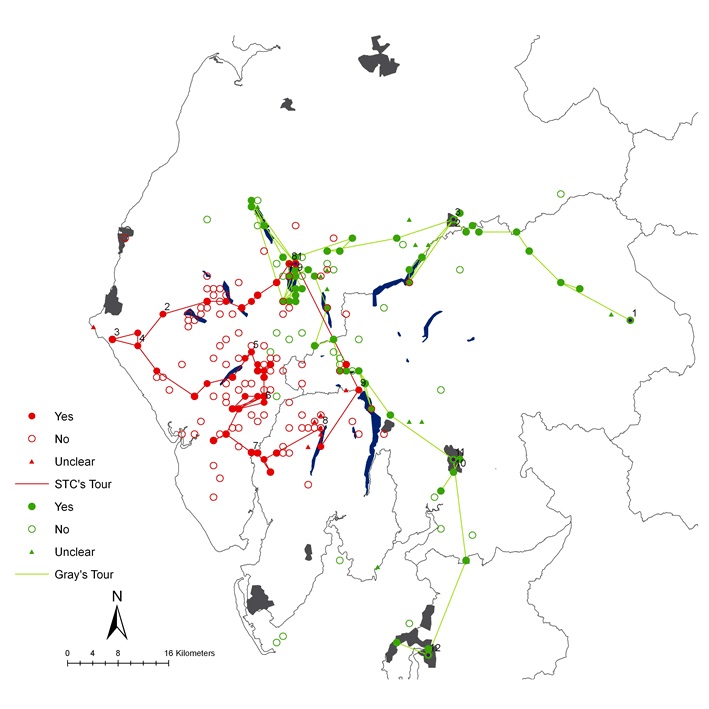

In the ‘Mapping the Lakes’ pilot study, we used straight lines to represent the paths of two famous early Lakeland tours (figure 1). This connect-the-dots strategy does succeed in tracing the sequence of places the two writers visited; however, it tells us next to nothing about what these writers thought and felt about the places through which they passed.

Figure 1. Comparative map displaying the places mentioned in Thomas Gray’s epistolary journal of his Lakeland tour of 1769 and in the notes and letters S. T. Coleridge composed whilst on his ramble through the region’s western fells in 1802.

Figure 1. Comparative map displaying the places mentioned in Thomas Gray’s epistolary journal of his Lakeland tour of 1769 and in the notes and letters S. T. Coleridge composed whilst on his ramble through the region’s western fells in 1802.

As we see it, we need to nuance our analysis of the findings we derive through this kind of quantitative mapping by investigating the different sorts of attributes the texts in our corpus assign to places in the Lake District. Specifically, we’re interested to see if specific places more strongly associated with particular attributes than others, and if the relationship between places and their attributes remains fixed or changes with the passage of time.

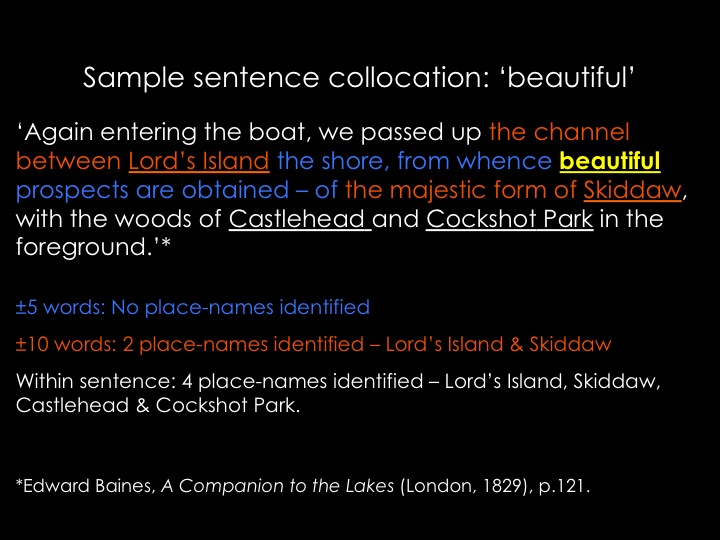

With this in mind, we’ve recently undertaken an experiment using collocation analysis to examine the relationship between the place-names in our corpus and a set of search terms, such as beautiful, delightful and melancholy, all of which relate to particular kinds of emotional and aesthetic experiences.

For simplicity sake, we selected to use sentence boundaries for the collocations in this experiment. Because, despite the occasional errors of inclusion this may introduce, we’ve discovered that in sentences containing multiple place-names the search query is frequently applicable to each of the different locations.

In the example shown below, for instance, ‘beautiful prospects are obtained’ not only of Lord’s Island and Skiddaw, but also of Castlehead and Cockshot Park. So a collocation with each named entity is not just acceptable, it’s desirable.

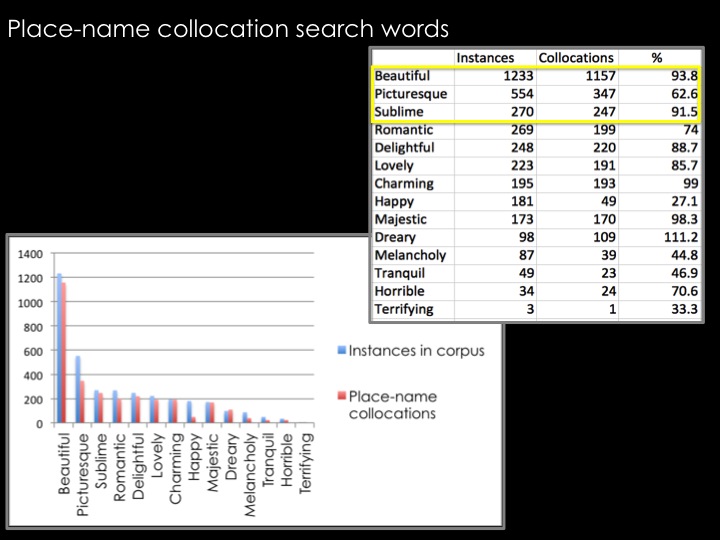

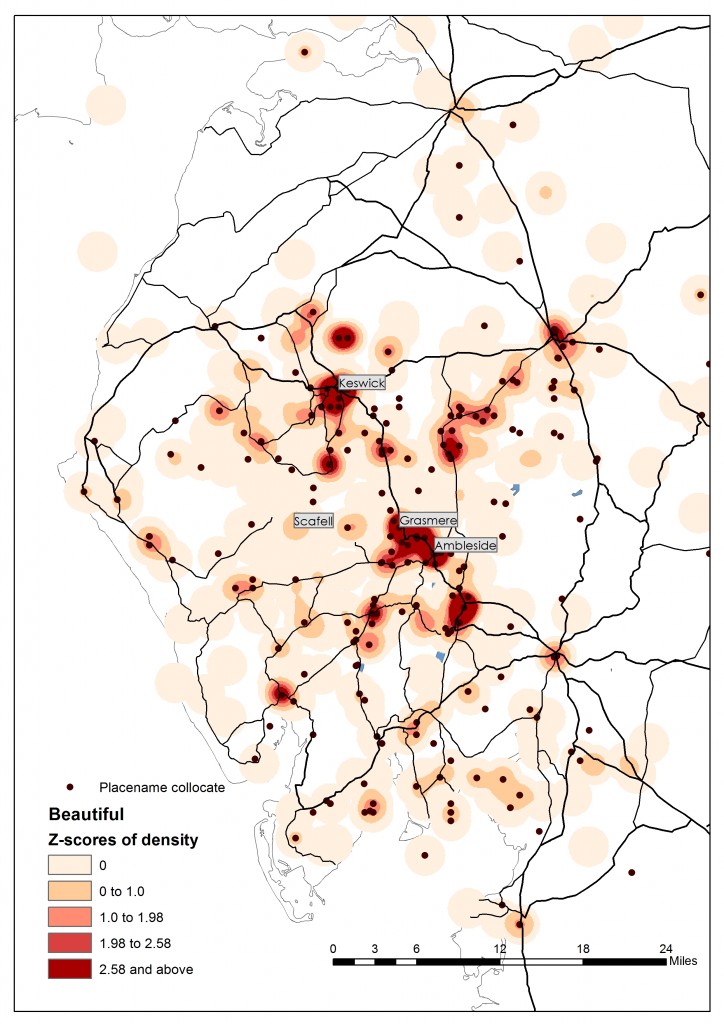

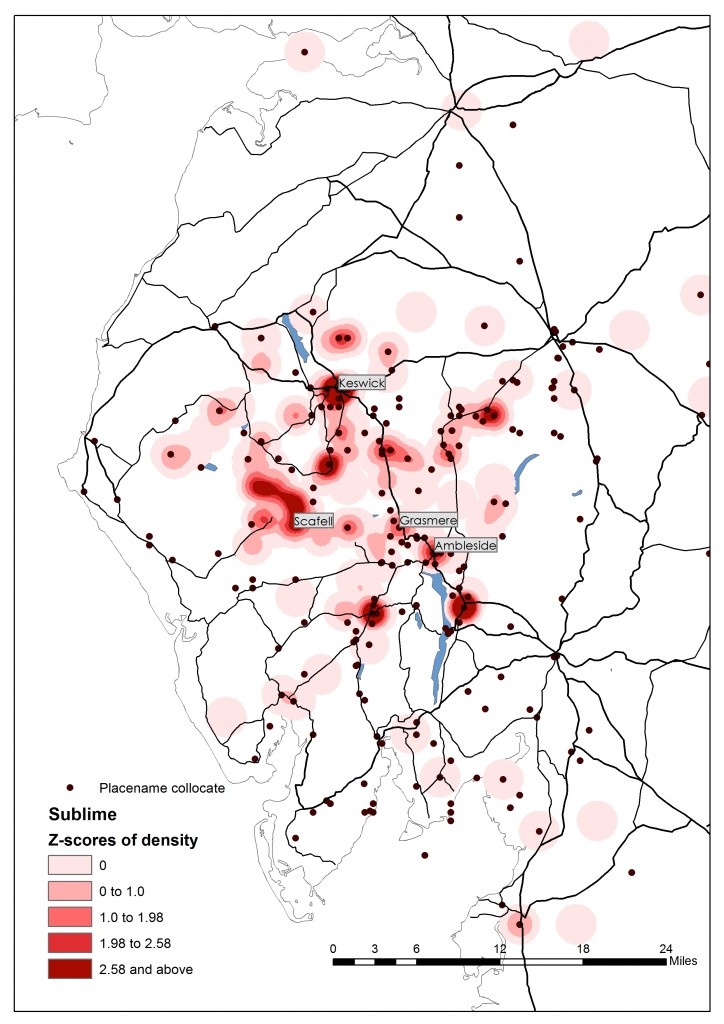

We’re still analysing the outcomes of this experiment, but we were immediately intrigued by the number of the place-name collocations with the word ‘beautiful’, as well as those with the words such as ‘picturesque’ and ‘sublime’. These are three of the most prominent words in our corpus, as they are all integral concepts to the landscape aesthetics which drew tourists to the Lake District during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

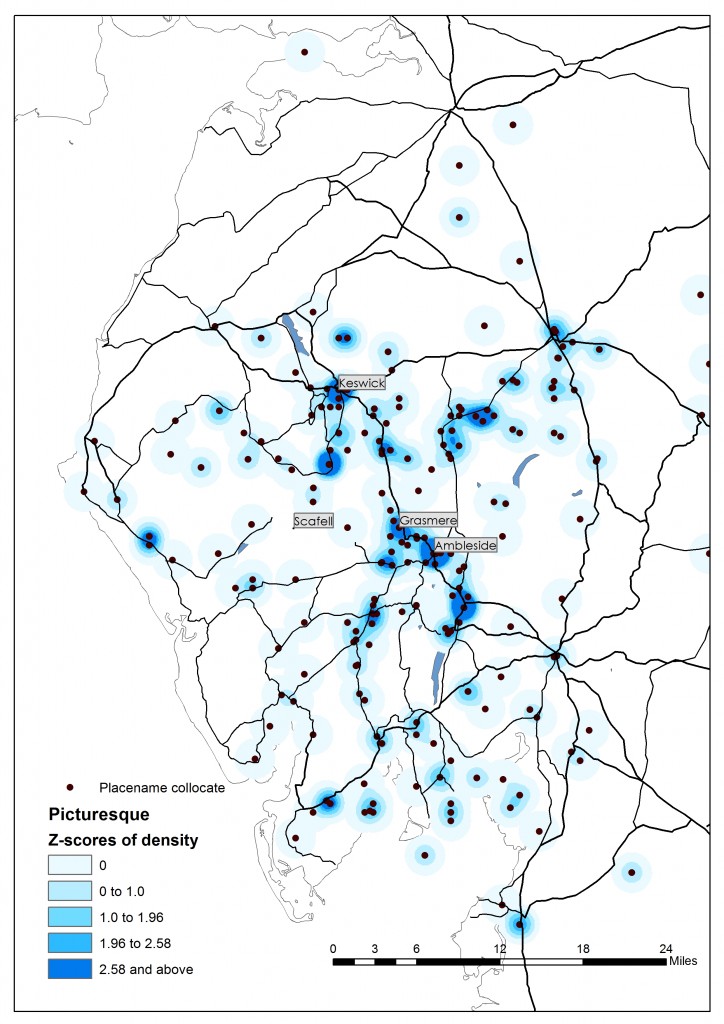

But even though we were already aware that these words were significant, plotting the distribution and density of the places they collocate with has given us a much clear sense of the areas throughout the Lake District with which they are most commonly associated (figure 2).

Figure 2. Maps displaying the places that collocate with picturesque, beautiful and sublime in the corpus of Lake District writing. Click on each map to enlarge.

What’s perhaps most intriguing about what we’ve discovered is that whereas picturesque and beautiful most frequently occur in relation to places near principle tourist centres, such as Grasmere, Ambleside and Keswick, places that frequently collocate with sublime fall both near Keswick also in the region around Wasdale Head, which contains Scafell Pike, Scafell and Great Gable (3 of the 4 highest mountains in England). Observing this pattern has helped reinforce our impression that the word sublime is frequently associated with dramatic, mountainous terrain.

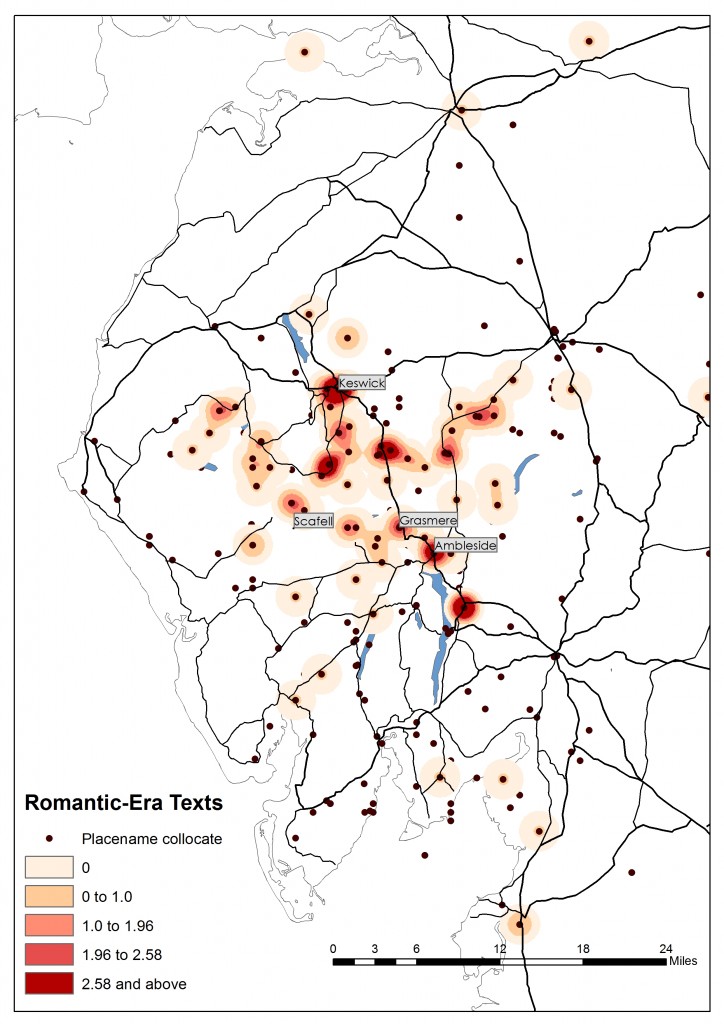

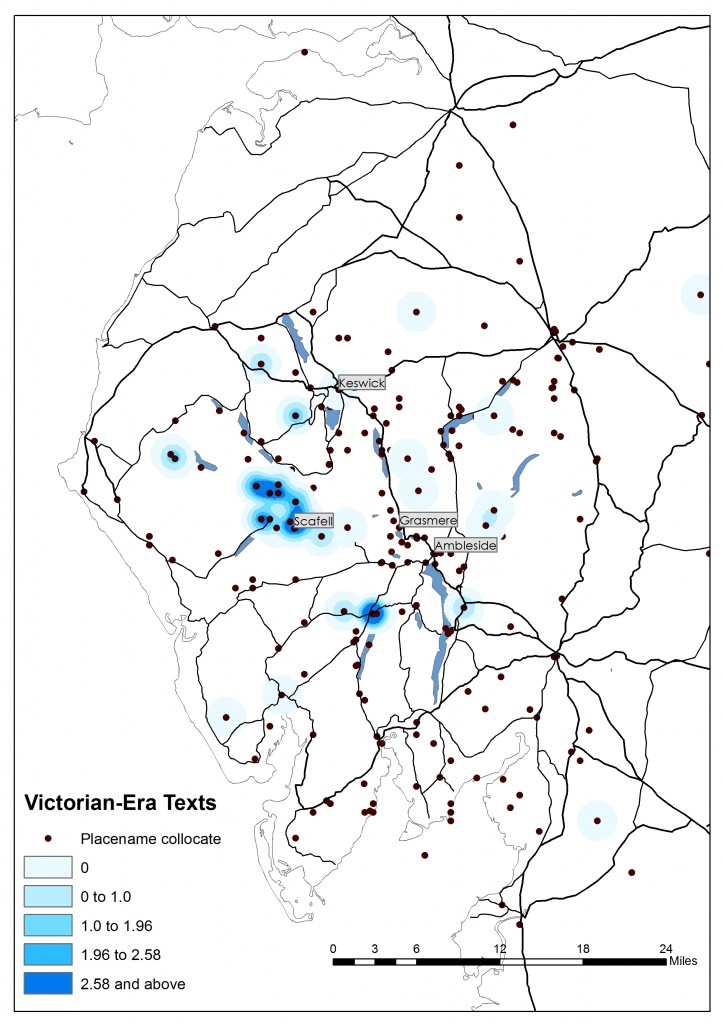

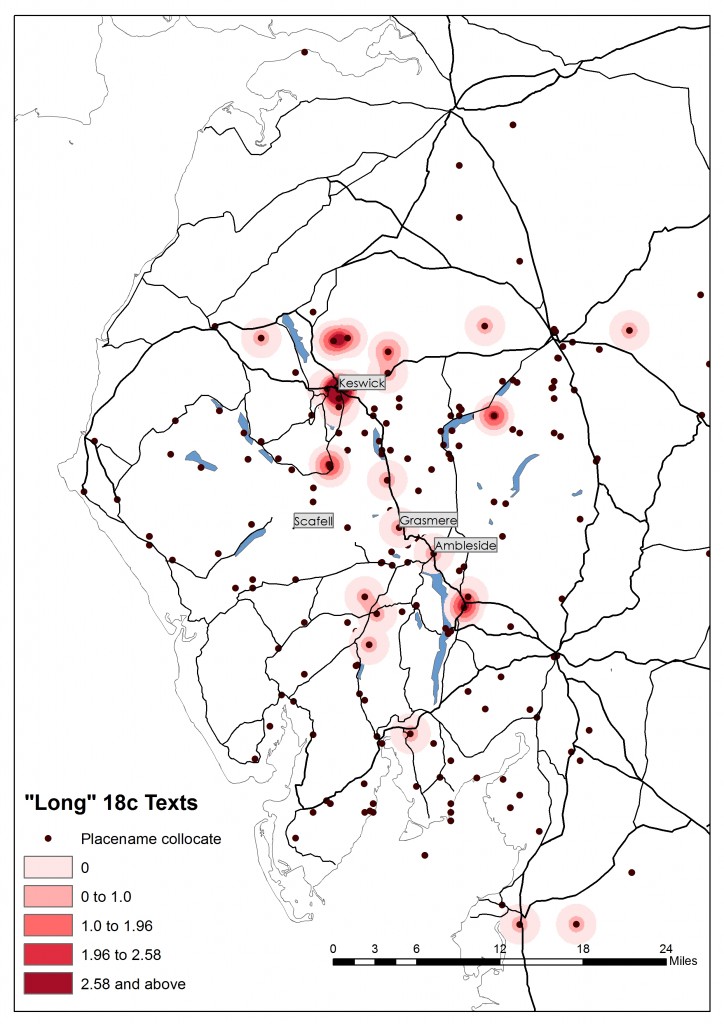

This impression is further reinforce when we consider the places that collocate sublime in each of the historical sub-periods in our coprus (figure 3). As you can see, it is not until the Romantic and, especially, the Victorian period that sublime begins to collocate with places in the western part of the Lakes. Although there are different potential explanations for this, it seems most likely that it’s related to the fact that mountaineering did not emerge as a major tourist activity in the Lake District until the mid- to late- nineteenth century.

Figure 3. Maps displaying the places that collocate with sublime in the three sub-periods of the corpus: the ‘long’ 18th century (1622-1797), Romantic Era (1798-1836) and the Victorican Era (1837-1901). Click on each map to enlarge.

Figure 3. Maps displaying the places that collocate with sublime in the three sub-periods of the corpus: the ‘long’ 18th century (1622-1797), Romantic Era (1798-1836) and the Victorican Era (1837-1901). Click on each map to enlarge.

This work is still on-going; so we’d be keen to hear your feedback about our initial findings. Please write to us.