|

Travellers

Click on the thumbnails for photo-credits and further links.

‘A ii. mile from Lancastre the cunteri began to be stony, and a litle to wax montanius.’ 1

‘There was an English woman had something to declare from the Great God to the Great Turk.’

We can supplement the information from Fox’s Journals from the accounts of other travellers who covered the same ground and left memoirs and accounts, sometimes intended

for publication, sometimes for purely private consumption. They colour in the rather sparse picture of the terrain Fox draws with the kind of details one expects — road conditions, scenery, buildings,

places of interest, and so forth. The kind of information we get from them will naturally depend in the reasons for their journeys and for writing them up afterwards.

Accounts of travels in the North West of England are the most obviously useful for this particular project. But the early Quakers

lived in an age of travel. The discovery of the New World had had an impact similar to that of putting the first men on the Moon — with

this difference, that once the transport infrastructure was in place, it was possible for ordinary people to go there. Within four years of the events in this part of the Journals, Henry Fell from

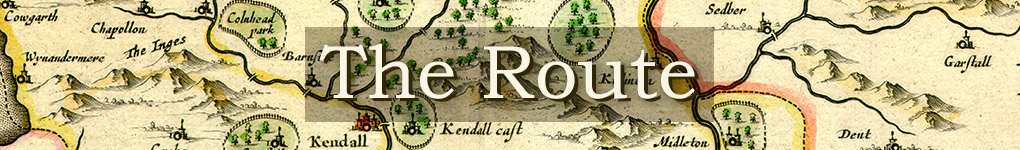

Lancashire North of the Sands was setting off from Bristol, financed by Friends, to spread the message in Barbados. In 1658, Mary Fisher

from Selby in Yorkshire (who was with him in Barbados, and then went on to Boston (Mass), where she and her older companion were accused of witchcraft, imprisoned, and deported back to Barbados)

was in Adrianople (Edirne) in Turkey. There she was received most courteously by the 16-year-old Sultan Mehmed IV, who listened to what she was moved to say, ‘and desired her to stay in that Countrey, saying —

That they could not but respect such a One as should take so much pains to come to them so far as from England with a Message from the Lord’. It says a great deal

for the Grand Turk that he was as, if not more, willing to listen to a (female) ambassador from God as he was to a Swedish embassy the previous year,2 whereas

her fellow Christians’ reaction in America was to strip-search her for marks of witchcraft. We have to fit the local journeying of 1652-1653 and its evidences into the larger picture, or our image of it

becomes distorted. It does not matter whether they had read Hakluyt’s Voyages: it was in the air they breathed. Accounts of travels in the North West of England are the most obviously useful for this particular project. But the early Quakers

lived in an age of travel. The discovery of the New World had had an impact similar to that of putting the first men on the Moon — with

this difference, that once the transport infrastructure was in place, it was possible for ordinary people to go there. Within four years of the events in this part of the Journals, Henry Fell from

Lancashire North of the Sands was setting off from Bristol, financed by Friends, to spread the message in Barbados. In 1658, Mary Fisher

from Selby in Yorkshire (who was with him in Barbados, and then went on to Boston (Mass), where she and her older companion were accused of witchcraft, imprisoned, and deported back to Barbados)

was in Adrianople (Edirne) in Turkey. There she was received most courteously by the 16-year-old Sultan Mehmed IV, who listened to what she was moved to say, ‘and desired her to stay in that Countrey, saying —

That they could not but respect such a One as should take so much pains to come to them so far as from England with a Message from the Lord’. It says a great deal

for the Grand Turk that he was as, if not more, willing to listen to a (female) ambassador from God as he was to a Swedish embassy the previous year,2 whereas

her fellow Christians’ reaction in America was to strip-search her for marks of witchcraft. We have to fit the local journeying of 1652-1653 and its evidences into the larger picture, or our image of it

becomes distorted. It does not matter whether they had read Hakluyt’s Voyages: it was in the air they breathed.

Travel Writing

Travel writing3 is a genre in its own right, but it comes in many kinds. At the ‘crafted’ end, it is a branch of literature, but it can be reportage or spoof, non-fiction or fiction. Then there are journals, whether written up with

an eye to publication or not. They may contain descriptions or reactions, or just give a simple itinerary. If they give dates, we can work out how long it took on average to get from one place to another. The same goes for

(financial) accounts and other non-literary documents. All these serve the practical end of helping us to visualise what his journeys might have been like, and how long they might have taken.

It should also be possible by comparing all these different types of document to determine whether Fox was consciously writing in a particular genre. Are the Journals travel-writing or life-writing, or

a blend of both? (See The Journals for a discussion of the contemporary connotations of the word journal.) The popularity of travel-writing partly explains why Yearly Meeting were happy to publish the Journal

in the form they did.

Journeying for God

Ultimately this kind of writing owes its origins to

pilgrimage literature, most of which sought to provide guidebooks not only to the Holy Land itself, but also to the arduous journey there, with tips to intending pilgrims on how to make oneself as comfortable

as possible, how to ask basic questions in all the languages they would encounter along the way, and how to avoid being

cheated in them. The earliest English road-map (1250-1259) is by historian and artist

Matthew Paris and shows the route from London to Jerusalem

and beyond. The opening chapters of Mandeville’s Travels were, curiously to us, one of the most popular

and perfectly serious guidebooks on the Jerusalem journey.4 The runaway popularity of Mandeville also shows that there was an appetite for armchair tourism, especially when

combined with less authentic Marvels. Ultimately this kind of writing owes its origins to

pilgrimage literature, most of which sought to provide guidebooks not only to the Holy Land itself, but also to the arduous journey there, with tips to intending pilgrims on how to make oneself as comfortable

as possible, how to ask basic questions in all the languages they would encounter along the way, and how to avoid being

cheated in them. The earliest English road-map (1250-1259) is by historian and artist

Matthew Paris and shows the route from London to Jerusalem

and beyond. The opening chapters of Mandeville’s Travels were, curiously to us, one of the most popular

and perfectly serious guidebooks on the Jerusalem journey.4 The runaway popularity of Mandeville also shows that there was an appetite for armchair tourism, especially when

combined with less authentic Marvels.

Returning pilgrims were eager to share their experiences:

Margery Kempe was only one of the pilgrims who recounted her travels on her return home. Most pass on helpful information: the Itineraries of

William Wey (?1407-1476) to Santiago de Compostella and Jerusalem, begin with a very useful chapter on exchange rates.5 Though many other guidebooks were doubtless

compiled in libraries rather than on the road, the Italian poet Petrarch (1304-1374) is possibly unique in writing a Guide to the Holy Land which starts with the statement that he sees no chance of ever going there

himself.6

In Protestant England, pilgrimages had been abolished and shrines destroyed, and it is unlikely that Fox and his companions had ever read any of these ‘Romish’ works. They exist merely as evidence of

what seems to be a human instinct to record one’s travels, especially if they feel significant or life-changing. Those with an urge to travel had to find other reasons and goals. In Protestant England, pilgrimages had been abolished and shrines destroyed, and it is unlikely that Fox and his companions had ever read any of these ‘Romish’ works. They exist merely as evidence of

what seems to be a human instinct to record one’s travels, especially if they feel significant or life-changing. Those with an urge to travel had to find other reasons and goals.

Spiritually they never ceased to do so.

The idea that life is a journey, and that we are all ‘strangers and pilgrims’,a travelling

towards a city not of this earth, was too deeply embedded. The people who received Fox’s message called themselves Seekers,

‘For they that say such things [that they are strangers and pilgrims] declare plainly that they seek a country’.b

In 1678, John Bunyan published The Pilgrim's Progress,

in which the hero, Christian, travels from the City of Destruction to the Heavenly Jerusalem, which is only achieved after death. Spiritually they never ceased to do so.

The idea that life is a journey, and that we are all ‘strangers and pilgrims’,a travelling

towards a city not of this earth, was too deeply embedded. The people who received Fox’s message called themselves Seekers,

‘For they that say such things [that they are strangers and pilgrims] declare plainly that they seek a country’.b

In 1678, John Bunyan published The Pilgrim's Progress,

in which the hero, Christian, travels from the City of Destruction to the Heavenly Jerusalem, which is only achieved after death.

Fox’s theology has a different trajectory, and the Journal does not present his travels as that kind of spiritual journey, except at the very beginning. He seems to identify them, and

the missions of the valiant Sixty, with those of the Apostles whom Christ sent out in Mark 6: 7-13. As travel literature, the Journal thus concentrates

on the journey itself, because the goal, to bring the message to and ‘convince’ as many people as possible, is on-going and cumulative. They are also ‘travails’, authenticated by the sufferings

he and they experience along the way. As we shall see, in the literature of exploration, the ‘pilgrimage’ theme re-emerges, unexpectedly, as a justification for colonisation, which is accompanied

by the obligation to spread the Faith, whichever branch of it the coloniser subscribed to.

Journeying for Profit, Diplomacy, and Religion

This is the other archetypal reason for travelling. Merchants travel to markets, or to find new ones. This shades into what

we would consider the literature of exploration. The 24-year journey of Marco Polo (1254-1324) along the Silk Road from Venice to China is the most celebrated of early examples, but there were

other ‘merchants’ relations’,7 recording journeys taken ‘in the name of God

and for profit’.8 Handbooks were published giving exchange rates and the kind of commodities to be bought.

Portolan charts

were drawn for mariners, showing the exact coastlines of the known world, usually based on the Mediterranean, but stretching accurately into the Atlantic as far north as the British Isles and as far south as the

Canary Islands.9 The Age of Exploration, and the ‘discovery’ of America did not come out of nowhere. This is the other archetypal reason for travelling. Merchants travel to markets, or to find new ones. This shades into what

we would consider the literature of exploration. The 24-year journey of Marco Polo (1254-1324) along the Silk Road from Venice to China is the most celebrated of early examples, but there were

other ‘merchants’ relations’,7 recording journeys taken ‘in the name of God

and for profit’.8 Handbooks were published giving exchange rates and the kind of commodities to be bought.

Portolan charts

were drawn for mariners, showing the exact coastlines of the known world, usually based on the Mediterranean, but stretching accurately into the Atlantic as far north as the British Isles and as far south as the

Canary Islands.9 The Age of Exploration, and the ‘discovery’ of America did not come out of nowhere.

It did however give a boost to stories of exploration. Accounts of travel in Europe and the East were always popular,

especially if written in a racy picaresque style. The market leader here was Thomas Coryat

(c.1577-1617), ‘the Odcombian Legg-stretcher’, who travelled, largely on foot, from his home in

Odcombe, Somerset, first round Europe, which he enshrined in Coryat’s Crudities, Hastily gobled vp

in five Moneths trauells (1611), and then, apparently almost by accident, to the Moghul court of Shah Jahangir in India, walking all the way from Jerusalem to Ajmer in fifteen months ‘and odde daies’.

He was not the only English traveller in India: on his way there he met Sir Robert Sherley

and his Circassian wife coming back from the Moghul court with ‘two Elephants, and eight Antlops’

as presents for the Shah of Persia; and when he arrived he was welcomed and put up by ten English merchants of the East India Company,

and was there to greet the arrival of an old friend, Sir Thomas Roe, ‘as an Ambassadour’ from James I and VI on behalf of the same Company.10

Unfortunately Coryat contracted dysentry and died in Ajmer in 1617. It did however give a boost to stories of exploration. Accounts of travel in Europe and the East were always popular,

especially if written in a racy picaresque style. The market leader here was Thomas Coryat

(c.1577-1617), ‘the Odcombian Legg-stretcher’, who travelled, largely on foot, from his home in

Odcombe, Somerset, first round Europe, which he enshrined in Coryat’s Crudities, Hastily gobled vp

in five Moneths trauells (1611), and then, apparently almost by accident, to the Moghul court of Shah Jahangir in India, walking all the way from Jerusalem to Ajmer in fifteen months ‘and odde daies’.

He was not the only English traveller in India: on his way there he met Sir Robert Sherley

and his Circassian wife coming back from the Moghul court with ‘two Elephants, and eight Antlops’

as presents for the Shah of Persia; and when he arrived he was welcomed and put up by ten English merchants of the East India Company,

and was there to greet the arrival of an old friend, Sir Thomas Roe, ‘as an Ambassadour’ from James I and VI on behalf of the same Company.10

Unfortunately Coryat contracted dysentry and died in Ajmer in 1617.

The great anthology of travel writing was Hakluyt’s Voyages. The first edition was published in 1582, entitled Divers Voyages Touching

upon the Discoverie of America, followed by his Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation, which was just in time to record the circumnavigation of the globe by Francis Drake.

An augmented three-volume edition appeared in 1599-1600.11 The Voyages are credited with inspiring the creation

of the English colonies in America, and the setting up of the Virginia Company.

In 1584, he had urged Queen Elizabeth to engage on the colonisation of America, for reasons political, religious, and mercantile.12

This duly followed, as did plantations in the West Indies. John Rous, Fox’s stepson-in-law, who married Margaret, the eldest of the Fell daughters, was born in Barbados, son of a planter, and was convinced there,

probably by Henry Fell, in 1656. He seems to have journeyed to and fro quite regularly, and by 1671 it was unexceptional for Fox to go to Barbados, and then on to Jamaica, Maryland, and Virginia.

The journey was potentially dangerous, cramped, exhausting, and unhealthy, but nothing out of the way.

The first point in Hakluyt’s Discourse on Western Planting (1584), was ‘That this westerne discoverie will be

greately for thinlargemente of the gospell of Christe, whereunto the princes of the refourmed relligion are chefely bounde, amongest whome her Majestie ys principall’.13 After Hakluyt’s death in 1616,

the Rev. Samuel Purchas published a vast continuation, Hakluytus Posthumus, or, Purchas his Pilgrimes (1624-1625). Purchas had already linked exploration with the ‘pilgrimage’ theme,

probably because his earlier work, Purchas his Pilgrimage (1613) was an attempt to combine world history and geography with the history of religions. He justifies exploration (and settlement)

because it spreads Christianity, and English exploration because it spreads true Christianity and not Catholic ‘superstition’. His modern ‘pilgrims’ include John Hawkins, Francis Drake,

Sebastian Cabot, and John Davis.14 This gave English explorers what they perceived as the moral high ground over their Spanish and Portuguese counterparts. The first point in Hakluyt’s Discourse on Western Planting (1584), was ‘That this westerne discoverie will be

greately for thinlargemente of the gospell of Christe, whereunto the princes of the refourmed relligion are chefely bounde, amongest whome her Majestie ys principall’.13 After Hakluyt’s death in 1616,

the Rev. Samuel Purchas published a vast continuation, Hakluytus Posthumus, or, Purchas his Pilgrimes (1624-1625). Purchas had already linked exploration with the ‘pilgrimage’ theme,

probably because his earlier work, Purchas his Pilgrimage (1613) was an attempt to combine world history and geography with the history of religions. He justifies exploration (and settlement)

because it spreads Christianity, and English exploration because it spreads true Christianity and not Catholic ‘superstition’. His modern ‘pilgrims’ include John Hawkins, Francis Drake,

Sebastian Cabot, and John Davis.14 This gave English explorers what they perceived as the moral high ground over their Spanish and Portuguese counterparts.

The 1620 Mayflower settlers were not actually christened ‘Pilgrim Fathers’ until 200 years later, but recently the name has been justified because William Bradford,

their Governor, wrote in his account Of Plymouth Plantation, that some were reluctant to leave Leiden, but were persuaded it was for the best: ‘So they lefte that goodly & pleasante citie,

which had been ther resting place near 12. years; but they knew they were pilgrimes, & looked not much on those things, but lift up their eyes to ye heavens, their dearest cuntrie, and quieted their spirits’.

This however does not refer to their journey to the New World as a pilgrimage, but to the familiar motif that we are all ‘strangers and pilgrims’ in this world. They seem to have accepted

the general view that the land was legitimately there for the taking: ‘those vast & unpeopled countries of America, which are frutfull & fitt for habitation, being devoyd of all civill inhabitants,

wher ther are only salvage [savage] & brutish men, which range up and downe, litle otherwise then ye wild beasts of the same’.

The emphasis is all on the colonists’ right to religious freedom, not the conversion of the ‘savages’.15

Continental Tourism

Closer to home, the Englishman's proverbial love/hate affair with Italy was in full swing, fostered by romances, plays, and travel accounts. Travel was particularly recommended for young courtiers:

Coryat hopes that his European books may ‘may infuse (I hope) a desire to them to trauel into transmarine nations and to garnish their vnderstanding with the experience of other countries’ and languages,

so as to make them more useful to their monarch in diplomacy and war.16 Fynes Moryson (1566-1630), on the other hand, having devoted most of his late 20s to it,

declared roundly, ‘I say the fruit of trauell is trauell it selfe’.17

Catholic Europe also provided the experience of journeying, moderately safely, to observe the practice of an alien religion, given,

as Moryson points out, the proper precautions: ‘There is great art for a Traueller to conceale his Religion in Italy and Spaine, with due wisdome and without offending his conscience’.

18 It even produced spy stories: Anthony Munday (?1560-1633), writer, dramatist, and pageant-master, claimed in The English Romayn Life (1582) to have infiltrated

the newly-founded English College at Rome, where Jesuits were being prepared for the mission to reconvert England:19 though he had taken the precaution of contacting

Cardinal Allen first. (Coryat, on the other hand, does not seem to have had any problems.) Protestants, on the other hand, especially nonconformists, had much to interest them in the various communities which

had grown up or taken refuge in the Low Countries and Germany. William Caton and others were active there in the 1650s and 1660s, and in 1677 Fox visited Quakers there to encourage and organise them. Catholic Europe also provided the experience of journeying, moderately safely, to observe the practice of an alien religion, given,

as Moryson points out, the proper precautions: ‘There is great art for a Traueller to conceale his Religion in Italy and Spaine, with due wisdome and without offending his conscience’.

18 It even produced spy stories: Anthony Munday (?1560-1633), writer, dramatist, and pageant-master, claimed in The English Romayn Life (1582) to have infiltrated

the newly-founded English College at Rome, where Jesuits were being prepared for the mission to reconvert England:19 though he had taken the precaution of contacting

Cardinal Allen first. (Coryat, on the other hand, does not seem to have had any problems.) Protestants, on the other hand, especially nonconformists, had much to interest them in the various communities which

had grown up or taken refuge in the Low Countries and Germany. William Caton and others were active there in the 1650s and 1660s, and in 1677 Fox visited Quakers there to encourage and organise them.

Journeying at Home

There was a growing literature of stay-at-home tourism to add to the avidly consumed accounts of foreign and exotic places. Some was probably intended to counteract the emphasis

on the attractions of foreign travel: Fynes Moryson speaks of people ‘who not vniustly seeme to feare, lest young men by this course should be peruerted from true Religion, and by this feare,

disswade passing into forraigne parts, as the chiefe cause of this mischiefe’.20 There was also the fear that young men (it is always young men)

returning from their travels might be irretrievably corrupted and, dare one say, feminised by their adoption of foreign dress and manners. There was a growing literature of stay-at-home tourism to add to the avidly consumed accounts of foreign and exotic places. Some was probably intended to counteract the emphasis

on the attractions of foreign travel: Fynes Moryson speaks of people ‘who not vniustly seeme to feare, lest young men by this course should be peruerted from true Religion, and by this feare,

disswade passing into forraigne parts, as the chiefe cause of this mischiefe’.20 There was also the fear that young men (it is always young men)

returning from their travels might be irretrievably corrupted and, dare one say, feminised by their adoption of foreign dress and manners.

To travel at home was more patriotic, and equally rich in interest. Earlier writings concentrate on Britain’s history, especially Roman history, and topographical wonders. Later writers,

like Fiennes and Defoe, are more interested in its growing prosperity and technological development.

At the beginning of the 17th century there was also a craze for travel challenges, their equivalent of our sponsored walks, save that the object of their charity was themselves: Will Kempe morris-danced from London to Norwich in nine days (spread out)

in 1600;21 in 1618, Ben Jonson walked in what became almost a royal progress from London to Edinburgh.

22

Travel at home might also be cheaper and more comfortable: Fynes Moryson, while concentrating on his continental travels, compares

English provision for travellers with them very favourably.

Journeying for Research

The earliest and most productive writers about travel in England (and after the accession of James I and VI, Scotland) were scholars.

John Leland (?1503-1552) was commissioned by Henry VIII

in 1553/1534 to undertake a nationwide search of monastic and other libraries to prevent books

being lost as a result of the Dissolution (by requisitioning them for the royal library). As a result of his travels, and reading descriptions of Britain in the manuscripts he catalogued, he was ‘totally enflammid

with a love to see thoroughly al those partes of this your opulente and ample reaulme, that I had redde of yn the aforesaid writers’, spent six years on this, ‘and notid yn so doing a hole worlde of thinges

very memorable’, which he intended to include in a definitive description ‘of your reaulme yn writing’. He planned to do this county by county, setting the pattern for all future scholarship in the field.

Unfortunately in 1547 he ‘fell beside his wits’, and died three years later, without having completed his great work, but leaving a mass of travel notes, published later as

‘Leland’s

Itinerary’.23 The earliest and most productive writers about travel in England (and after the accession of James I and VI, Scotland) were scholars.

John Leland (?1503-1552) was commissioned by Henry VIII

in 1553/1534 to undertake a nationwide search of monastic and other libraries to prevent books

being lost as a result of the Dissolution (by requisitioning them for the royal library). As a result of his travels, and reading descriptions of Britain in the manuscripts he catalogued, he was ‘totally enflammid

with a love to see thoroughly al those partes of this your opulente and ample reaulme, that I had redde of yn the aforesaid writers’, spent six years on this, ‘and notid yn so doing a hole worlde of thinges

very memorable’, which he intended to include in a definitive description ‘of your reaulme yn writing’. He planned to do this county by county, setting the pattern for all future scholarship in the field.

Unfortunately in 1547 he ‘fell beside his wits’, and died three years later, without having completed his great work, but leaving a mass of travel notes, published later as

‘Leland’s

Itinerary’.23

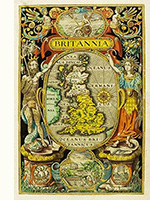

Inspired by his example, and making use of his material, which circulated in manuscript, 16th- and 17th-century antiquaries embarked on a series of comprehensive surveys of the topography of their own country. This was usually accompanied

by a study of its history featuring the material evidences of the past, especially the Roman past, waiting to be turned up in its landscape. William Camden’s

Britannia is the archetype. Writers tended to concentrate on the material with which they could make themselves most familiar, which led, as Leland had planned, to the writing of county histories —

the Victoria County History is only the latest of these massive projects. Some, like Dugdale’s

Antiquities of Warwickshire (1656),24 achieved publication: others, like Christopher Towneley’s projected

History of Lancashire25 and the Rev. Thomas Machell’s Notes on the Barony of Kendal,

26 were swamped by material, and in Machell’s case, the expense of publication.

In order to collect and often sketch their material, especially the evidences of Roman remains, they had to travel, and keep notes. These, published or unpublished, become a branch of travel literature in its own right.

Meanwhile, the published works, especially Camden, become guidebooks for later antiquaries: Ralph Thoresby regrets that for his 1682 journey to Chester he was ‘not so well furnished as I should,

having consulted neither Camden nor Fuller’.27 Inspired by his example, and making use of his material, which circulated in manuscript, 16th- and 17th-century antiquaries embarked on a series of comprehensive surveys of the topography of their own country. This was usually accompanied

by a study of its history featuring the material evidences of the past, especially the Roman past, waiting to be turned up in its landscape. William Camden’s

Britannia is the archetype. Writers tended to concentrate on the material with which they could make themselves most familiar, which led, as Leland had planned, to the writing of county histories —

the Victoria County History is only the latest of these massive projects. Some, like Dugdale’s

Antiquities of Warwickshire (1656),24 achieved publication: others, like Christopher Towneley’s projected

History of Lancashire25 and the Rev. Thomas Machell’s Notes on the Barony of Kendal,

26 were swamped by material, and in Machell’s case, the expense of publication.

In order to collect and often sketch their material, especially the evidences of Roman remains, they had to travel, and keep notes. These, published or unpublished, become a branch of travel literature in its own right.

Meanwhile, the published works, especially Camden, become guidebooks for later antiquaries: Ralph Thoresby regrets that for his 1682 journey to Chester he was ‘not so well furnished as I should,

having consulted neither Camden nor Fuller’.27

Journeying for Pleasure, Health, Instruction, and a Bet

Even when roads were bad and the journey potentially hazardous, intrepid travellers like

Celia Fiennes (1662-1741) seem to have been

addicted to travel for its own sake, though her presented reason is ‘to regain my health by variety and change of aire and exercise’, and she writes knowledgeably about spas. An earlier member of the family

which produced the explorer Sir Ranulph Fiennes, she covered a large part of the country on horseback, embarking on her ‘Great Journey’ to the North in 1697/8.

For a change, she was not interested in antiquities, but fascinated by the practicalities of everyday living in different parts of the kingdom: the houses they lived in, what they ate (and offered to travellers),

and what they

did for a living — she is particularly interested in manufacturing processes. She also remarks on road conditions, and approves the newly-invented signposts to be found in Lancashire at each crossroad,

‘with the names of the great town or market towns that it leads to ... that strangers may not lose their road and have to goe back againe.28 Even when roads were bad and the journey potentially hazardous, intrepid travellers like

Celia Fiennes (1662-1741) seem to have been

addicted to travel for its own sake, though her presented reason is ‘to regain my health by variety and change of aire and exercise’, and she writes knowledgeably about spas. An earlier member of the family

which produced the explorer Sir Ranulph Fiennes, she covered a large part of the country on horseback, embarking on her ‘Great Journey’ to the North in 1697/8.

For a change, she was not interested in antiquities, but fascinated by the practicalities of everyday living in different parts of the kingdom: the houses they lived in, what they ate (and offered to travellers),

and what they

did for a living — she is particularly interested in manufacturing processes. She also remarks on road conditions, and approves the newly-invented signposts to be found in Lancashire at each crossroad,

‘with the names of the great town or market towns that it leads to ... that strangers may not lose their road and have to goe back againe.28

There is also a whole outcrop of comic (though genuine) ‘travels’, resolutely not undertaken for edification, and

often as the result of a bet. They were probably kick-started by Will Kempe’s Nine Days’ Wonder (1600),29

the account of the comedian’s marathon morris dance from London to Norwich. John Taylor, the ‘Water Poet’ (he was a Thames Bargeman) wagered that he could travel from London to Edinburgh

(and a fair way round Scotland), paying nothing for accommodation on the way; his adventures are chronicled in The Pennyless Pilgrimage (1618).

He either stayed with patrons, or got them to pay his inn bills: in return he celebrated them in verse. He explains the quid pro quo: He either stayed with patrons, or got them to pay his inn bills: in return he celebrated them in verse. He explains the quid pro quo:

I was kind Mr. Barnards costly Guest:

To me he shew'd his bounty from the Mint,

For which I give him heer my thanks in Print.

He payd the chinque [chink, ‘cash’], and freely gave me drink,

And I returne my gratitude with Ink.30.

Taylor (and incidentally Ben Jonson) gives some idea of the context of hospitality round Fox’s journeys. The runaway success in the genre belonged to

Richard Brathwaite’s (1588-1673) Drunken Barnaby (1638), a cheerful Latin poem with a doggerel English translation purporting to be the travels of a dedicated drunkard

on an extended pub crawl which leaves no inn unvisited or barmaid unmolested between London and Sedbergh.31 His description of the inns and

their obliging landladies carries an unnerving conviction. Since Brathwaite was a native of Kendal, he incidentally provides a detailed itinerary which is helpful for the earlier part of Fox’s travels.

Journeying for Work and Education

Travel was part of everyday life. Judges like Thomas Fell rode on circuit. JPs attended the Assizes. So, obviously, did the accused:

Francis Howgill was arrested at Kendal and sent to appear at Appleby. Bishops and heralds made official Visitations. The gentry, who were incurably litigious, had to go to London for appearances before the courts

of the Duchy of Lancaster or Star Chamber, or to answer for misdemeanours before the Ecclesiastical Commission at York. In 1660 Margaret Fell rode to London to speak to the King in person on Friends’ sufferings,

and presented him with a written statement about their stance on peace. Students went to school in Kendal or Sedbergh or St Bees and then if they were successful on to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

Young gentlemen went to the Inns of Court. (The Catholics sent their offspring even further, though illegally, to Douai and St Omer and the University of Leuven.) Armies marched through with their baggage trains

to repel invasion, and sent reports back to HQ. There was frequent coming and going from Ireland. Travel was part of everyday life. Judges like Thomas Fell rode on circuit. JPs attended the Assizes. So, obviously, did the accused:

Francis Howgill was arrested at Kendal and sent to appear at Appleby. Bishops and heralds made official Visitations. The gentry, who were incurably litigious, had to go to London for appearances before the courts

of the Duchy of Lancaster or Star Chamber, or to answer for misdemeanours before the Ecclesiastical Commission at York. In 1660 Margaret Fell rode to London to speak to the King in person on Friends’ sufferings,

and presented him with a written statement about their stance on peace. Students went to school in Kendal or Sedbergh or St Bees and then if they were successful on to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

Young gentlemen went to the Inns of Court. (The Catholics sent their offspring even further, though illegally, to Douai and St Omer and the University of Leuven.) Armies marched through with their baggage trains

to repel invasion, and sent reports back to HQ. There was frequent coming and going from Ireland.

Commerce depended on travel. The earliest road maps show markets, and market days. Then as now, haulage was an essential industry. Scheduled carriers plied up and down the country with parcels of goods

ordered from London and other commercial centres, and with letters.

Cattle drovers herded their animals hundreds of miles down age-old routes.

Horses were bought and sold at horse fairs. Those who could afford it

made shopping trips to London, visited their publishers, and enlarged their acquaintance. They recorded their expenses, and occasionally itineraries, in the blank pages of printed almanacs, designed and sold

for the purpose. Household servants made journeys on their masters’ behalf. Friends and families visited each other. A great lady like Anne Clifford had several homes and commuted between them

with her household, almost in the style of a royal progress.32 She had resolved never to return to the South again, but records with great pleasure and pride

the visits of her grandchildren and greatgrandchildren. The businessman Ralph Thoresby rode from Leeds

to the Cumbrian Coast to check out a proposed marriage for his sister-in-law — he was not impressed by the suitor’s financial circumstances, and the marriage did not

take place.33 Any image of England as a stay-at-home society with no horizons beyond the next village dissolves very rapidly in the face of the evidence. Cattle drovers herded their animals hundreds of miles down age-old routes.

Horses were bought and sold at horse fairs. Those who could afford it

made shopping trips to London, visited their publishers, and enlarged their acquaintance. They recorded their expenses, and occasionally itineraries, in the blank pages of printed almanacs, designed and sold

for the purpose. Household servants made journeys on their masters’ behalf. Friends and families visited each other. A great lady like Anne Clifford had several homes and commuted between them

with her household, almost in the style of a royal progress.32 She had resolved never to return to the South again, but records with great pleasure and pride

the visits of her grandchildren and greatgrandchildren. The businessman Ralph Thoresby rode from Leeds

to the Cumbrian Coast to check out a proposed marriage for his sister-in-law — he was not impressed by the suitor’s financial circumstances, and the marriage did not

take place.33 Any image of England as a stay-at-home society with no horizons beyond the next village dissolves very rapidly in the face of the evidence.

On the practical side of travel writing, road maps, starting with John Ogilby, were marketed as aids to one’s journey, and often, as well as distances

(and warnings on which roads not to take), provided information about the state of the road, the likelihood of acquiring refreshments or a lodging along the way, and occasionally points of interest:

Westmorland and Cumberland

... [of the road from Egremont to Carlisle] the Thurle [?Ehen], Darwen [Derwent], Coker [Cocker], Eln [Ellen], Wampul [Wampool] and Cauda [Caldew] are the chief Rivers crost over; which is in General as bad a Road as any in England, being very Hilly, Stony and Moorish, where you seldom meet

with that Entertainment as in the more Frequented Roads in the Midle of the Kingdom.

... [of the road from Kendal to Egremont] At 95. you pass through Winandermere [Windermere] a little Village, where you descend a Hill call’d St. Kathern’s Brow, and at the bottom over a Stone-bridg cross a Brook, and have Winandermere Water or

Lake accompaning your Road on the Left, which Lake is the biggest in all England, and is plentifully supply’d with Fish; whence crossing a Stone-bridg and Brook, and by a Wood on the Right and some

disperst Houses, are convey’d at 132. to Ambleside of 4 Furlongs Extent and good Accomodation, seated near Winandermere Water, and hath the benefit of a Market on Wednsdays, which is indifferently

well Provided with most Necessaries.34

Britannia Depicta, the pocket-sized version of Ogilby by John Owen and Emmanuel Bowen (1720 and frequently reprinted),

is more tourist-oriented. The margins are filled with historical

descriptions of the major places of interest along the route. By the time of John Cary’s New Itinerary (1798), these have been replaced by an exhaustive list of stately homes and inns,

already trialled in his 1790 London area survey: ‘Every Gentleman's Seat, situate on, or seen from the Road, (however distant) are laid down, with the Name of the Possessor;

to which is added The Number of INNS on each separate Route’.35 This clearly facilitated the kind of National-Trust-before-the-event visiting

engaged in by Elizabeth Bennet and Mr and Mrs Gardiner in Pride and Prejudice. Parallel to this — ‘what are men to rocks and mountains?’ — Thomas West’s 1778

Guide to the Lakes is credited with kickstarting the passion for Lake District tourism and its search for the

picturesque.36 Britannia Depicta, the pocket-sized version of Ogilby by John Owen and Emmanuel Bowen (1720 and frequently reprinted),

is more tourist-oriented. The margins are filled with historical

descriptions of the major places of interest along the route. By the time of John Cary’s New Itinerary (1798), these have been replaced by an exhaustive list of stately homes and inns,

already trialled in his 1790 London area survey: ‘Every Gentleman's Seat, situate on, or seen from the Road, (however distant) are laid down, with the Name of the Possessor;

to which is added The Number of INNS on each separate Route’.35 This clearly facilitated the kind of National-Trust-before-the-event visiting

engaged in by Elizabeth Bennet and Mr and Mrs Gardiner in Pride and Prejudice. Parallel to this — ‘what are men to rocks and mountains?’ — Thomas West’s 1778

Guide to the Lakes is credited with kickstarting the passion for Lake District tourism and its search for the

picturesque.36

Perhaps after skimming through all these writers, one can see one way in which Fox fits into the genre. The idea of a journey as a period of self-abnegation does not seem to have been a feature of

British travel-writing. They are all out to collect something, even if it is not a carriage-load of artworks from the Grand Tour. At its most basic, it can just be a list of places visited.

But most writers have a further aim. Camden collects historical data; Celia Fiennes collects interesting

information; Drunken Barnaby collects landladies and pints; they all collect experiences. Fox collects convincements and Sufferings. Each of these provides a sense of achievement and self-vindication.

Links to Biographies and Excerpts from Travellers in the North West

John Leland (?1503-1552) MS Itinerary

William Camden (1551-1623) Britannia (1586)

Fynes Moryson (1566-1630) Itinerary (1617)

John Taylor (1580-1653) The Pennyless Pilgrimage (1618)

Richard Brathwaite (1588-1673) Drunken Barnaby (1638)

Lady Anne Clifford (1590-1676) MS Diaries

John Ogilby (1600-1676) Britannia (1675)

Rev. Thomas Machell (1647-1698) MS Collections (published 1963)

Celia Fiennes (1662-1741) MS Journal (published 1888)

Ralph Thoresby (1658-1725) MS Journal (published 1830)

Daniel Defoe (c.1660-1731) A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain (1724–1727)

Where possible, links are provided to the texts mentioned in the footnotes

1. The Itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535-1543 edited Lucy Toulmin Smith, 5 vols

(London: George Bell and Sons, 1909) 4 (Parts VII and VIII) page 11. Return

2. The embassy from Charles X Gustaf of Sweden to Sultan Mehmet IV of Turkey in 1657. The ambassador was Claes Rålamb. For more information, see

Jonathan Stubbs

‘The Rålamb Mission’ Aramco World 64:2 (March/April 2013). Return

3. A useful survey is The Cambridge History of Travel Writing edited Nandini Das and Tim Youngs (Cambridge UP, 2019), also online

for subscribers at

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316556740. Interestingly, it concentrates on the experience of the traveller abroad, not in one’s native country, which is the focus of this piece.

Return

4. On ‘Mandeville’ (pseudonym), see the Wikipedia entry.

For a handy translation, see The Travels of Sir John Mandeville translated Charles Moseley (Penguin Classics; London: Penguin, 1983, new edition 2005); or Mandeville The Book of Marvels and Travels

translated Anthony Bale (World's Classics; Oxford University Press, 2012). For some manuscript illustrations, see

British Library Harley MS 3854, especially the pilgrimage section from fol.1r–fol.24r (scroll down on right). The textual history of Mandeville is extremely complex, and

there are many editions of individual manuscripts. Return

5. The Itineraries of William Wey edited and translated Francis Davey (Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2010). Return

6. Petrarch’s Guide to the Holy Land edited and translated Theodore J. Cachey Jr (University of Notre Dame Press, 2002).

Return

7. ‘This have I herde of marchaundis relacions’ from The Libelle of Englyshe Polycye: A Poem on the Use of Sea-Power, 1436 edited G. Warner (Oxford, 1926),

line 533. Return

8. ‘Nel nome di Dio e del guadagno’: the motto of the italian merchant Francesco di Marco Datini of Florence (c.1335-1410); Iris Origo

The Merchant of Prato Return

9. The most remarkable portolan chart, though made for presentation to Charles V of France, and halfway between a chart and an artwork, is the

Catalan Atlas of 1371 by the Majorcan cartographer Abraham Cresques (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des Manuscrits, Espagnol 30).

The Wikipedia entry

shows the pages arranged as a continuous sequence. The first four pages are extremely accurate; after that they enter the realms of legend.The West Coast of Africa is very accurately depicted, together

with an image of the galley of the Majorcan Jaume Ferrer, whose expedition to find the legendary ‘River of Gold’ disappeared without trace in 1346.

It is suggested that the decorated charts that survive were also meant for display and not for use in sea-going conditions. For further examples, see the

National Maritime Museum’ blog. Wikipedia’s image bank is remarkably comprehensive. Return

10. Thomas Coryat Coryat’s Crudities, Hastily gobled vp in five Moneths trauells (London: W[illiam] S[tansby], 1611), online at

archive.org;

Thomas Coriate Traveller for the English Wits (London: W. Jaggard and Henry Featherstone, 1616), online at archive.org;

the title page shows him astride an elephant. On distance, page 19; encounter with the Sherleys, pages 14-17; arrival of Rowe/Roe, page 35. For Rowe’s diary of his embassy, see The Embassy of

Sir Thomas Roe to India 1615-1619 edited William Foster, 2 vols Hakluyt Society 2nd series 1 & 2 (1899), online at archive.org (Vol.1) and

archive.org (Vol.2)

Return

11. Richard Hakluyt Divers Voyages Touching upon the Discoverie of America (London: Thomas Woodcocke, 1582); Principall Navigations, Voiages

and Discoveries of the English Nation (London: George Bishop and Ralph Newberie, 1589); The Principal Navigations, Voiages, Traffiques and Discoueries of the English Nation 3 vols

(London: George Bishop, Ralph Newberie, & Robert Barker, 1599-1600). Return

12. Richard Hakluyt A Particuler Discourse Concerninge the Greate Necessitie and Manifolde Commodyties That Are Like to Growe to This Realme of Englande

by the Westerne Discoueries Lately Attempted, Written in the Yere 1584: manuscript: published as A Discourse on Western Planting edited Charles Deane (Cambridge, Mass: John Wilson & Son, 1877), online at

archive.org.

Return

13. Hakluyt Discourse page 3. Return

14. Samuel Purchas Hakluytus posthumus or Purchas his pilgrimes (London: Henry Fetherstone, 1624). Return

15. William Bradford History ‘Of Plimouth Plantation’ from the original manuscript (Boston, Mass: Wright & Potter (printers)

for Massachusetts General Court, 1898) pages 32-3, 72. Online at archive.org.

Return

16. Coryat Traveller pages 14-17. Return

17. Fynes Moryson An itinerary written by Fynes Moryson Gent. First in the Latine tongue, and then translated by him into English ... (London:

John Beale, 1617) Part 3 Book 1 chapter 1. Transcription online at Early English Books Online

Text Creation Partnership (page 8 in this section). Return

18. Moryson Itinerary Part 3 Book 1 chapter 2; EEBO TCP

(page 30 in this section). Also ‘The inquiring after the secrets of Religion, and desiring to bee present at those Rites, hath made many perish’; Part 3 Book 1 chapter 2 (page 25).

Return

19. Anthony Munday The English Romayne lyfe. Discouering: the liues of the Englishmen at Roome ... (London: John Charlewoode for Nicholas Ling, 1582)

transcription by EEBO TCP.

Return

20. Moryson Itinerary Part 3 Book 1 chapter 1; EEBO TCP

(page 7 in this section). Return

21. Will Kempe Kemps nine daies wonder. Performed in a daunce from London to Norwich (London: Nicholas Ling, 1600);

transcription by EEBO TCP.

Return

22. See

Ben Jonson’s Walk, CEngage blog, University of Edinburgh. Jonson never published an account of his journey; this project was sparked by the discovery of a manuscript account by Johnson’s

travelling companion, now published as Ben Jonson's Walk to Scotland: An Annotated Edition of the ‘Foot Voyage’ edited James Loxley, Anna Groundwater, and Julie Sanders (Cambridge UP, 2014).

Return

23. John Leland The itinerary of John Leland in or about the years 1535-1543. Parts I to III (London: George Bell & Sons, 1907) pages xxxvii-xliii

‘Leland’s New Year’s Gift’, report to Henry VIII, at archive.org;

Parts VII and VIII edited Lucy Toulmin Smith (London: George Bell & Sons, 1909) pages 5-11, Preston to Kendal, at archive.org;

Parts IX, X, and XI edited Lucy Toulmin Smith (London: George Bell & Sons, 1910) pages 44-8, Lancashire and Westmorland; pages 50-56, Westmorland and Cumberland; pages 146-7, more on Westmorland; at

archive.org and later pages.

See also John Leland for biography and transcriptions.

Return

24. William Dugdale The Antiquities of Warwickshire (London: printed by Thomas VVarren, 1656): online at

archive.org. Return

25. The best account of Christopher Towneley is by Frances Wilmott in

the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB), but this requires a subscription to access. His antiquarian papers are scattered through most major libraries, and

continue to be one of the most important sources for the history and genealogy of Lancashire. Return

26. Thomas Machell Antiquary on Horseback: The Collections of the Rev. Thos. Machell Chaplain to King Charles II Towards a History

of the Barony of Kendal edited Jane M. Ewbank Cumbria and Westmorland Archaeological and Antiquarian Society Extra Series 19 (1963). The manuscripts are in the Carlisle

Record Office, and are © The Dean and Chapter of Carlisle Cathedral. Return

27. Ralph Thoresby The Diary of Ralph Thoresby edited Joseph Hunter (London: Colburn and Bentley, 1830) page 120. Return

28. The Journeys of Celia Fiennes edited Christopher Morris (London: The Cresset Press, 1949) 190, 192. She is worried about her horses, ‘

for these stony hills and wayes pulls off a shooe presently [almost at once] and wears them as thinn that it was a constant charge to shooe my horses every 2 or 3 days’, though fortunately

somewhere near Ambleside she manages to find a very good smith, who ‘did shooe them so well and so good shooes that they held some of the shooes 6 weeks; the stonyness of the wayes all here about

teaches them the art off makeing good shooes and setting them on fast’ (page 197). Return

29. Will Kempe Kemps nine daies wonder. Performed in a daunce from London to Norwich (London: Nicholas Ling, 1600);

transcription by EEBO TCP.

Return

30. John Taylor The Pennyles Pilgrimage, or the Money-lesse Perambulation (London: Edward Allde, 1618).

transcription by EEBO TCP.

He went up via the North West through Lancaster and Kendal. In Edinburgh he wandered the streets, looking for someone with whom he could claim acquaintance; eventually he fixed a likely person with a very hard stare.

He arrived at the same time as his acquaintance Ben Jonson, who had walked the whole way up the East Coast route. Taylor got into print, while Jonson did not.

The quotation is from his The certain travailes of an uncertain journey begun on Tuesday the 9. of August, and ended on Saturday the 3. of September following, 1653 (London: no publisher, 1654),

transcription by EEBO TCP.

when he was 74; he maintains that he is forced to earn his living this way, especially since the King and his court can no longer be his patrons. He died later that year.

Return

31. Richard Brathwaite Barnabees journall under the names of Mirtilus & Faustulus shadowed: for the travellers solace lately published, to most apt numbers reduced,

and to the old tune of Barnabe commonly chanted. By Corymbœus or Barnabae itinerarium (London: John Haviland, 1638); transcription by EEBO TCP.

Despite the adoption of the persona, Brathwaite was an Oxford graduate, and the original was written in Latin in imitation of an eclogue. The doggerel translation was to be sung to a popular tune which so far has escaped

identification, though Ben Jonson apparently refers to it as ‘Whoop Barnaby’. In another version of the academic pub-crawl, Richard Corbett’s Iter Boreale (‘Journey to the North’) in

Certain elegant poems, written by Dr. Corbet, Bishop of Norvvich (London: Andrew Crooke, 1647) pages 1-17, the (postgraduate) students unfortunately do not get any further north than Newark on Trent

because they run out of funds. Return

32. The Diaries of Lady Anne Clifford edited D.J.H. Clifford (Stroud: Sutton, 1990; pb Cheltenham: History Press, 2009 and reprints).

Return

33. For the journey, see Ralph Thoresby ‘Journey to Cumbria 1694’.

Also Letters addressed to Ralph Thoresby edited W.T. Lancaster (Leeds: Thoresby Society, 1912) page 35: Letter from the Rev. Richard Frankland. Return

34. John Ogilby Britannia, Volume the First: or, An Illustration of the Kingdom of England and Dominion of Wales: By a Geographical and Historical Description

of the Principal Roads thereof (London: Ogilby, 1675) page 191. Return

35. John Cary Cary’s New Itinerary: Or, An Accurate Delineation of the Great Roads, Both Direct and Cross, Throughout England and Wales (London: J. Cary, 1798);

Cary’s Survey of the High Roads from London (London: J. Cary, [1790]) title page. Return

36. First edition Thomas West Guide to the Lakes (London: Richardson and Urquhart; Kendal: Pennington, 1778). The history of its illustrations is complex.

The fourth edition (1789) advertises 20 engravings, which had been heralded in the third edition. Return

|