Ukraine war: Russia has the upper hand in the ground war – but at sea it’s a different story

The past few days have marked a significant moment in the maritime war between Russia and Ukraine. On Monday July 15, Ukraine’s navy spokesman, Dmytro Pletenchuk, claimed: “The last patrol ship of the Black Sea fleet of the Russian Federation is bolting from our Crimea just now. Remember this day.”

This symbolic milestone is a reminder of Ukraine’s consistent success on the maritime front of the war. While Kyiv’s ground troops continue to struggle and cede ground at points along the battlefield, particularly in the east of Ukraine, it’s a different story at sea.

Despite starting the war with a massive numerical advantage, Russia’s Black Sea fleet has been unable to contribute to the war in any meaningful way. Moscow has lost control of the Black Sea, while even Crimea’s ports – including Sevastopol, traditionally a symbol of Russia’s power – can no longer be seen as safe bases for its warships.

A depleted Black Sea fleet

Ukraine does not have an operational navy – it has no major surface warships or submarines, and just a handful of small patrol boats. Yet Kyiv has developed a credible capability to destroy Russia’s warships at long distances – as far away as Crimea – using missiles and maritime drones. It’s an object lesson in the changing nature of maritime warfare and the growing power of asymmetric weapons – that is, weapons that cost much less to manufacture than the warships they are destroying.

It’s a major problem for Russia because warships are among its most expensive military assets, with a procurement cycle that can span decades. And Vladimir Putin’s depleted Black Sea fleet cannot be reinforced with warships from Russia’s other fleets because of the application of the Montreux Convention by Turkey. Signed in 1936, this regulates naval traffic through the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits in Turkey, including that nations at war can’t move warships through these straits.

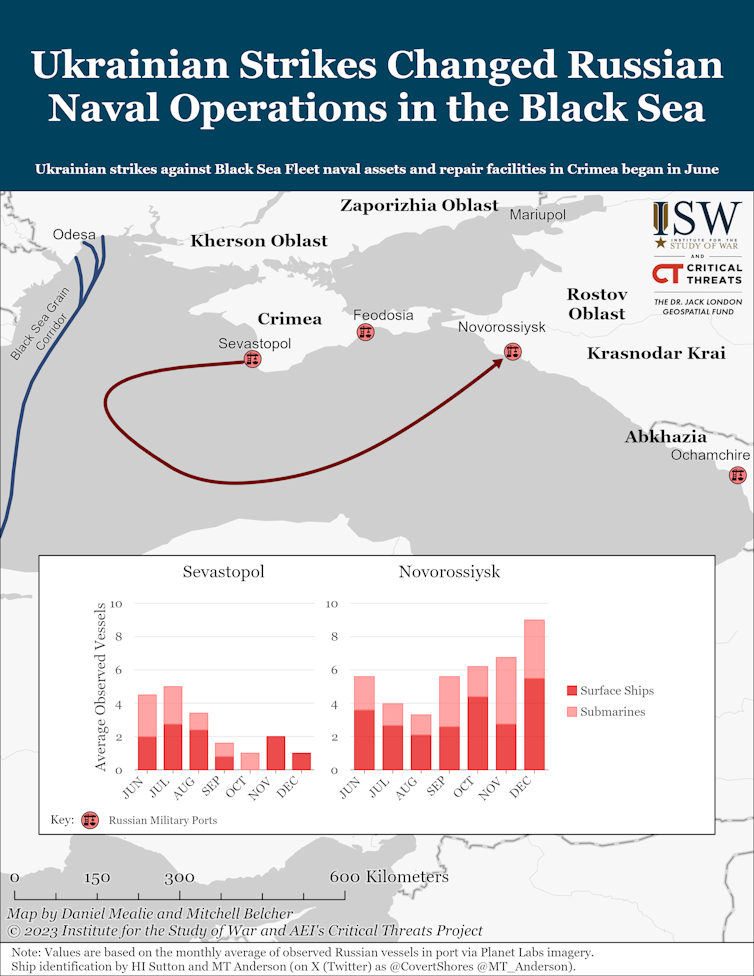

Moscow has no choice but to protect its remaining warships in the Black Sea, which explains the frequent “redeployments” further away from Crimea – in particular, to the port of Novorossiysk.

Diminishing operational options

Since Russian surface warships cannot operate safely, especially in close proximity to Ukraine, some operational options are now out of the question – such as launching an amphibious assault on Odesa. Even providing logistics to troops on land is proving a challenge, while Moscow’s eventual failure to blockade Ukraine – in particular, its grain exports – has been instrumental in sustaining Ukraine’s economy.

Russia’s Kilo-class submarines are still relatively safe when underwater, and are able to launch Kalibr cruise missiles against targets in Ukraine. However, it is unlikely these submarines will be decisive for Russia’s air campaign against Ukraine’s energy and civilian infrastructures, given their limited offensive threat compared with Ukraine’s resilience to damage. But they can still make a limited contribution to Russia’s overall threat to Ukrainian air defence systems.

At a symbolic level, Ukraine’s successes at sea constitute a political blow for Putin. Crimea is central to the president’s narrative of Russia’s revival as a “great power” that, on the domestic front, is a pillar of his regime.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s frequent successes against the Black Sea fleet are boosting morale, at a time when it is increasingly difficult to motivate Ukrainian soldiers fighting on the ground for a long time without seeing “concrete” advances. The symbolic value of these successes should not be underestimated in the context of a long war of attrition.

Crimea as a breaking point?

For the past 12 months and more, the focus of the war has been on land, where Russia has consistently been making incremental gains. Yet Ukraine’s constant successes at sea are meaningful. They contribute to a trend that started in April 2022 with the sinking of the cruiser Moskva, and in July 2022 with the retaking of Snake Island. In all, Ukraine has destroyed or seriously damaged at least 27 Russian naval vessels.

This is not just a victory against Russia’s naval forces: these successful attacks shall be understood in the broader strategic, operational and tactical evolution of the war in Crimea.

By December 2023, Russia had moved most of its naval assets away from Crimea. Institute for the Study of War

Pressures on Crimea are strategically important. Kyiv is targeting naval assets, air bases and air defence systems, as well as transport infrastructure including the Kerch bridge – a vital supply route for Moscow into the peninsula. These attacks have been boosted by the use of west-supplied long-range missiles.

This obliges Russia – for which the loss of Crimea, or even a major setback there, would be catastrophic both militarily and politically – almost to operate on two fronts.

On the mainland of eastern Ukraine, particularly in the Donbas region, Russia has a massive numerical advantage. But in Crimea, where Ukraine can implement an agile strategy making the most of asymmetric technologies, Russia is increasingly on the back foot. And these successes in the Black Sea and Crimea can divert Russia’s attention and resources away from the land front.

Ukraine’s “victory at sea” will not directly help its forces on the ground – at least, not for now. But any significant breakthrough – for example, if Kyiv managed to finally destroy the Kerch bridge – could significantly change the course of the war.

Original article by Professor Basil Germond was published in The Conversation

Back to News