Yet another reason why COVID is not the flu

With multiple vaccine Phase III trials coming back with promising interim results, I’d like to take a moment to talk about a bias in statistics called “survivorship bias”, and how it can skew our thinking.

Wikipedia’s definition of survivorship bias is as follows:

“Survivorship bias or survival bias is the logical error of concentrating on the people or things that made it past some selection process and overlooking those that did not, typically because of their lack of visibility. This can lead to false conclusions in several different ways. It is a form of selection bias.”

Usually, survivorship bias causes us to be unreasonably optimistic. For instance, a meta-analysis of scientific studies in a field will often produce more evidence supporting a hypothesis than is actually true, because the studies that didn’t find any evidence for that hypothesis never got published (shout-out to the Journal of Articles in Support of the Null Hypothesis for doing what it can to address this problem).

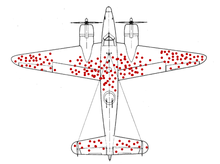

Sometimes survivorship bias can lead us to damaging conclusions. For example, look at this picture of what parts of planes got shot on WW2 air raids, and think about there you would put armour on the planes if you could edit their design.

The obvious (and wrong) answer is to put armour on the parts of the plane with the most holes so it will stop the most bullets. The correct answer, of course, is to put armour on the bits of the plane without bullet holes, because planes that got shot in those places didn’t make it back to be counted.

So how does this apply to COVID-19?

Here, the “people or things” we are interested in are infectious diseases. And the “selection process” is not getting relegated to the history books by the development of a successful vaccine. The battleground of public health is littered with these kinds of corpses. Mumps, rubella, tetanus, polio, whooping cough, smallpox… and yet there are also survivors, like HIV and influenza and measles.

Because HIV and influenza and measles are survivors, they’re the ones we hear about in the papers. And because of that, they’re the ones we unconsciously consider in the back of our minds when weighing up probabilities, including probabilities of success for vaccine development and deployal. COVID has been compared a lot to the flu, for example, but not much if at all to polio (despite the fact that the 2020 pandemic has revived iron lungs as ventilator substitutes in countries that don’t have enough of them).

But each of HIV, influenza, and measles has a reason why it hasn’t been consigned to the history books. They are, in summary (and with apologies for the oversimplifications):

- HIV infects by getting eaten by the immune system and then slowly destroying it from the inside, so the standard vaccine idea of “make the immune system eat it quickly before it causes disease” is a non-starter, and most vaccine trials for HIV fail because of this (some even make things worse).

- Influenza mutates really, really fast. It doesn’t have the “check your work for mistakes” proteins many other viruses do, having sacrificed them and the advantages they bring in favour of an infection strategy specifically based around mutating enough to infect the same people over and over. It’s so far been impossible to develop a vaccine that the flu can’t mutate its way around, though we have a good crack at it every year.

- Measles is super duper infectious. Remember how everyone’s been talking about the R rate for COVID which is about 3 in a normal population (without social distancing and the like)? The R rate for measles is about 15, which is far higher than any of the other diseases we have vaccines for. This means that even though we have a vaccine, we need to have 95% coverage to stop measles causing outbreaks, and the presence of just a few people who can’t or won’t get vaccinated stops us from getting rid of it for good.

Enter COVID, stage left, November 2019. COVID is an infectious and dangerous disease, so in estimating how it will behave, we unconsciously compare it to the other infectious and dangerous diseases most prominent in the back of our minds. This leads us to an overly pessimistic outlook because of survivorship bias, which is a nice change from the usual.

Truth is, the answer to the question of “why haven’t we eradicated covid yet?” is probably “we haven’t had the time”, rather than something more substantial preventing successful development and deployment of a vaccine. This is borne out by the interim trial results, which report that the standard way of vaccine making works far better for COVID than it does for, for instance, HIV. COVID has “check your work for mistakes” proteins, so it mutates much more slowly than the flu, and we’re not seeing anywhere near the amount of reinfection that would cause us to be seriously worried on this front. And with an R rate of 3, we only need about 75% vaccine coverage to wipe COVID out from society, so the antivax movement isn’t really big enough (yet) to present a COVID-related health problem.

Hopefully, as this pandemic gets mopped up, we’ll see less comparing COVID to the flu, and more comparing COVID to polio, in the graves of the history books where it belongs.