Millions on Universal Credit face barriers to accessing training

Posted on

At this point in the pandemic, the benefits system is playing a very different role than we anticipated. Because of support like the furlough scheme, the unemployment rate has remained much lower than had been forecast when Covid-19 first hit the UK. But the number of people getting Universal Credit (UC) has increased sharply since the onset of the crisis. Meanwhile, some sectors face major labour and skills shortages, and Government departments still struggle to work collaboratively to address barriers to training for unemployed people and low income workers.

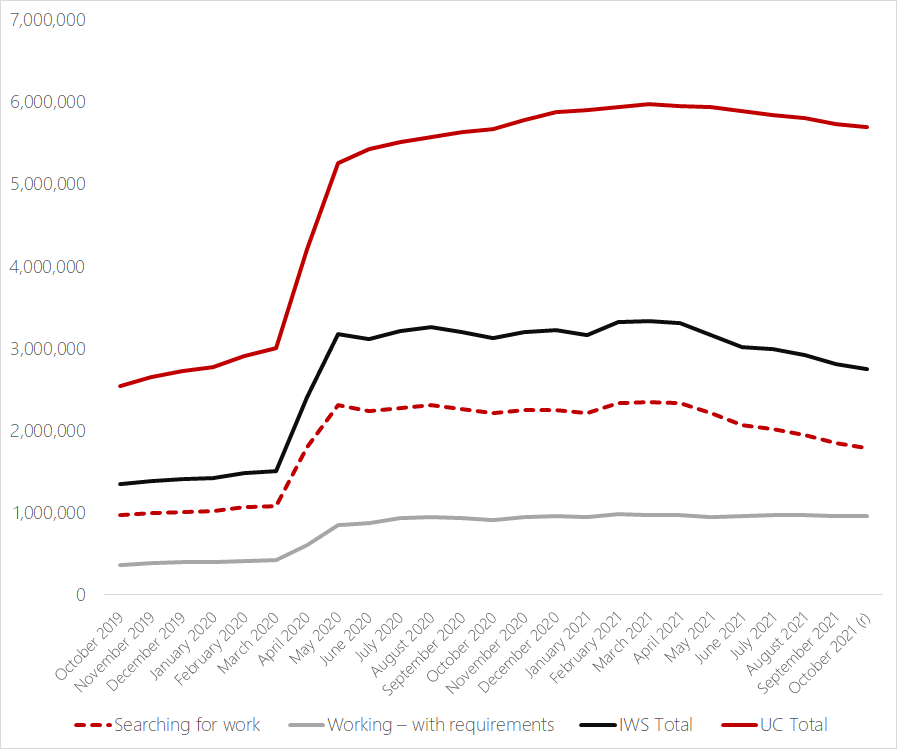

UC combined different benefit systems into one to support both unemployed people and workers on low incomes. Under UC, people who are considered available to work face strict requirements, known as ‘conditionality,’ meaning they must spend up to 35 hours per week looking for work. Individuals in this ‘intensive work search group’ (IWS group), have to provide evidence of their work search to their Job Centre Work Coach and be available to attend meetings with them and job interviews to continue getting UC. The number of people on Universal Credit has more than doubled since October 2019, and this is reflected by a similar increase in the IWS group.

Figure 1 People on Universal Credit between October 2019 – October 2021

Source: Work Foundation calculations using Department for Work and Pensions Stat-Xplore – People Claiming UC, searching for work and working – with requirements. October 2019-October 2021. October 2021 figures are revised.

For some people, meeting these requirements can feel like a full-time job in itself. And the costs of not meeting these requirements are very real, including a risk of loss of benefits. These risks disincentivise UC recipients from undertaking training and lock people out of potential opportunities to improve their career prospects.

As of October, nearly 2.8 million people were in the IWS group and therefore face barriers to accessing training because of rigid requirements built into the benefits system, yet people in this group would stand to benefit the most from training.

Understanding how the IWS group is changing

· Many more people on UC are in work than before the pandemic

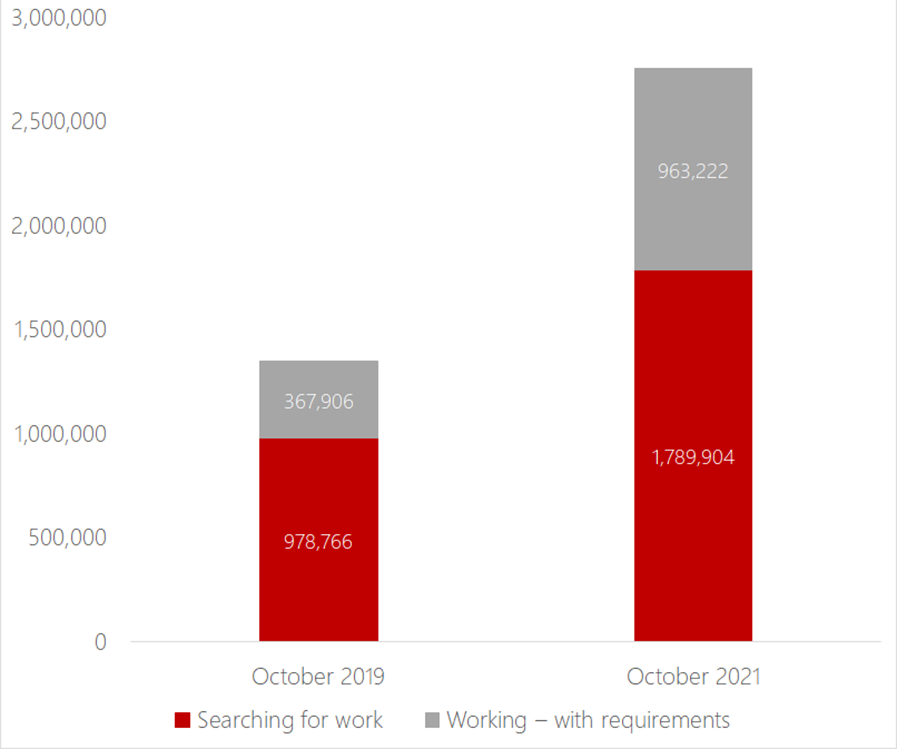

As was the case before the pandemic, most people in the IWS group are unemployed. But the number who are working has grown sharply and now stands close to one million. The proportion of people in the IWS group who are working increased from 27% before the pandemic to 35% in October 2021.

Figure 2 People on Universal Credit – Intensive Work Search Group 2019 vs 2021

Source: Work Foundation calculations using Department for Work and Pensions Stat-Xplore – People Claiming UC, searching for work and working – with requirements. October 2019 and October 2021. October 20201 figures are revised.

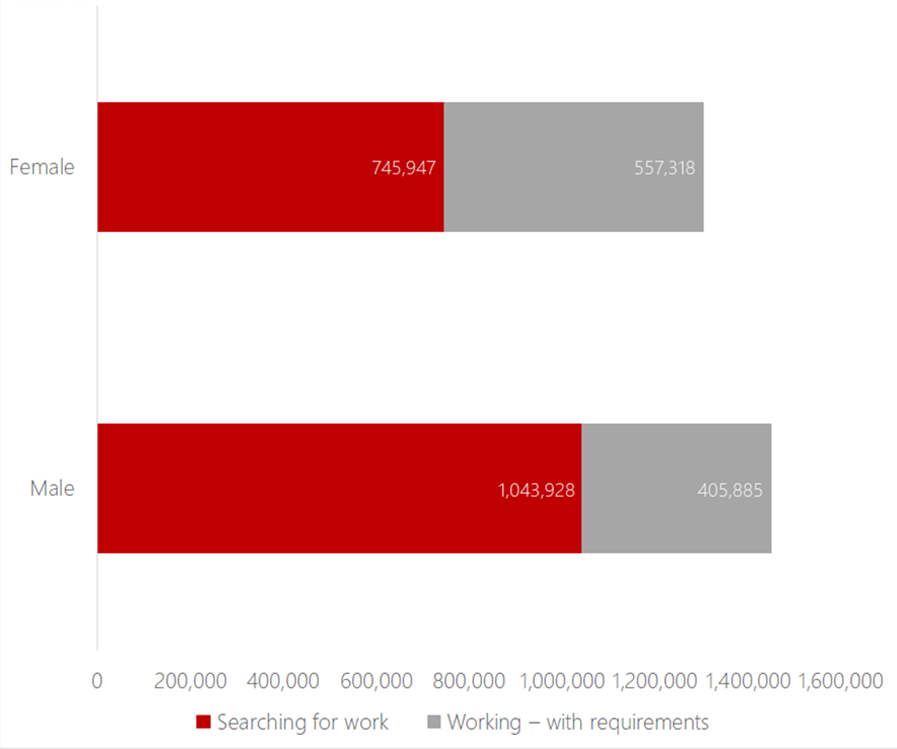

· Women in the IWS group are more likely to be in work than men

Men continue to make up a larger portion of the IWS group overall (as was the case pre-pandemic), but most men in the group are unemployed and looking for work full time (72%). In contrast, women are more equally split between those looking for work (57%) and those who are working.

Figure 3 People on Universal Credit – Intensive Work Search Group by Gender – October 2021

Source: Work Foundation calculations using Department for Work and Pensions Stat-Xplore – People claiming UC, gender, searching for work and working – with requirements. October 2021 revised figures.

What does this mean for policy?

The UK benefits system should be enabling rather than hindering access to training opportunities. In the context of the economic recovery, it is vital that Government prioritises supporting the greatest number of people who would benefit from training to access these opportunities, and that must include people receiving UC.

Programmes like the Skills Bootcamps and Restart will be especially important for helping unemployed and low wage workers upskill and retrain. But individuals receiving benefits still face barriers to accessing training opportunities. Although the new Train and Progress initiative introduced greater flexibility for those on UC to pursue 12 and 16-week full-time training courses, this support is due to end in April 2022. In the first instance, it is vital this policy is extended beyond this cut off point.

But with a greater proportion of the IWS group in work and unable to participate in full-time training, many in the IWS group could face barriers to accessing intensive training through schemes like the bootcamps. Previous Work Foundation research has highlighted challenges in navigating training alongside childcare and caring responsibilities that parents, and often women in particular, face. Therefore, focusing on part-time, flexible and modular training may prove more effective in widening access to training in future.

While it’s too early to tell how successful the Skills Bootcamps have been, initial evaluation figures suggest provision has not met demand. While only 820 people took part in the first wave of bootcamps, 2,500 people applied, a fraction of the number of people in the IWS who could benefit from training.

In this context Government should ensure that the funding is in place to increase capacity to meet demand so that everyone who could benefit from the training has the opportunity to. And Government should look into expanding the eligibility criteria for the Skills Bootcamps to allow people on Universal Credit who’ve been unemployed for longer than 12 months to access them.

In the new year, the Work Foundation is undertaking research into the barriers faced by UC recipients trying to access training. As part of this work we will be speaking directly with people on UC about their experiences of accessing training programmes. If you’d like to speak to us about this research to learn more, please do get in touch with Olivia Gable at o.gable@lancaster.ac.uk.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing