Karen Lloyd Writer in Residence page

'Karen's writing is concerned with the natural environment and the ways humans are entangled with nature.

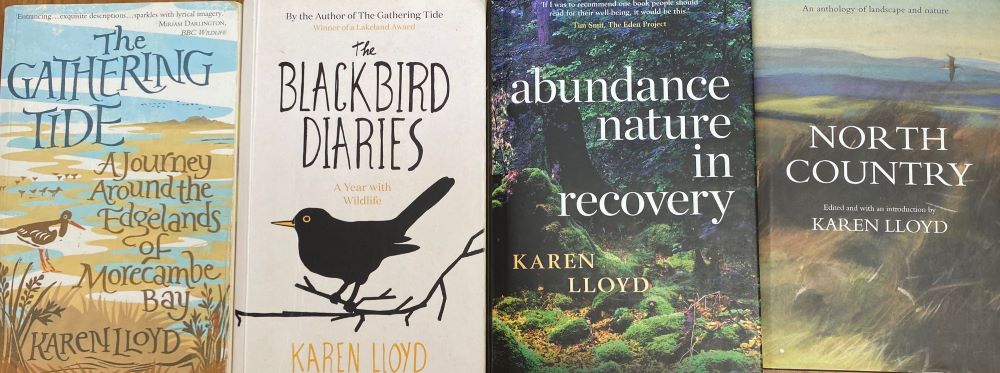

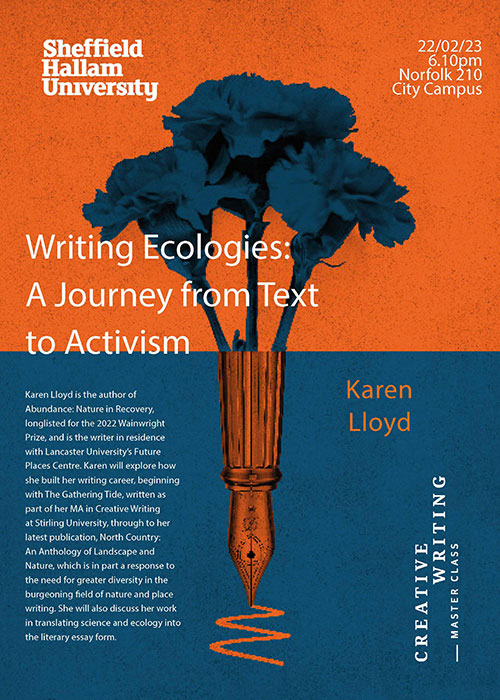

Her work is widely published including the James Cropper Wainwright Prize 2022 longlisted Abundance: Nature in Recovery, (Bloomsbury, 2021) and The Gathering Tide: A Journey Around the Edgelands of Morecambe Bay (Saraband, 2015).

She is the editor of North Country: An Anthropology of Landscape and Nature (Saraband, 2022) and co-editor of The Wolf: Culture, Nature and Heritage (Boydell and Brewer, 2023).

Her essays are published on Lit Hub (Kinds of Blue: On the Human Need to Swim) and 'Inside the Rockpool Shrimp there is a Dying Star', in An Anthology of Speculative Nature, (Pegasus, 2023).

Karen is part of Paperboats, a collective of writers whose work focuses on nature and environment. Although based in Scotland (begun as an initiative from Stirling University Department of Creative Writing) Paperboats is global in outlook, with writers engaging with the astonishing life which exists on this planet. Find out more about Paperboats.