“Unpaid minutes are a sign of the times”: financial insecurity in the gig economy

Posted on

© Photo by Joshua Lawrence on Unsplash

© Photo by Joshua Lawrence on Unsplash

The Covid-19 pandemic prompted a surge in demand for courier and food delivery services in the UK. However, apps that cater to customer convenience can come at a cost for delivery workers. This way of working is highly financially insecure, particularly for workers who derive their entire earnings from the gig economy. In addition to being unpredictable, pay can be extremely low. Recent research from Lancaster University highlights how unpaid waiting time plays a significant role in lowering average earnings for bike couriers and suggests new avenues to shift power to couriers.

Financial risk rests with the gig worker

Many couriers and food delivery drivers are classed as self-employed. This means they are responsible for buying, maintaining and, where relevant, fuelling their own vehicles. Most delivery work is paid per drop, rather than per hour. Even though the piece rate may be adequate, ancillary costs coupled with unpredictable demand can result in low pay. Last year, analysis of pay data for 300 Deliveroo Riders by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism found that a third earned below the UK minimum wage. Some workers earned as little as £2 per hour on average.

Given the impact the cost of living crisis is already having on some gig economy workers, it is important to take a closer look at one of the key drivers of financial insecurity: unpaid waiting time.

New research aims to shift power into couriers’ hands

Lancaster University academic Oliver Bates has been conducting research into the gig economy through two primary research projects:

- Switch-Gig[i] — a pilot study aiming to design technology that meets couriers’ needs and communicates their lived experiences.

- FlipGig[ii], a multi-year, multidisciplinary project working with both gig economy couriers and businesses who use these kinds of workforces. It involves collecting new data on couriers’ working lives, developing new models which are grounded in fairness, , and provide tools to flip power dynamics for couriers. This innovative project collected anonymised jobs data and GPS data, and conducted interviews with eight gig economy couriers focusing on unpaid working time during summer 2021.

Paid and unpaid working time

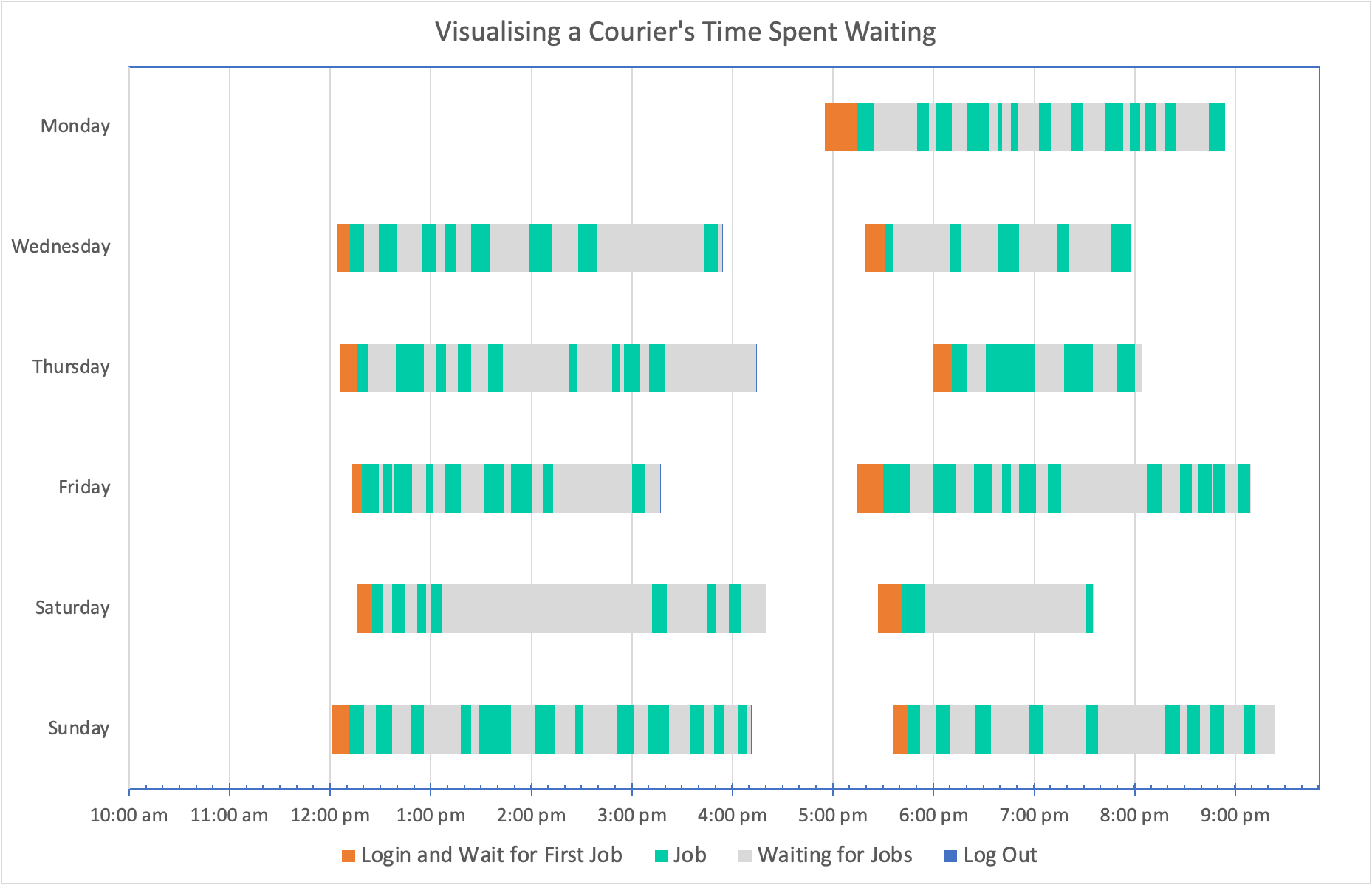

Data collected through the FlipGig project provides insight into couriers’ working patterns. It shows the number of jobs couriers undertook, how long they were logged onto the platform and how much of that time was spent waiting, and the substantial variation in hourly pay that workers experienced.

The figure below illustrates a working week for one of the participants, demonstrating the wide variation in time spent on deliveries and waiting for jobs.

Fig 1: Visualisation of waiting time for one courier during one week in 2021

Uncovering worker strategies for optimising earnings and taking control

Without having insight into the platform’s algorithm that allocates them jobs, workers build up tacit knowledge on the job, such as when and where to work, where to wait for jobs, what work to reject, and how to protect their safety, earnings and reputation — and this is vital for taking what control they can over their work.

Couriers feel a pressure to accept jobs to make enough money, but the more experienced workers reject orders strategically. They ensure that they select a string of jobs that start near to their current location, don’t take them too far away from the central restaurants so they can more quickly pick up the next job, and, unless necessary to make enough money, don’t take jobs where there might be unknown restaurant delays.

The Switch-Gig project captured how couriers use technology to record evidence when things go wrong on jobs, such as orders that disappear out of the system and result in loss of pay.

Some bicycle riders take photos to keep records of incidents, and others use activity tracking apps such as Strava to collect data that is useful for understanding their workday, as well as challenging the platforms when something goes wrong[i].

Mitigating financial insecurity in the gig economy

Unpaid waiting time is a highly contested issue across the wider economy, for example in the social care sector. However, it is particularly problematic for gig workers. Despite couriers’ efforts to develop an understanding of the platform algorithm and undertake steps to maximise their earnings, unpaid waiting time is an innate fixture of the gig economy. One interviewee spent their waiting time carrying out mobile IT work. But no amount of multi-apping or strategic rejection of jobs will change the unpredictable and insecure nature of gig work.

Consumers have a role to play in ensuring the platform economy becomes fairer. For example, they may opt to order through platforms that organisations such as Fairwork indicate are more likely to provide gig workers with decent jobs.

But achieving systemic change requires we move beyond an individual approach. The courts play an important role in tackling insecurity for gig economy workers. For example in 2021 the Supreme Court ruled that Uber drivers were workers rather than self-employed contractors. This meant Uber became obliged to pay at least the national minimum wage to its drivers, including during time spent waiting for a job.

However, recourse through the courts can take a very long time and may not find broad implementation across the platform economy. There is an opportunity for Government to revise how gig economy workers are classified and clarify the rights and protections they can access through the forthcoming Employment Bill. Building on recommendations in the 2017 Taylor Review and proposals gathered through the 2018 employment status consultation, this should be informed by workers’ experiences and preferences, and set a clear ambition to improve job quality in the gig economy.

[i] Kirman, B., Bates, O., Lord, C., Alter, A. (2022), Thinking outside the bag: worker-led speculation and the future of gig economy delivery platforms. Conference paper. DRS 2022: Bilbao 25-26 June. Available: https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/167031/2/DRS2022_paper_SwitchGig_cameraready_submitted.pdf

[ii] Bates, O., Alter, H., Friday, A., Kirman, B. (2021), Lessons from one future of work: opportunities to flip the gig economy. IEEE Pervasive Computing, Vol. 20(4), pp. 26-34. DOI: 10.1109/MPRV.2021.3113825

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing