Destabilizing Frames: A Conversation with Joey Holder

Following the first Unsecurities Lab workshop at Lancaster University, artist Joey Holder discusses her approach to disruption, collaborative world-building, and the ethical double standards between art and science.

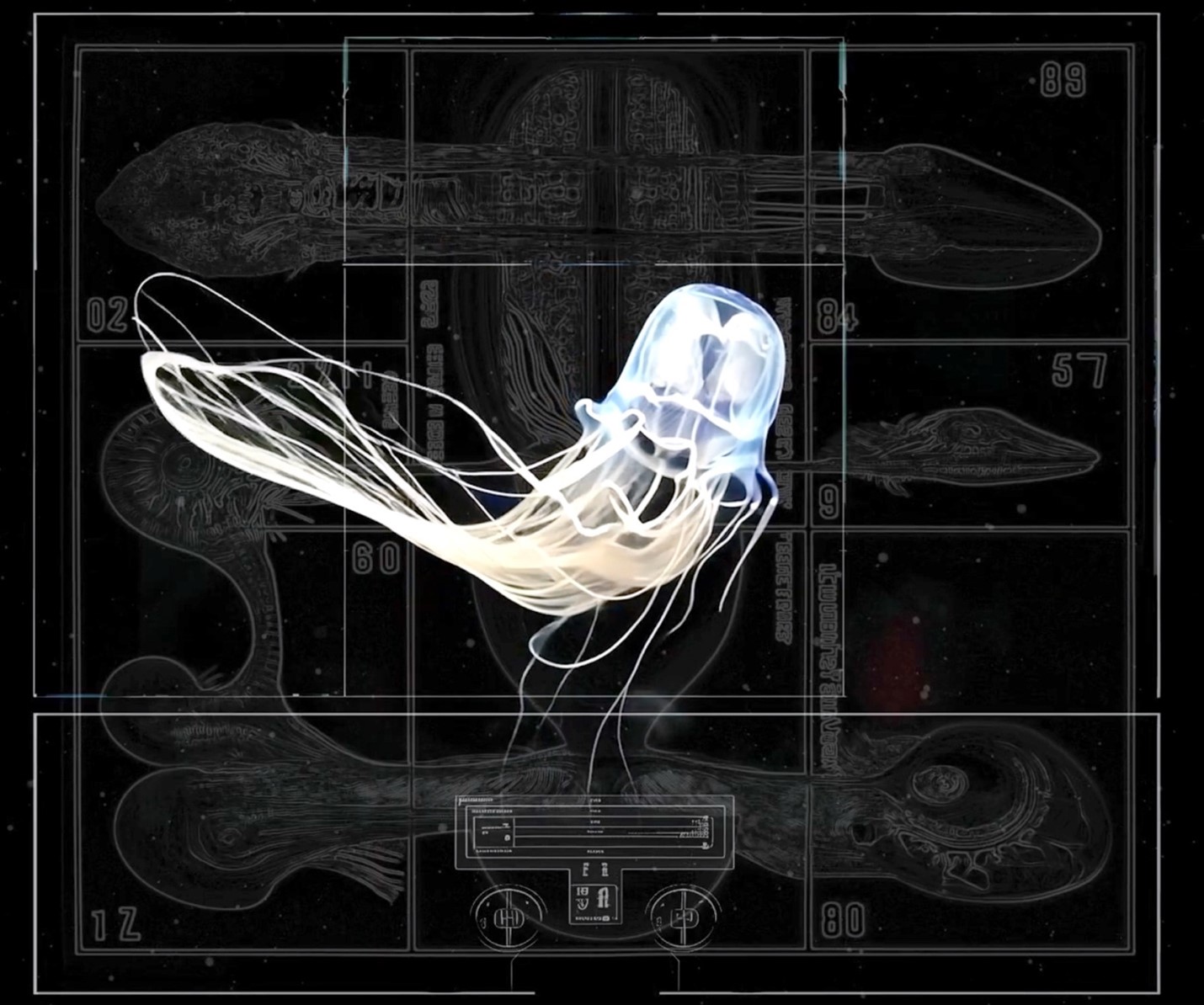

Joey Holder is a UK-based visual artist whose work explores expanded ecologies, synthetic life, and distributed intelligence. Using CGI, scientific imaging, and speculative fiction, she creates immersive video installations that simulate posthuman and algorithmic environments. Holder collaborates with scientists and researchers to probe the limits of systems-based thinking, drawing connections between biological, technological, and planetary processes.

Your work was shown – and analysed – as a "security incident" in a non-gallery space. How did that approach feel to you?

I always respond specifically to the space; sites and contexts. Showing it in this space was fitting, because the piece was originally set up to act like a control room environment. It intrigued me that the scenario involved "an incident" followed by a "stable state," which raises questions about entropy and balance, and whether these things exist or are human constructs. My work shows strange deep-sea creatures, embryonic forms and ROV explorations that evolve, crash, adapt, and mutate—systems of emergent complexity rather than moral equilibrium. People seemed confused about what exactly happened, which I think is important. If they clearly identified a specific incident, it wouldn't have achieved the same impact.

People seemed unsettled by the work. Was that intentional?

If it throws people off their usual track, that's productive. I noticed in the transcripts they found it difficult to articulate the work within their own disciplines. We all have these structures within which we view the world, conduct our research and construct meaning. If the artwork makes participants question or destabilize their usual frames of reference, then it's working. Nature doesn't settle—disturbance is normal, but our cultural channels clean it up to be otherwise.

Your creatures are often described as "monstrous." Is that how you see them?

What's described as monstrous is often just the unknown—that's what scares us most. My work aims to highlight that nature is always in flux—it isn't about fixed identities, but differences and possibilities we can never fully understand. Many creatures don't neatly fit into our systematic taxonomies. I want my work to be an uncovering of the unknown, an unclean version, which I think is closer to what the world is actually like. I think it's part of being human—to be comforted by thinking that there is some kind of underlying order, where living systems behave in predictable ways. With regards to the parts breaking off due to the imperfections of the AI processes when creating them, it may seem unsettling, but to me seems closer to life and its fluidity, its slippage, bodies which are porous. Maybe a good metaphor of what I am trying to describe is something like the Instagram account 'mysleezywildlife'. Here you see animals behaving badly, unedited kills, slow death, disease and all the 'horror', which is, after all what life is—nothing has been cleaned up for us here.

In the workshop, experts became active participants in your work. What was that like?

That's exactly where I want the work to go. I don't know how to say it more eloquently, but I want the work to have agency. I want it to have some kind of use value. We're already living in this simulated, gamified reality—so why not test these scenarios with real people inside automated environments and see what emerges? That can teach us something about how to plan for unknown futures. This situation might not work for every artist—some might prefer more control or distance—but for me, having participants in the space, responding and having conversations, that's part of the work. Their dialogue adds another layer to it. This setting might just be the start of building the ‘world’. What happens next—what's built on top of that—is the real substance.

Some participants weren't sure if they were part of the artwork...

Yes, I think they became part of the material of the work. In the second piece, there was a marine security expert and a neuroscientist. We asked them to act as ambassadors from the collective consciousness of one of the immortal creatures. They fully inhabited the role, even adjusted their vocabulary. That's real immersion—not through visuals, but through complete cognitive involvement.

Tell us about your PhD research on "open worlding."

There's a lot of current discussion in the art world around 'world-building', especially because of game engine technology—people are building virtual worlds, with characters, environments, scenarios. We're also living in this gamified reality in many ways—politics, our daily life—so I'm not interested in creating a digital double of reality or building a self-contained world.

What I want to do is build alternative worlds, and not just from my own perspective. It shouldn't be about "my world." I'm interested in pluralistic, collaborative world-building—something shared. My PhD research is all about 'open worlding'. So, the proposition here is that the artwork could be the starting point, and everyone who enters it helps build that world. Their conversations could be folded into future iterations.

You recently presented alongside a brain organoid scientist. What happened?

After the talks, the audience grilled me about AI ethics—which models I was using, data scraping, power centralisation. Meanwhile, the scientist was literally describing taking brain matter from dead people, hooking it up to spinal material and running blood through it—basically a Frankenstein experiment—and nobody asked him a single ethical question!

There seems to be a double standard. Perhaps because art is viewed as unnecessary, it gets judged differently. Scientists have a different type of value to their work, or maybe an escape clause (!): "This is for medical research" or "It could treat brain disorders." Even if they're doing something which really pushes at the limits, it's framed as essential. Then the ethical burden falls on artists for using AI. It says something about how we allocate scrutiny and what we value, and also the small worlds we are stuck in.

That tension came through in the workshop also didn’t it.

Yes - there was some pushback against using AI full stop. I find it strange that people would choose not to engage with something just because they know it has been made by AI. Of course, I understand the justified criticism of centralised power of large language models, resource consumption and copyright. AI is having an extreme effect on our lives and that which is to come, so I think it's our job to experiment with these technologies, question them, expose them, work with them in ways they are maybe not supposed to be used for. I think we need to engage and think with AI. There is a new book by Katherine Hayles that's coming out called 'Bacteria to AI', which proposes an 'integrated cognitive framework', that I think is important in this argument –that is not separating or focusing on just human forms of intelligence. AI, other creatures, they all have cognitive abilities, human intelligence isn’t the only form and AI shouldn’t be about replicating human intelligence, but about recognising and including non-human ones.

What's next for your practice?

I'm thinking about building not just fictional worlds, but alternative realities people can engage with—developing scenarios, structures, even speculative policies. Something that moves beyond the aesthetic encounter into participatory, generative experiences. I have just started my PhD, and will be developing my research about ‘Open Worlding’ how art has the potential to build new worlds and realities from the catastrophe of the present. With rationalism, capitalism, and technological control currently unravelling, this creates a ‘crisis of reality’, and in the void of possibility in which we are now living we need the tools for building new worlds more than ever. I think this proposition needs to be grounded in ‘ecological reality’ rather than just human imagination and cognition to diversify possibilities and futures.