Take fashion; whilst the ready availability of clothing has led to the formation of a nefarious industry, with some time and care, one could ensure that they are only investing in sustainable clothing. Similarly, with transportation, it is not implausible to perceive a culture in which personal and family cars are ditched in favour of bicycles and public transport.

Food, on the other hand, is fundamental to human existence and therefore, conversations around food sustainability can often end up becoming emotive and highly divisive. The Sustainable Development Goals pushing for ‘Zero Hunger’, ‘Good Health and Wellbeing’, and ‘Responsible Consumption and Production’ are in direct competition with an ever-growing global population, and consequent higher food demands and pressures on agricultural industries. Amidst such conflicting values, how can we begin to have a productive, meaningful conversation around food practices?

The Lancaster Environment Centre’s Sustainability Group hosted the 2050 Food Week in the Michaelmas term, a five-day event covering food packaging, food choices, and the climate change impact of the food and agriculture industries. Participants had the opportunity to not only learn about the impacts of their own food footprints, but also make a pledge about what they may want to change about lifelong food habits. 2050 Food Week was the second-part of a series of 2050 events hosted by the research centre, exploring different ways in which we will attempt to meet our reduction commitments in 31 years’ time - 2050 Travel Week took place earlier in the term.

The event recognised the interconnectivity between different stakeholders present in this particular realm. Not only is food essential to all human consumers, but it is also vital for local businesses to understand that they can have a pioneering role in the sustainable food dialogue. Lancashire small business greats, Atkinson’s Coffee and Stephenson’s Dairy, were interwoven into the 2050 Food Week Agenda to bring their perspectives to the table.

2050 Food Week was the first step to exploring how the Lancaster community, through local action, could make a tangible positive impact on the food and agriculture industry. The aspiration would be for the actions of the Lancaster community to filter out into the national and global communities, as we all need to be aligned in making such large-scale changes to culture and social practice.

__________________________________

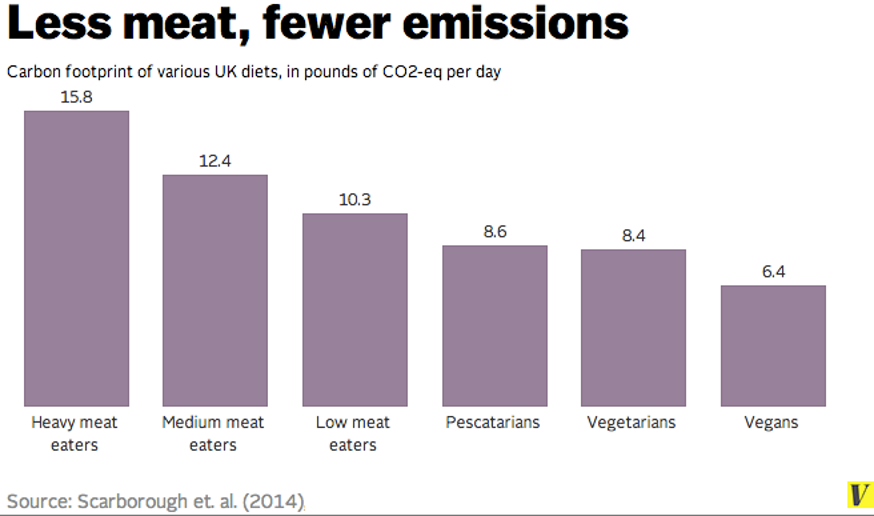

Alan Warde remarks in the Oxford Handbook of Consumption that food is a fundamental component of national identities, cultures and upbringings. Knowledge about meat and fish providing vital proteins, and dairy being essential for growth and bone strength, is imparted upon children in schools, and recipes passed down through generations without eyelids batted. But it is vital that this information is reshaped, because it feeds into a multitude of issues surrounding sustainability, such as nutrition poverty and water wastage – according to a framework commissioned by The Lancet journal, we will have the resources to feed 10 billion people healthy diets by 2050, but this model is delicately balanced on the assumption that people will consume little to no red meat or diary. However, changing food habits is akin to challenging well-entrenched traditions, often bringing tensions into households as families can no longer eat the same meals if one individual decides to take a step in a sustainable-diet direction. Whilst most might shy away from bringing conflict to the dinner table, Casey Seidenberg highlights why there is no reason that the whole family cannot get involved in becoming more food conscious, and in fact, use it as a tool to spark discussion and debate: ‘Name a soup’, she says, ‘and I bet it can be made without meat. And who says a burger has to be ground beef?’ A study by Scarborough et al (2014) showed that converting to a vegetarian diet can halve individual carbon dioxide footprints, whilst veganising has a footprint of only a third of that of a heavy meat diet. Many at 2050 Food Week made a pledge to explore these alternative diets.

In a similar vein, a shift in perspective is needed on what we class as clean, healthy and consumable food. Documentary filmmaker Nelufar Hedayat embarked on a journey of discovery in her eight-part docuseries, Food Exposed, revealing shocking statistics and imagery about the extent to which food is wasted if it is not ‘beautiful’ enough for the Western supermarket stall. In one particularly memorable instance, Hedayat strolls around a local food market in South America with her guide, who points her towards some blackened, short bananas. British consumer Hedayat is taken aback that this kind of produce is sold at a local market, like any other British consumer would be. Her guide then reveals a perfectly ripe and perfectly edible banana under the skin. We may think that the ‘pretty food’ trend is something that has come with the rise of Instagram, but this industrial culture of sending a sanitised version of food to the West has long been at play. Morrison’s Wonky Fruit and Veg initiative aims to bring light to this wasteful practice, and with shoppers coming to terms with their own fallibility, the scheme is proving commercially lucrative.

The final, all-encompassing point of discussion is around food packaging. We have all seen the ludicrous photos of foods with natural encasing - bananas, coconuts, avocados - being covered again in plastic for no good reason other than convenience of the customer. With yet more plastic available in the form of bags at the end of the till, supermarkets have been accused of creating more than 800,000 tonnes of plastic waste per year. The steady cropping up of zero-waste shops is an answer to this, but they present yet another challenge to consumer culture: where the plastic in the supermarket allows the consumer to ‘forget’ bags and containers at home, the zero-waste shops compel the consumer to slow down, plan ahead and bring the necessary vessels with them to fill to their heart’s content. So is the consumer to blame for their laziness, or the supermarket for their willingness to continue to feed this laziness with yet more plastic packaging?

__________________________________

Food’s complexity comes not only from its essentiality and emotiveness, but also from its industrialisation and the difficult fact that it forms the backbone of so many national economies. As 2050 Food Week at Lancaster University has done, conversations around food sustainability must go beyond the environment and consider economic and social sustainability too, a feat that transcends the remits of any one kind of research department or governmental body. That said, as research by The Lancet highlights, it is imperative that we ‘integrate food systems into international, national, and business policy frameworks’ in order to achieve what seems impossible.

We can all agree that we need food. But do we need the pomp, the plastic, and the perfection around food?