|

The Strip Map

The Roads invade the County Maps

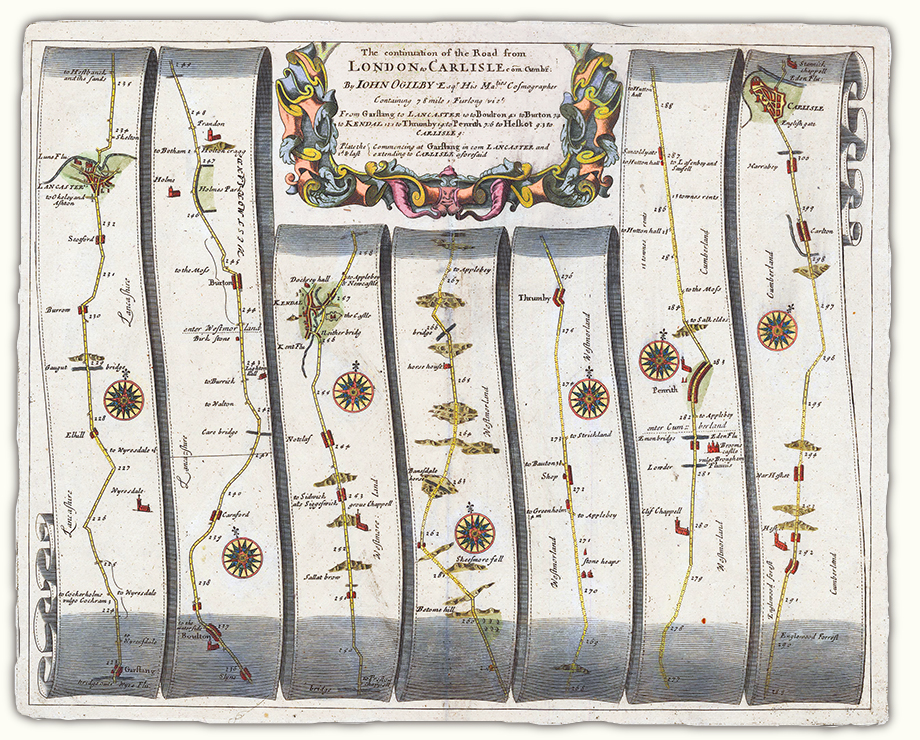

The road map was first popularised by John Ogilby (1600-1676), Scotsman, dancing master (until his accident), Deputy Master of the Revels, publisher, and cartographer, who published his Britannia in 1675. This showed all the main routes radiating from London, together with a handful of cross-country routes (e.g. York to Lancaster, Carlisle to Tynemouth, Oxford to Cambridge). Like the old Automobile Association personalised route-maps, they are strip maps which concentrate on the roads, orienting the traveller with a compass rose, and showing side roads, landmarks, and the type of terrain, hills to be surmounted and rivers to be crossed. The scale was a standard inch-to-a-mile. The maps are very large, 415mm wide x 329mm high, and the pages they are printed on even larger: it is difficult to imagine anyone other than a well-attended gentleman using them in transit.  John Ogilby Britannia (1675) map 38: Garstang to Carlisle. Though this is not as well known as the maps are, he also provides written information about the distances, terrain, 'Backwards turnings to be avoided', the major places of interest, market days, and whether the traveller is likely to find suitable 'entertainment', i.e. hospitality. This is Ogilby on Kendal: Kendal, a fair, large and well-frequented Town, esteem'd the Beauty of the County, pleasantly seated on the River Can or Kent, of no great Antiquity, but remarkable Industry, exercising great Manufacture of Cottons, Druggets, Hats, Stockings, &c. has a large Church to which belongs 12 Chapels of Ease, and on the East-side of the River stood formerly a Castle, whereof the Ruinous Walls now only remain: It is Govern'd by a Mayor, 12 Mayors-Peres or Aldermen, 12 Common-Councel Men, a Recorder, &c. near the Church stands a fair Freeschool well endow'd, with Exhibitions to Queen's College in OXFORD: It has a great Market on Saturdays, and 2 Fairs annually on the 25th of April and 28th of October, and between those Terms a great Beast-market every Fortnight. His views of the route from Kendal to Carlisle through the Lake District via Keswick were less sanguine: it is in General as bad a Road as any in England, being very Hilly, Stony and Moorish, where you seldom meet with that Entertainment as in the more Frequented Roads in the Midle of the Kingdom. The routes he shows would have been familiar to Fox, though Fox also moved off the main roads. In his journey from Swarthmoor to Carlisle he went round the edge of the Lake District, presumably availing himself of the 'entertainment' provided by Friends. For a fullsize image of this map, go to

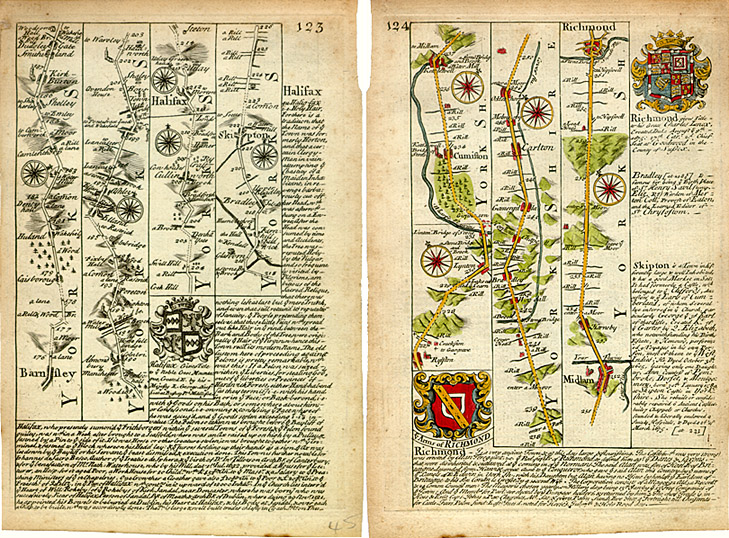

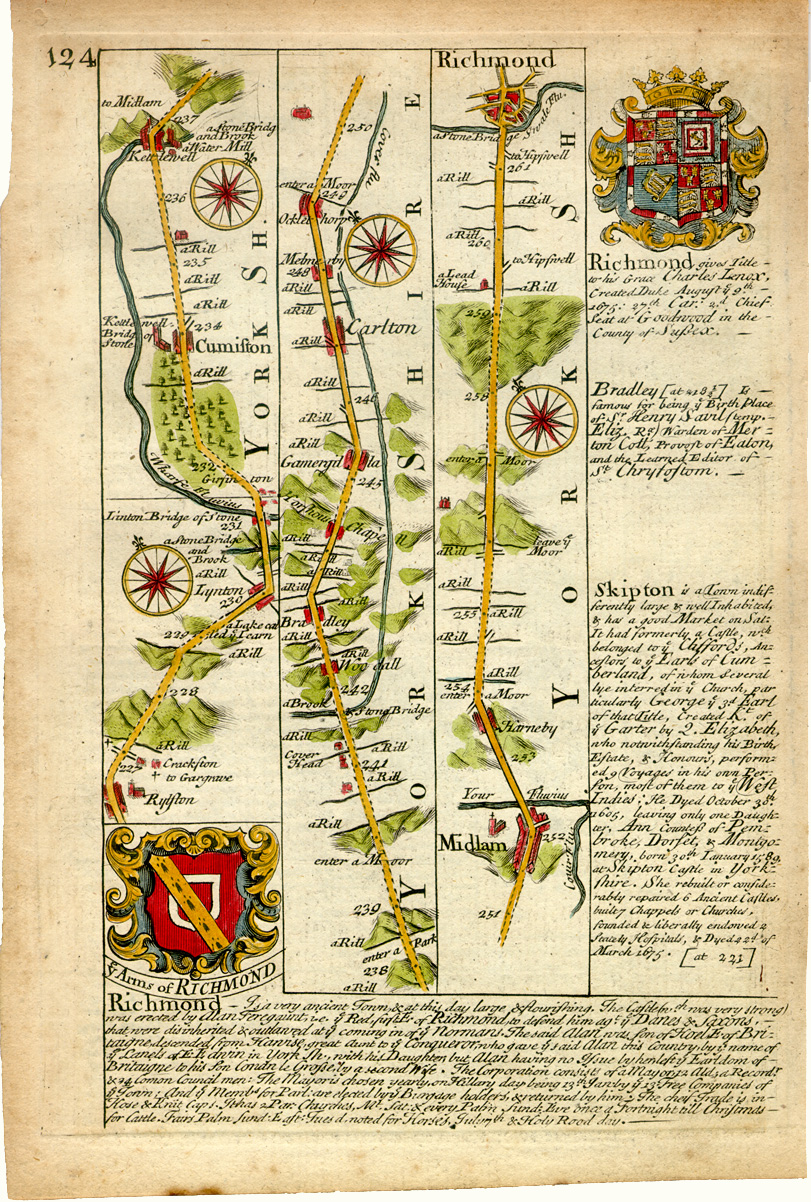

The Old Cumbria Gazetteer by Martin and Jean Norgate, a treasure-mine of information, images of maps, and topographical writings on the Lake District. John Senex, a distinguised geographer, cartographer, and explorer, published a reduced-size (c. 20cm x 15cm), version of Ogilby's maps in his Actual Survey of all the Principal Roads of England and Wales (1719). He incorporates the distances in the cartouche at the top of each map. Ogilby's road maps were 'improved' by John Owen & Emmanuel Bowen (1694–1767), in their Britannia Depicta or Ogilby Improved (1725). They also reduced them to a manageable travelling size: these cropped pages are 137mm wide by 220mm high. Bowen was responsible for engraving the 272 strip maps, and Owen, the antiquarian, the topographical information. They printed the useful information for travellers supplied by Ogilby alongside the maps on the same page, adding further historical notes, coats of arms (to be coloured in), and descriptions of the nobility and gentry associated with the area: for example, the entry below on Skipton (last column of page 123: the town actually appears on the map on the previous page) waxes eloquent about Lady Anne Clifford. It gives a much stronger impression of being intended for tourists, whether practical or armchair.  John Owen and Emmanuel Bowen Britannia Depicta or Ogilby Improved (1725),

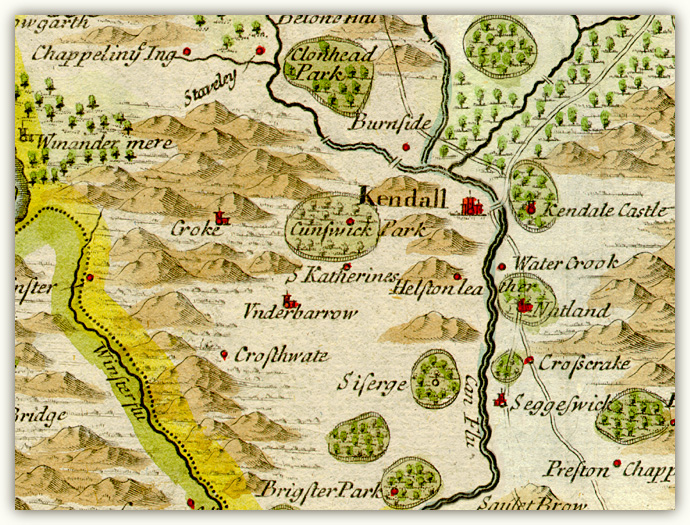

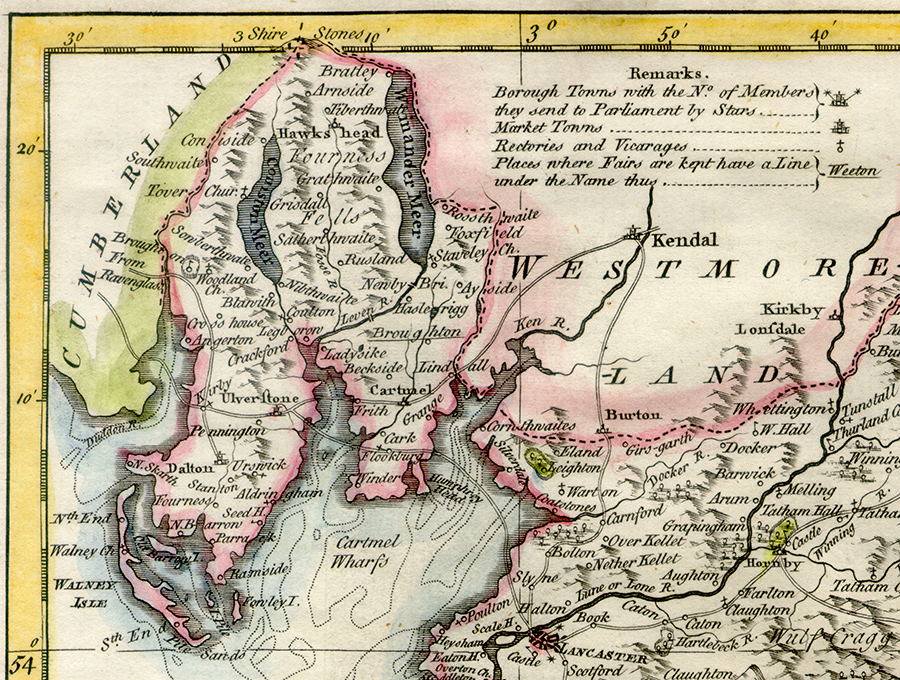

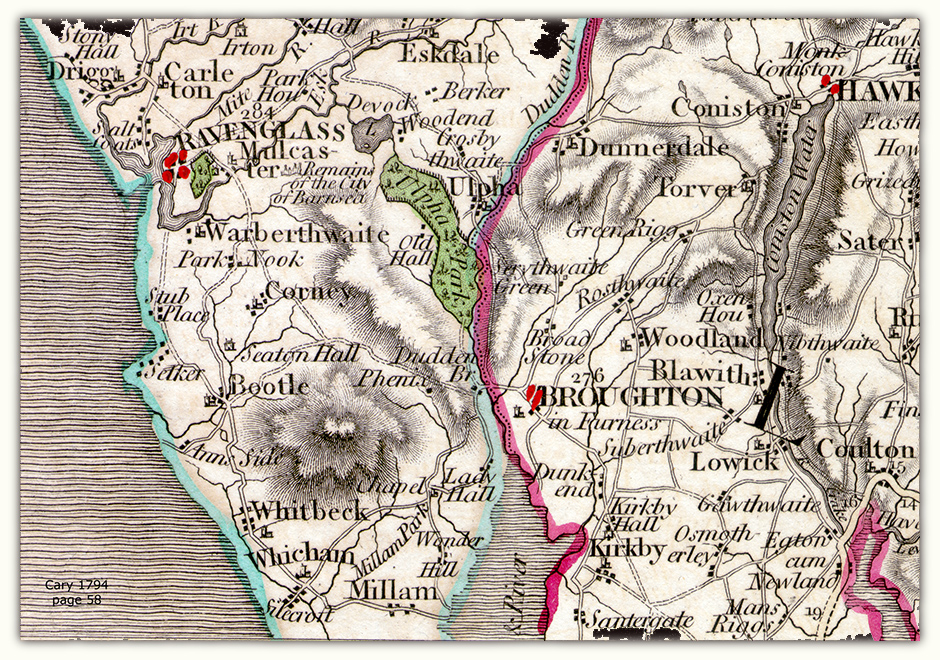

pages 123–4: Image © Meg Twycross 2008 Maps based very closely on Ogilby's 1675 Britannia: the only alterations are a slight rearrangement of the placing of the captions, and the omission of the words ‘a Vill’ alongside towns and villages. Larger version of page 124  John Owen and Emmanuel Bowen (1725), after John Ogilby (1675): Route from Skipton to Richmond Image © Meg Twycross 2008 Robert Morden (d. 1703), geographer, cartographer, and practical scientist, was the first to include roads in his county maps published in the 1695 edition of Camden's Britannia by Edmund Gibson. He took them from Ogilby, however, so they only show the main roads from London and the few cross-country roads Ogilby had surveyed. They are portrayed as narrow double lines, and could almost be missed altogether; county boundaries (the heavy dotted lines) are much more prominent. Gibson's preface explains that: The Maps are all new engrav'd, either according to Surveys never before publish'd, or according to such as have been made and printed since Saxton and Speed. Where actual Surveys could be had, they were purchas'd at any rate; and for the rest, one of the best Copies extant was sent to some of the most knowing Gentlemen in each County, with a request to supply the defects, rectifie the positions, and correct the false spellings. And that nothing might be wanting to render them as complete and accurate as might be, this whole business was committed to Mr. Robert Morden, a person of known abilities in these matters, who took care to revise them, to see the slips of the Engraver mended, and the corrections, return'd out of the several Counties, duly inserted. Upon the whole, we need not scruple to affirm, that they are by much the fairest and most correct of any that have yet appear'd. And as for an error here and there; whoever considers, how difficult it is to hit the exact Bearings, and how the difference of miles in the several parts of the Kingdom perplex the whole; may possibly have occasion to wonder, there should be so few. Especially, if he add to these inconveniencies, the various Spellings of Places; wherein it will be impossible to please all, till men are agreed which is the right. I have heard it observ'd by a very Intelligent Gentleman, that within his memory, the name of one single place has been spell'd no less than five several ways. sigs A4r-4v. His local informants did much improve the accuracy of the placenames: thus Natland has ceased to be 'Notclaf' as it was in Ogilby.  Robert Morden Britannia (1695): 'Westmorland', between cols 804 and 805: detail of roads round Kendal. Here there is no sign of the road going west from Kendal to Underbarrow and eventually Ulverston, since Ogilby does not show it; nor, though Ogilby's version of the road west to Windermere and eventually Keswick is shown, does Morden show any way of reaching Ambleside from Kendal to join it. He does however include Ogilby's roads from Egremont to Cockermouth and Carlisle in his Cumberland map. It seems likely that Fox followed the Egremont to Brigham road. Richard Blome does not show roads in his original version of Speed's Maps Epitomiz'd: or the Maps of the Counties of England (London: 1681), but by the time Richard Taylor reissued them in 1715 as England Exactly Described (London: Taylor, 1715), he seems to have copied Morden, and the Ogilby routes appear. .From now on integration was only a matter of time. Thomas Kitchin (1719–1784) was apprenticed to Emmanuel Bowen and married his daughter Sarah, though he set up business as engraver (of portraits as well as maps) and publisher on his own. His Small English Atlas (1749) is a county-based collection showing an elaborate network of major and minor roads. The larger format of his Large English Atlas, produced in collaboration with Bowen between 1749 and 1760, allowed him to include other features such as terrain and elegant vignettes of typical local scenery. Kitchin's Post-Chaise Companion (1767/1770) is a collection of strip-maps after Senex.  Thomas Kitchin: Detail from A New Map of Lancashire drawn from the Best Authorities (1764). The county is still shown not over-supplied with roads, but the main road from Kendal to Ulverston via Underbarrow (on the Westmorland map) and Cartmel is clear, and so are the routes across the sands. There has been some attempt to show the sandbanks and channels, both in Morecambe Bay and acros the Duddon Estuary. .John Cary (1754-1835) had extensive hands-on experience of measuring roads. He worked on the Ordnance Survey from 1780, and in 1794 was appointed ‘Surveyor of the High Roads from London’ for the GPO. His New and correct English atlas: being a new set of county maps from actual surveys, exhibiting all the direct & principal cross roads, cities, towns, and most considerable villages, parks, rivers, navigable canals &c. ... Also a general description of each county, and directions for the junction of roads from one county to another 2 vols (London: printed for John Cary, 1787) is in the traditional format of the county map, but shows minor as well as major roads (though they tend to run into the sand in Cumberland). His 1790 Traveller's Companion is in the strip-map format. The breakthrough from our point of view comes in his 1794 Cary's New Map of England and Wales: with Part of Scotland. On which are Carefully Laid Down All the Direct and Principal Cross Roads, the Course of the Rivers and Navigable Canals, Cities, Market and Borough Towns, Parishes, and most considerable Hamlets, Parks, Forests, &c. &c. Delineated from Actual Surveys: and materially assisted from Authentic Documents liberally supplied by the Right Honourable the Post Master General (London: J. Cary, 11 June 1794), which does exactly what it says on the tin. Moreover, it is the first to attempt the format to which we have become accustomed: it rejects the county layout for a grid of 81 continuous pages which could (with a few irregularities) be laid to edge to edge to cover the entire country, if one wished. We have now entered the age of turnpikes, and need to be careful before extrapolating backwards to Fox's era, but for the first time we can see in this part of the country not only major but minor roads which were important routes, especially in the age of pack-horses. He also shows contours in a recognisable way.  Detail from map 58 of Cary's New Map of England and Wales (1794). This not only shows the contours of the Furness Fells and Black Combe, it also shows the network of small roads across the fells from Ulverston, and what is now the green ride round the back of Black Combe to Bootle, a plausible route for Fox to have gone from Kirkby in Furness and Miles Wennington's Ash House at the head of the Duddon Estuary. (It actually also appears in Kitchin's Cumberland.) Cary is famous for having used copper engraving while many of his fellow cartographers were moving on to the harder-edged steel. |