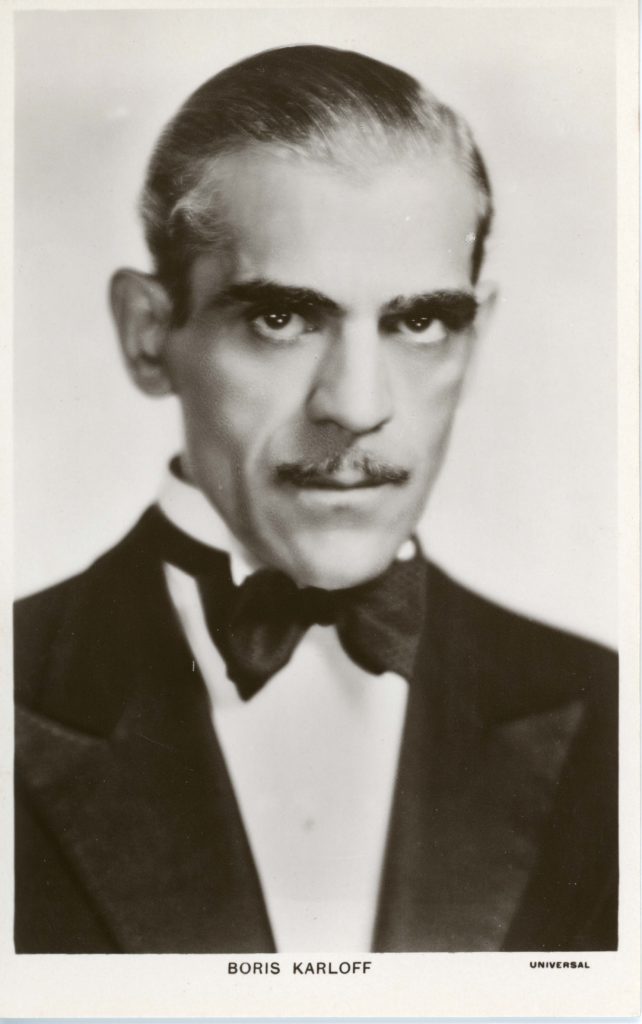

Time for another Picturegoer Magazine postcard as this week’s featured item!

Pictured below is Boris Karloff (1887 – 1869), who was born William Henry Platt in Surrey, England (now part of South London). Karloff is possibly best remembered for his roles within the Universal series of monster films, particularly as Frankenstein’s monster in Frankenstein (1931), Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and Son of Frankenstein (1939), as well as Imhotep in The Mummy (1932). Notably, Karloff was not initially credited for his role in the first Frankenstein, with the credits listing the actor as “?” for marketing purposes.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Karloff maintained a strong screen acting career beyond the 1930s. It is arguable that this was achieved through a willingness to accept roles that could be considered ‘type cast’, as well as diversifying into new media and types of acting role. For example, Karloff continued to star in horror films throughout his life, building on his prestige and infamy as The Monster in Frankenstein along with his striking looks and eloquent but powerful voice. 1963 notably saw the release of two films starring Karloff with acclaimed horror director Roger Corman, The Raven and The Terror. Indeed, 1963 was a busy year for Karloff, as it also saw the release of Black Sabbath, directed by Italian low-budget horror specialist Mario Bava. That name may be familiar to you… Originally known as ‘Earth’, four young musicians from Birmingham wanted to change their name to avoid confusion with similarly named groups and ideally they wanted a moniker that reflected the dark and heavy form of music they played. By chance, across the road from their rehearsal space in 1969, a local cinema was showing Black Sabbath. Ozzy Osbourne, Tony Iommi, Bill Ward and Geezer Butler decided to adopt the name and pioneered what we now call heavy metal (Froese, 2012: 20).

Beyond influencing horror (and inadvertently aiding the fledgling career of Ozzy Osbourne!), Karloff also took the opportunity to turn his hand to acting on the small screen. Indeed, he was an early adopter, starting his television career in the late 1940s and continued to appear in a number of television series over the remainder of his career, usually in a cameo or guest-starring role. Karloff also took advantage of his unique voice, becoming a voice actor for various spoken-word adaptations, ranging from Shakespeare to Peter and the Wolf . It is perhaps a combination of his television and voice acting work that Karloff is most famous for in the latter stage of his career, having narrated the made-for-television adaptation of How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1966). How the Grinch… has become a staple of Christmas time viewing, with Karloff’s poetic and entrancing narration having become a common point of parody and homage within popular culture. Somewhat poetically, the man who became known for playing a monster, a figure of fear and who infamously drowns a young girl in Frankenstein, rounded out his career by becoming a voice of Christmas cheer and reassurance for countless children and families.

Froese, B. (2012). ‘”Is It the End, My Friend?” Black Sabbath’s Apocalypse of Horror”‘. In Irwin, W. (ed.) Black Sabbath and Philosophy: Mastering Reality. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell