How to use ensembles of climate models

Posted on

This summer you may have seen the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, which synthesised the most up to date understanding of the climate. Its key findings include (1) that doubling CO2 compared to pre-industrial levels would produce approximately 3 degrees of warming, and (2) that it is virtually certain that extreme heat events have become more common and more intense since the 1950s.

Many of these findings rely on using climate models to investigate and predict the long-term behaviour of Earth’s surface and atmosphere. These computer models encode the physics and chemistry of the Earth’s climate system and provide researchers with a lab-like environment to conduct experiments. This allows them to explore how parts of the Earth will evolve and change, particularly under human influences.

Results within the IPCC report often rely on information from more than one climate model. This effectively gives us repeated experiments and can boost our confidence in a projection if all the models simulate similar outcomes.

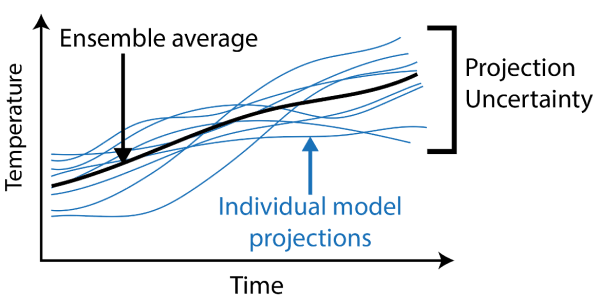

This method of using a collection of comparable model simulations is known as an ensemble. The models within an ensemble, though comparable, are different and therefore produce a range of projections. The models might produce simulations for a selection of model parameters (so-called perturbed physics ensembles), or they might simulate a world where Net Zero is reached sooner depending on the experimental setup. As well as these controlled differences, models will be different because of the way they have been designed. These models are often millions of lines of code long, so there are many reasons for two independently designed models to be different! (See here for a nice graphic of what a million lines of code looks like).

With all these model simulations within an ensemble, the question is how do we combine them into one single projection of the future?

When combining models there are a number of things to consider. Firstly, all models are not equally good at simulating all aspects of the climate system. This is unsurprising given the complexity of the models and the system they simulate. For example, some models better simulate certain regions , while others better capture extreme heat events. Secondly, different models can be very similar. If two models are very similar (I.e. they simulate the ocean using the same sub-model) then our sample of models is undesirably biased and not independent.

With that in mind, how do we use this information to produce better projections rather than simply averaging across all the models? Tackling this question was the focus of my PhD and will be central to my research as part of the DSNE project. Below I briefly outline two ways that we have been looking at doing this.

Weighting models

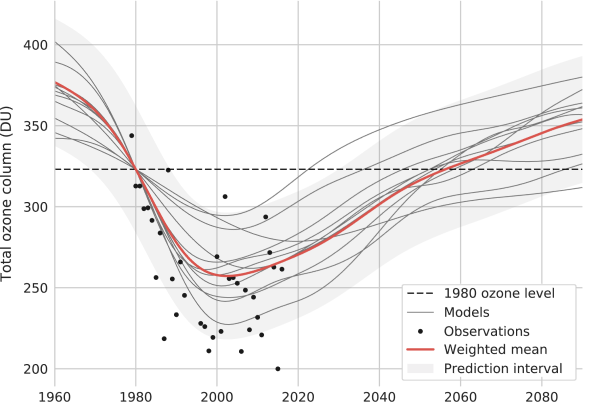

One approach is to quantify how good a model is through a comparison of the model to observations and weight it accordingly. A model that is good at recreating past observations gets highly weighted. This model therefore contributes more to the ensemble projection than a less skillful model.

We have used this weighting method to provide up-to-date estimates of ozone hole recovery – approximately mid 2050s on our current trajectory. As well as quantifying how well models simulate ozone, we also included how well models simulate the broader processes that affect the formation of the ozone hole. This ensures that models are highly weighted only if they simulate the whole ozone system well.

A Bayesian neural network

Another way that we've been considering model ensembles is by using machine learning to create more accurate ensemble predictions and projections. The tool we use for this is a Bayesian neural network (see this interactive demo), which learns how to optimally combine models to recreate observations. In doing this we account for models which might be more skillful in certain regions or season.

A key application of our Bayesian neural network is filling in gaps in historic observation records. As we’ve learnt how to recreate observations using model simulations, we can estimate what the observation might have been in regions and times for which no observations exist. To this end we’ve produced continuous records of historic ozone in the atmosphere.

The way forward

Climate model simulations are important, and they provide an essential window into the future. Just recently two pioneers of climate modelling were awarded a Nobel prize which acknowledges how important these models are. Although the models are well tested, they are imperfect because they cannot precisely simulate a system so enormously complex as the Earth, its atmosphere and inhabitants. It is therefore necessary to keep working on methods, drawing on statistics and machine learning, to make better use of climate models to provide projections of the future climate.

Related Blogs

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.

Back to blog listing