted most. And yet the image was the start of everything’ (Calle, 2011). Calle’s first forays into art, through her photography, have set in train not only a unique and remarkable style but a whole set of discourses as well. In relaying this interpretation of The Sleepers, this ‘meta-lamination’, I am helping to convey its message at the same time as I am adding new layers to it. I am thereby discussing The Sleepers as a lamination at the same time as I am incorporating it into a new lamination. This goes some way towards explaining the dialectical function of lamination as a continuous process.

Calle’s work is so rich, varied and smart, that it has been referred to not just in the context of writing or art or photography,28 but in a number of other ways too: in the context of ‘ethnography,’29 or a ‘sociology’ of sorts (Bois, p. 31), and even acting or ‘performance’ art (Calle, 2011). However, the suggestion that Calle is a kind of sociologist is particularly intriguing. As Garnett points out, Calle has an ‘obsession with the sheer strangeness of life’. This is true, but it needs to be made clear that her obsession is with what is local, with that which is right under our noses, but goes generally unnoticed (like the purloined letter in Poe’s short story); her observations are often intended to point out that life itself – encompassing our social rules and customs – is the very thing that is peculiar; the social world is, by definition, strange, especially when it is most familiar. Putting the absence of theory to one side, this is where Calle shares an affinity with the sociologist because, to invoke Mills, the art of good sociology demands a particularly fertile, inquisitive and perceptive ‘imagination’ for the extraction of the remarkable and the wonderful from the ordinariness of the everyday world that surrounds us.30 And like a visual ethnographer, Calle records and conveys her observations through photographic evidence and a written account. The title of one of Calle’s published collections, True Stories (1996), is apparently a clever pun that, as we have seen, captures an important sentiment relating to her style of lamination, which is that stories can contain truth and that there is no reason why truth itself cannot take the form of a narrative; in fact, it routinely does. In Calle’s many projects, the ‘truth’ of the photographic image confirms the truth of the stories that might otherwise be made-up, as stories often are.

Traditionally, sociology has tended to be ambivalent about the ‘truth’ of still images in data.31 While this still remains the case, in more recent decades, interest in photography has been rejuvenated in visual sociology and ethnography.32 The photograph therefore remains an enduring object of sociological critique while becoming an increasingly legitimate source of information for the sociologist. For these reasons, the sociologist takes a certain cautious approach to the use of photographs; and a textual accompaniment to the image is almost always present for the purposes of clarity and explanation. Nevertheless, as with visual sociology, Calle’s use of photography and text together is intended to strengthen her observations. The claim and impact of her work is not sociological but artistic. And yet she addresses many of the issues that we find in sociology: the everyday, routine, bodily, material life – everyone sleeps almost every day. There is also the division between the public and the private, which is a common theme in sociology. The games that Calle creates regularly toy with this set of themes and via the concept of lamination I have tried to show that her deployment of texts and photographs is also part and parcel of a style that makes her work relevant to sociological analysis and interpretation. However we wish to define them, then, her projects are, in the end, laminations.

Conclusion

Barthes’ observation on the construction of the paper photograph as a laminated object whose construction and maintenance is vital to the meaning it holds is central to the metaphor of lamination, which I have discussed as a conceptual tool for the extraction of sociologically-relevant information from works which lend themselves to such an analysis. (Barthes, p. 6) I have discussed the works of Sophie Calle – and particularly The Sleepers – as examples of what I mean by lamination. Between the sheets or layers of text(s) and photograph(s), meanings are captured and held. I have tried to demonstrate that this as an effect of lamination, of the association of texts and images in juxtaposition. But the fusion of text and image also allows for the integration of these two different yet compatible media forms in the production of narratives as both text and photograph complement each other to exploit and overcome the spaces and gaps that exist between them.

And in discussing Calle’s The Sleepers in such ways I have also been engaged in lamination in its various guises. I have de-laminated aspects of Calle’s work – textual and photographic – and have re-laminated them here to form this new commentary, a new construction, a meta-lamination. By doing this, my intention has been to build an argument in order to demonstrate the sociological significance of Calle’s work by drawing on the numerous themes that are often invoked in relation to it: the social games she engages in, the ethnographic nature of her work, the blurring of various boundaries, the controversy and, of course, the texts and the photographs. Using examples of both texts and photographs, I have compressed and made transparent each of these themes under this new construction, which is, in itself, an example of lamination.

References / Notes

1 Christine Macel, ‘The Author Issue in the Work of Sophie Calle’ in M’AS-TU VUE? Did you see me? Sophie Calle. (Munich, New York, Paris, London: Prestel, 2003). See also: Sophie Calle, ‘I asked for the moon and I got it’, The Guardian, Sunday 9 January (2011).

2 A versatile metaphor, lamination lends itself to each of these themes in physical, conceptual and visual ways. Laminates are material goods, they have substance: I refer to books and articles as laminates. Laminates are constructions, involving layering (just as narratives are constructions that involve layers and layering). Lastly, the meanings created by (or between) the layers can be stubborn and lasting, especially conceptually, and this point links to association and memory.

3 As Macel points out, The Sleepers was in fact Calle’s second project, coming after Suite Vénitienne, which is wrongly dated as being produced in 1980. Macel writes: ‘in the case of Suite Vénitienne (1980), where she shadowed a certain Henri B. from Paris to Venice, she had no option but to post-date the work as a safeguard against being taken to court by him. The Suite is thus regarded as her second work, when in fact it was her first, predating The Sleepers, produced in 1979, by a few months’ (2003, p. 25).

4 Sophie, Calle [1979], ‘The Sleepers’ in True Stories, Sophie Calle, The Helena Rubenstein Pavilion for Contemporary Art: Tel Aviv Art Museum (1996), pp. 20-49; Sophie, Calle [1983] ‘The Address Book’ in M’AS-TU VUE? Did you see me? (Munich, New York, Paris, London: Prestel, 2003); Sophie Calle [1979], ‘The Sleepers’ in M’AS-TU VUE? Did you see me?

5 Malene Vest Hansen, ‘Public Places-Private Spaces: Conceptualism, Feminism and Public Art: Notes on Sophie Calle’s The Detachment’. KONSTHISTORISK TIDSKRIFT, 1: 4 (2002), p. 199.

6 For example, when we enter a space in which another person is sleeping, the person might sense our presence and will stir or move or perhaps even speak, emphasising the thin line that divides the states of sleep and wakefulness. This kind of effect is hinted at by Freud, on dreaming, in his discussions of ‘external stimuli.’ See: Sigmund Freud [1913], The Interpretation of Dreams, trans. by A.A. Brill. (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1948), p. 217. He also notes that ‘actual sensations experienced during sleep may constitute part of the dream-material.’ (p. 314)

7 The element of trust is emphasised best in the case of ‘the fourteenth sleeper’ in Calle’s game, the girl from the baby-sitting agency, ‘Kid Service’, for whom Calle had paid ‘54.50 francs’ for three hours (Calle, 1996, p. 36). Calle writes: ‘She introduces herself. I ask her to sleep for me. She’s worried. She fears I’m a homosexual and that I’m going to attack her. She decides to stay; nevertheless the idea of going to bed repels her…She says she’s tired but that it’s out of the question that she go to sleep’ (p. 36).

8 Of course, this applies both ways as Calle invited strangers into her home and bedroom. However, allowing oneself to fall asleep in the presence of a stranger is a particularly trusting gesture. Incidentally, some of the participants were friends of Calle’s, or family members; the twentieth sleeper was her brother, and another of the sleepers was Calle’s mother, who in fact became a regular participant in her subsequent art projects.

9 Hehama Guralnik, ‘Sophie Calle: True Stories’ in True Stories, Sophie Calle (The Helena Rubenstein Pavilion for Contemporary Art: Tel Aviv Art Museum, 1996) pp. 209-218 (p. 210)

10 Susan Sontag, On Photography. (London: Penguin Books, 1979), p. 14.

11 See Daisy Garnett, ‘In bed with Sophie Calle: The artist’s parody of Brigitte Bardot in ‘Days lived under the Sign of B, C and W.’’ The Daily Telegraph: Appointment with an artwork, 15 August (2005).

12 Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: the birth of the prison. (London: Penguin Books, 1975), p. 171.

13 Names are also given in the text. Although we can never be certain if these are genuine, there is no suggestion that they are false. Sometimes Calle will provide a first and second name for her participants. But on other occasions – perhaps by request – she is more discreet, referring to a participant by using a first name and an initial for the surname, such as ‘Daniel D.’ or ‘Patrick X.’ (Calle, 2003, pp. 148-149).

14 Whitney Chadwick, ‘Three artists/Three women: Orlan, Annette Messager and Sophie Calle’, Contemporary French Studies and Francophone Studies, 4:1 (2000), 111-118. (p. 113).

15 W. J. T. Mitchell, ‘There Are No Visual Media’, Journal of Visual Culture, 4:2 (2005), 257-266 (p. 263).

16 Nigel Saint, ‘Space and Absence in Sophie Calle’s Suite Vénitienne and Disparations’, L’Esprite Créateur, 51: 1 (2011), 125-138. (p. 126)

17 Walter Benjamin, ‘Notes (III)’ in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Vol. 2 Part I, 1927-1930, trans. by Rodney Livingstone, ed. by Michael Jennings with Marcus Bullock, Howard Eiland and Gary Smith. Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999), p. 285.

18 Nicola Homer, ‘Sophie Calle: Talking to Strangers’, Studio International, 23 November (2009). Available from: http://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/sophie-calle-talking-to-strangers [Accessed 18/05/13].

19 Hannah Duguid, ‘Up close and (too) personal: A Sophie Calle retrospective’, The Independent (Monday, 26 October, 2009). Available from: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/up-close-and-too-personal-retrospective-1809346.html [Accessed: 10/01/2013].

20 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: reflections on photography, trans. by Richard Howard. (New York: Hill and Wang, 2000), p. 6.

21 Jacques Rancière, The Future of the Image, trans. by Gregory Elliot. (London: Verso, 2007), pp. 10-11.

22 This is in reference to the twenty-six and twenty-seventh sleepers (respectively, Roland Topor and Frédérique Charbonneau) who shared the same shift.

23 This is in reference to Jennie Michelet, the thirteenth sleeper.

24 Sophie Berrebi, ‘Sophie Calle’, Frieze Magazine, Issue 44 (1999).

25 Yve-Alain Bois, ‘“The Paper Tigress”’ in M’AS-TU VUE? Did you see me? p. 30.

26 Mordechai Omer, ‘I Sleep, But My Heart Waketh’ in True Stories, pp. 220-222. (p. 222)

27 I would refer to such mutually-repellent image-text juxtapositions as ‘mis-laminations’ because there is a mismatch between the two. Interestingly, Freud (The Interpretation of Dreams, p. 47) discussed how, with or without images, textual characters and words can also appear in dreams as ‘hypnogogic hallucinations’; hypnogogic hallucinations are described as ‘those very vivid and changeable pictures which with many people occur constantly during the period of falling asleep, and which may linger for a while even after the eyes have been opened’.

28 For writing, see Macel (2003); For art, see James Campbell, ‘Sophie Calle’, Border Crossings, 27: 4 (2008).

29 Michael Sheringham, ‘Checking Out: The Investigation of the Everyday in Sophie Calle’s L’Hôtel’, Contemporary French and Francophone Studies, 10:4 (2006), 415-424, (p.420).

30 C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination. (London: The Oxford University Press, 1959)

31 Mike Ball and Smith, Greg, Analyzing Visual Data. (Newbury Park, CA.:Sage, 1992)

32 See: Howard S. Becker, ‘Visual Sociology, Documentary and Photojournalism: it’s (almost) always a matter of context’ in John Prosser (ed.) Image-based Research. (London: Routledge, 1998) and Douglas Harper, Visual Sociology: an introduction. (London: Routledge, 2010).

Email: luminary@lancaster.ac.uk