Successful PhD student Dr Lucy Magoolagan explains why her research, on the song of Britain’s only aquatic songbird, captured the imagination of the producers of the BBC Springwatch programme

Fieldwork can be intensive. During my PhD, whatever the weather, you’d find me on the riverbank for six months of the year, searching for dippers.

The song of these fascinating little birds, named for their bobbing behaviour, were the subject of my PhD, which I’ve just completed at Lancaster University.

In January, I began to record song when aggression between individuals is particularly high. Pairs defend territories and mates from intruders, and single males sing to attract a female before the breeding season starts.

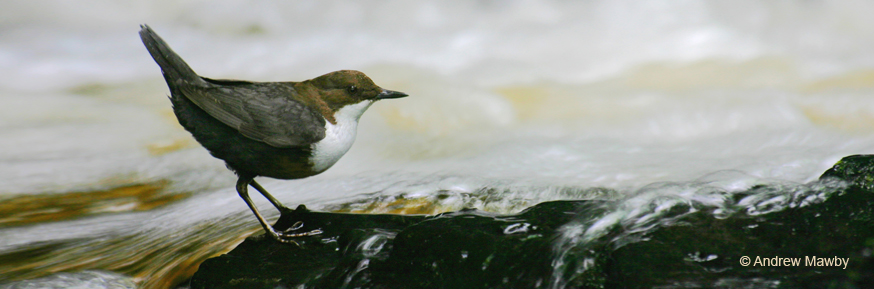

Dippers are an indicator species for river quality, as their diets consist of aquatic macro-invertebrates and small fish. They forage for these prey items by diving into the water and seemingly walking along the bottom of the river using their strong toes and wings to keep them submerged.

My PhD was part of a long term research project into how environmental change affects the behaviour and ecology of dippers, using a population of the species which have been monitored since the 1950s.

Researching on the river bank

This population lives within a 4-mile radius of Sedbergh, in Cumbria; around 35 minutes north of the Lancaster Environment Centre, where I’m based. This area provides a wide range of habitats for dippers, as four rivers converge.

The team - consisting of my supervisor, Dr Stuart Sharp, and myself, along with one or two Masters students and a few volunteers - collect breeding, ecological and behavioural data from around 40-50 pairs each year.

The first few pairs begin to build nests together at the end of February. Nests are checked regularly once completed to ensure we get the date of the first egg for each pair, and from this we can calculate when they will hatch.

Once the chicks have hatched we observe feeding rates of the parents, and place colour rings on the chicks when they reach nine days old. The whole population is colour ringed with a unique combination for each bird, enabling us to monitor them at a distance, and to relate an individual’s life history to its song.

What’s in a song

My PhD focused firstly on a descriptive analysis of the song; something that had not been done before due to the noisy environments in which dippers live.

I analysed the song produced by both sexes and found that both males and females sing complex, highly improvised song. Both sexes use song to defend their territory but, within pairs, it was more common for males to do this.

I also found that males who were unpaired at the start of the breeding season produced more song, that was more complex, than the song produced later in the season by breeding males.

It seems likely that the elaborate song, produced early in the season, is used to attract a mate by advertising the ‘quality’ of a male.

Early environment impacts an individual's adult song characteristics

The next part of my analysis studied chicks that were born within the field site and then became part of the breeding population. I wanted to test out the ‘developmental stress hypothesis’.

This is a theory that stress experienced during early life can impact on an individual adult’s characteristics. The aim was to look at what potential environmental factors could affect the development of song in adults.

We looked at the relationships between an individual’s early life conditions and various adult song characteristics. The results showed that body size, number of siblings, as well as the rate at which food was provided by parents all influenced adult song characteristics.

This was the area of our research that fascinated the BBC’s Springwatch, who interviewed Stuart for the programme.

Further analyses focusing on how these elaborate song characteristics are beneficial in the long-term, revealed that individuals with more complex song had more chicks. We think this is because elaborate song is an ‘honest’ sign of a male’s quality.

This shows the impact the first few weeks of life can have in determining an individual’s future and adds further evidence to support the ‘developmental stress hypothesis’ from a wild bird population.

Ideally, future work would look at whether female song shows the same variation with early life stress and whether song characteristics also affect a female’s reproductive success, something which has only previously been found in the superb fairy-wren.

Watch Dr Stuart Sharp explain the research on this episode of Springwatch. Read Lucy’s PhD blog to learn more about her research and what it’s like doing a PhD. Find out about funded PhD opportunities at our Graduate School for the Environment.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed by our bloggers and those providing comments are personal, and may not necessarily reflect the opinions of Lancaster University. Responsibility for the accuracy of any of the information contained within blog posts belongs to the blogger.