When I was a teenager, I wrote fanfiction. I also wrote a fair amount of original work, but most of it was fanfiction. The longest single piece of fanfiction I wrote was probably bigger, word-wise, than my PhD thesis will eventually end up being. (136,000 words, six months to write, if you’re wondering).

I mention this because I learned a lot from it – not least, how to use proper grammar and sentence structure – but especially because the world of creative writing was the first place I ever encountered the emotional ‘stretch’ associated with large-scale self-motivated projects. At first I was pretty terrible at things like keeping myself on track and maintaining a coherent plan and getting words on paper even when I wanted to curl up and die of anxiety and shame at how terrible my work was. But as I bounced from one story to another, the projects I undertook getting more coherent and complex each time, I knew I was on an upward trajectory heading… somewhere, I guess?

Then I got into university and the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos sacrificed my creative heart on the altar of problem sheets and examinations. But that’s a story for another time.

Now I stand on the brink of a new phase of my life, with an awful lot more maths know-how and relevant industrial experience and a respectable research topic direction, but many of the emotional struggles of my daily life are very familiar from my teenage fanfiction days. I recently attended a workshop organised for the STOR-i MRes cohort entitled “Building Resilience and Tackling your Inner Critic” and delivered by the amazing Tracy Stead. Most of what follows is my notes from that workshop, tidied up and interspersed with my own thoughts on the subject.

The leaky bucket model of motivation

Tracy introduced a metaphor that I particularly like: the idea of motivation and confidence as a bucket with holes in. Though the bucket is always draining, certain things drain the bucket faster, and certain things fill it up. It’s nearly impossible to do productive work when the bucket is close to empty. Therefore, we should make sure to keep the bucket topped up and avoid poking additional holes in it – that way, we’ll be more productive overall.

According to the 2019-20 STOR-i MRes cohort, these things drain the bucket:

- Conflicts with other people

- Code doesn’t work, I don’t know why or how to fix it

- When I forget what I’ve read or how to do something ‘basic’.

- Working alone without people who I can talk to that understand what I’m doing.

- Seeing a really good piece of academic work and thinking “I couldn’t possibly measure up to this, so why am I even trying?”

These things, however, top it up:

- Talking to someone supportive

- Getting good results, or quick wins

- Taking a break and doing something else for a while

- Breaking new ground, starting a new project

I note that the only thing that fills the bucket that is both under conscious control (we can’t have research breakthroughs on command) and isn’t ‘do something else’ involves talking to someone. Maybe STOR-i is onto something with its philosophy of “A PhD is not a solo activity”.

Tracy’s “official” answer to the question of things that fill the bucket (or build resilience) is organised into a five-point plan (and I love myself a good five-point plan):

- Relationships – cohorts “part of a team”, networks “people find me valuable”, supervisors “I can ask for help”, getting outside perspective on my problems so they don’t seem so bad,

- Optimism – focus on the future not the past, goals and milestones and visions, figuring out: who do I want to be? Continuously striving for improvement

- Coping skills – build confidence, lead a healthy lifestyle, make your rituals and habits productive ones, minimise unwanted stressors in your life.

- Competence – invest in skills and problem solving, experience, knowledge.

- Emotional intelligence – If I notice, name, choose, and communicate my emotions, that will help me think more rationally about things.

Meetings with Supervisors

I am a naturally anxious person, and especially so around other people. I absolutely dread meetings with my supervisors. (Sorry Idris & Paul if you’re reading this – it’s not you, I swear, you’re both lovely). My internal monologue in the lead-up to a meeting can get incredibly distorted and critical. This is Tracy’s titular inner critic, and is a problem definitely shared in various degrees by many of the MRes cohort. Here are some of the things our inner critics say about meetings with supervisors:

- I might say something stupid.

- I haven’t done enough this week and my supervisors will think I’m lazy.

- The supervisors might think I’m a mistake and I’m not good enough for this project.

- I’m not prepared for this meeting.

- Why haven’t I come up with any good ideas?

- I should know the answer to this.

- What I’ve done didn’t work, so it’s useless and there’s no point sharing it.

Tracy talked about re-framing each of these distorted thoughts into positive to build our motivation (fill that bucket!) and help us move forward.

- What I’ve done didn’t work, so it’s useless and there’s no point sharing it. What hasn’t worked is a stepping stone towards what will work, so it’s good to share it.

- I should know the answer to this. The meeting is an opportunity to learn from an expert. The point of being here is to learn.

- Why haven’t I come up with any good ideas? It’s going to be great to talk about this with someone who understands the field. It’ll probably help me come up with good ideas.

- I’m not prepared for this meeting. This meeting is not a viva and my supervisors are not grading me on the quality of my preparation or performance.

- The supervisors might think I’m a mistake and I’m not good enough for this project. This stuff is actually really hard and the only reason my supervisors find it ‘easy’ is because they’ve been here a lot longer than me. They know that and they’re not expecting perfection from me.

- I haven’t done enough this week and my supervisors will think I’m lazy. I like my supervisors and it’s good to talk with them, especially during those times when I’m unmotivated and unproductive.

- I might say something stupid. I am definitely going to say something stupid. My supervisors will hopefully correct me. This is a good thing.

A Song About Lit Reviews

I don’t just write stories. I also write and perform poetry and songs. (If you meet me in person and want to put me in a good mood, give me a ukulele and ask me to sing you the song about hiding the dead bodies – it’s one of my favourites).

I have recently started becoming acquainted with the literature in the field of anomaly detection. This has inspired the following song, to the tune of 99 bottles of beer:

99 papers on my to-read list

99 papers to read

Get through one, skim the references

127 papers on my to-read list.

“Projects” are constrained and time-bound. They have deadlines and well-defined stages and a (mostly) linear sense of progression. If you’re off-track or off-schedule, something is wrong. Contrast with “research” which is inherently expansive and messy, where going off-track is pretty much the norm and progression happens in jolts and lightbulbs interspersed with periods of what can at the time seem like aimless drifting through an ever-expanding mass of awful. (At least, that’s what the second-year PhDs tell me – they call it the “valley of shit”).

The Creative Diet

To get through this valley with sanity intact, Tracy asks us to pay attention to our environment around us, and design a ‘diet plan’ of daily activities designed to top up our motivation and creativity. Here’s what I came up with:

- Exercise: in the morning and during breaks

- Talk to people doing similar things, to enhance and refine your own perspective.

- Spend time being bored: your mind wanders and you have new ideas.

- Randomness and lack of routine. Breaking up habits.

- Meditation, meditative activities (colouring books, cleaning)

- Hold yourself accountable to self-imposed deadlines by telling other people about them.

Other Thoughts

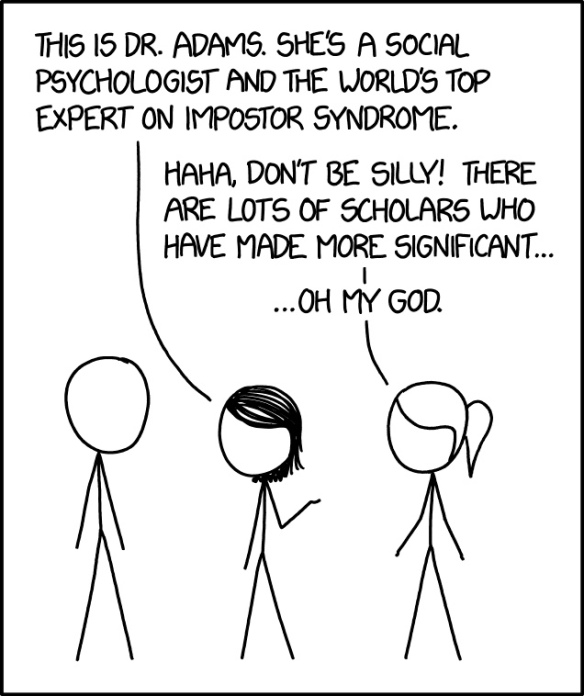

Tracy covered a lot more than I’ve written about: impostor syndrome, task prioritisation, how to reflect and learn from experiences in a healthy way rather than dwelling on the negatives, etc. Here are two thoughts I had about writing that cropped up during the rest of the workshop that don’t relate much to anything I’ve said before:

- Software. The brain was not actually designed to write documents in a linear fashion on a computer. We’re hampered so much by Microsoft Word and everything that looks like it (yes, this includes LaTeX) in ways that we don’t realise until we try something different. In my teenage years, I used Scrivener to organise my writing and thoughts in a heavily non-linear fashion. I’ve heard it’s pretty bad at rendering maths, though, so I’m on the lookout for better options for the PhD life.

- Cycles of inspiration and criticism, drafting and re-drafting. You can’t edit an empty page. First drafts don’t need to be perfect. Creativity and perfectionism are antagonists, mood-wise. You need both, but you should separate them so they don’t screw each other up.