Few people have stopped to consider not only the amount of plastic they rely on - from the toothbrush you use in the morning to the water bottle on your bedside table - but also the different types of plastic that feed into this problem. In trying to blindly tackle this issue, without an understanding of how we need to break down the chemical components that we have used to build plastics in the first place, we have got ourselves tangled in a sticky situation.

There are seven ‘types’ of plastic, used across household and industrial contexts, which can be easily identified by their relative strength, density and usage - you may want to try memorising them by associating each type of plastic with a household / consumer product. For starters, we were mystified when we discovered that only ‘bottle-shaped plastics’ can be recycled in Lancashire - but it is not the shape that is restricting, but rather the type of plastic. In the case of ‘bottle-shaped plastics’, or rather Polyethylene Terephthalate (PETE), the polymer chain that makes the plastic breaks down at a relatively low temperature, which means that less energy and money is consumed in the recycling process. Until more complex systems can be developed to break down the more complex polymer structures in other types of plastics, Lancashire will only have a market for recycling PET.

Recycling household plastic waste in Lancashire is a process that can be identified at various steps; initially, all plastic residuals are collected by the Borough and City Councils within Lancashire and transmitted to the respective local Transfer Station. From there, plastic waste is transported to Waste Processing Facilities across Lancashire, where it is baled and sold to various recycling companies (none of it is sent abroad to be processed). Thanks to Green Lancaster and Lancaster University Student Union, and in collaboration with Lancashire County Council, we had the opportunity to visit both Middleton Waste Transfer Station and Leyland Household Waste Processing Facility. For example, the Waste Processing Facility at Leyland receives ‘bottle-shaped’ HDPE-coloured, HDPE-clear, PET-coloured, PET-clear and mixed plastic.

So, why is ‘bottled-shaped plastic’ the only plastic that is recyclable in Lancashire? This is because the County Council cannot risk contamination of the plastic stream with the wrong type of plastics, and in turn risk an increase in expenditure. By asking the public to throw only "bottled-shaped plastic" in the recycling bins, they ensure that only PETE plastic will be collected, which, as we saw in the graphic up above, is one of the easiest types of plastics to recycle. At present, the council cannot afford any expansion of their facilities for more plastic recycling. Lancaster City Council is currently in discussions on the potential implementation of mixed plastic recyclables collection points at the Household Waste Recycling Centres across the County, which will be delivered straight to recycling companies and therefore will not affect County Council capacity. Household Waste Recycling Centres like Salt Ayre in Lancashire, are otherwise known as ‘bring sites’. Here citizens can dispose of large items or recyclables that have not been collected through the normal process on doorsteps. Not only does this take pressure off local authorities, but also gets the citizen actively engaged in recycling issues.

Part of the problem is a lack of education surrounding waste, plastics and appropriate disposal. Councillor Gina Dowding of Lancashire County Council cited Germany as a brilliant example of education ingrained in culture and social practice, as knowledge of types of plastics and appropriate recycling practice is commonplace. In Germany, supermarkets have started a plastic bottle return scheme, which incentivises appropriate disposal of plastics through financial reward - and it has worked a charm, for plastic-bottle-waste is at an all-time low, at only 1% to 3% of bottles not being recycled. ‘We’ve got used to thinking of plastic as something that will look after itself’, says Councillor Dowding.

Part of the problem is a lack of education surrounding waste, plastics and appropriate disposal. Councillor Gina Dowding of Lancashire County Council cited Germany as a brilliant example of education ingrained in culture and social practice, as knowledge of types of plastics and appropriate recycling practice is commonplace. In Germany, supermarkets have started a plastic bottle return scheme, which incentivises appropriate disposal of plastics through financial reward - and it has worked a charm, for plastic-bottle-waste is at an all-time low, at only 1% to 3% of bottles not being recycled. ‘We’ve got used to thinking of plastic as something that will look after itself’, says Councillor Dowding.

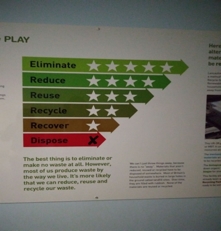

Education is the first step; council-backed initiatives such as Recycle Week, which took place in late September in Lancashire are a good gateway to informing the public about how their habits or behaviours can be changed. However, plastic pollution is a symptom of a wider problem, according to Councillor Dowding. The advisory group that she chairs has the remit of reducing the usage of single-use plastic, but also has the aim of challenging throwaway culture overall. Even at the Recycling Centre in Leyland, the overwhelming advice was to eliminate all waste altogether for minimal environmental impact, demonstrated through the graphics on their walls. So, while it may be great to now offer paper straws instead of plastic straws, we must begin to pose ourselves the difficult question of whether, unless we have specific mobility needs, we need straws altogether.

On an even larger scale, this social practice also needs to be shaped and supported by local authorities, national governments and economies. The complexity of current recycling systems in Lancashire is in itself a deterrent to citizens - the District (i.e. the Borough or City Council) is responsible for collection, while the County is responsible for disposal, and commercial businesses and schools have to organise their own waste collection altogether. Councillor Dowding and her working group are therefore pushing to ‘unravel’ this labyrinth in favour of a ‘uniform system’ that is less confusing and can be interwoven into citizens’ daily practices.

Let’s finish with a simple economic principle: as price increases, demand decreases. If, then, the price of disposing to landfills - which is where single-use plastics end up - is increased, businesses and local councils might be more obliged to reconsider their disposal practices, and by extension, their haphazard use of single-use plastics. With legislation of this sort tackling disposal, and the EU single-use plastics ban tackling production, single-use plastics will gradually be squeezed out of consumer culture. As for Lancashire, the basic infrastructure to effectively and efficiently recycle plastics is already in place; but a mixture of citizen responsibility and economic incentives, coupled with the correct legislation, is needed to ensure that we can move beyond bottles.

By Pentland Centre Champions 2018-19 Maria Zani and Sharlene Gandhi

Photo above taken at Leyland Material Recovery Facility by Maria Zani

Pictured top right, upper picture: Sharlene Gandhi graduated from Lancaster University with a BSc in Marketing Management and French in 2018, and currently works at IBM as a public sector consultant. Her Twitter handle is @Sharlene_Gandhi.

Pictured top right, lower picture: Maria is currently studying Accounting and Finance at Lancaster University Management School.