Mitigating wellbeing pressures in remote and hybrid working models

Posted on

The Covid-19 pandemic has driven a lasting change in how we work. Recent Work Foundation analysis found that 85% of those who worked remotely during the pandemic want to combine remote work with some days at the office, often termed a ‘hybrid’ work model. Whilst the shift to remote work has allowed many organisations to continue operating during the pandemic, it has increased the time that is spent working through digital technologies, with a significant impact on workers’ stress and well-being.

Switching on – but are we switching off?

Previous work conducted by Lancaster University Management School’s Dr Pecis on the impact of technology on work-life balance, coupled with recent Work Foundation findings on the impact of remote working, indicate that any wellbeing impacts of remote working will not remain confined to the pandemic, but are linked to the changing ways in which work is undertaken and managed. Findings from these two pieces of research show that working remotely impacts significantly on work-life balance, in both positive and negative ways.

The shift to remote work has meant that work is brought home and can be done after traditional working hours. Some of us may have found ourselves late in the evening getting back to those emails we did not manage to go through during the day. For some, this is considered in a positive light, as it gives a greater feeling of ‘staying on top of things’ and therefore a greater feeling of control over work activities. However, this can lead to the separation between work and home becoming increasingly tenuous, with work interrupting home activities and vice versa. There are many amusing examples of children interrupting BBC presenters over the course of the pandemic. However, the cognitive effort to go back to a work activity increases after an interruption, and so do the stress and personal conflicts that arise from this.

The 3-minute commute means that some feel they are living at the office

One of the often-discussed advantages of remote work is that commuting is no longer needed, freeing up workers’ calendars and allowing more flexibility in managing work from virtually anywhere. Particularly working parents who shifted to remote working during the pandemic valued the increased time they were able to spend with family. However, the possibility of working anytime from anywhere implies a constant connectivity that has some drawbacks.

Both Dr. Pecis’ and the Work Foundation research projects (among other research) reveal that IT use can increase work intensity, heighten technostress and consequently lead to decreased work productivity. Remote work intensifies the need to be responsive and connected beyond standard working hours, during evenings, weekends and holidays. While some appreciate knowing what is going on in the virtual office at all times, others find that the inability to unplug and switch off is putting strain on their mental wellbeing. One interviewee told the Work Foundation that “it’s not so much working from home, it’s living at work.”

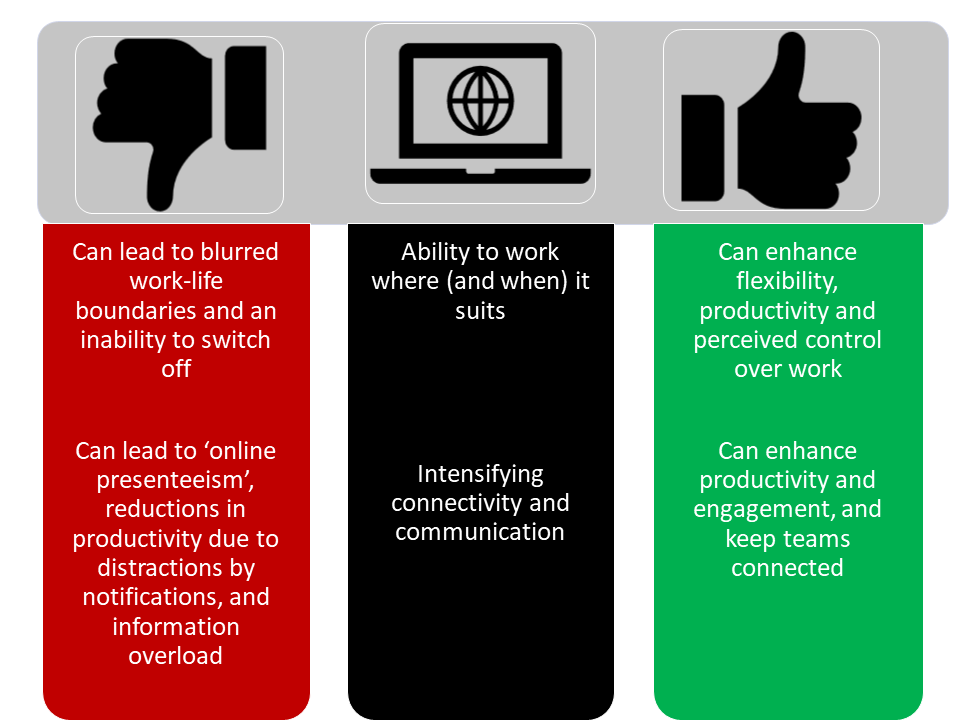

Figure 1: Potential positive and negative impacts of remote work and mobile devices

Considerations for employers

To avoid undue pressure on workers while maintaining the advantages that remote work affords, some countries have stipulated a legal right to disconnect. For example, French law allows companies with over 50 employees to negotiate the right balance in mobile device use and switch off and aims to reduce the intrusion of work into employees’ private lives. In the UK, some companies have started addressing the need for workers to switch off. One company in the North of England told the Work Foundation they had banned meetings between 12 and 2pm to allow for proper breaks and to combat videocall fatigue. Another company has asked managers not to send emails during weekends to avoid putting pressure on their staff to read them out of hours.

Whilst regulating the use of IT devices might help prevent an always on culture, it is imperative that organisations do not roll back the flexibility gains that have been made during the pandemic. Getting this right might require a period of experimentation in which employers and employees try out, and keep, what works. Managers and employers have an important role in fostering an environment in which there is scope for experimentation and open dialogue around arrangements that work best for individuals and their wider teams.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing