Blog: Ouch! The carbon cost of academic collaboration

Professor John Quinton explains how he has tried to cut down on his flying carbon footprint, as part of a campaign to reduce Lancaster University’s growing emissions from flights.

It doesn’t take a rocket (or a soil) scientist to understand that if you fly then the carbon emissions associated with those flights will dominate your personal carbon budget, dwarfing the contributions associated with driving or a meat orientated diet (if you have one). Academia is an international game. Collaborations span the globe, and meeting new people, debating and sharing ideas is a big part of the job. This often means travel for research, discussions or conferences, either on the same continent or beyond. Some of these trips are deeply rewarding and lead to new insights that would otherwise be impossible to gain.

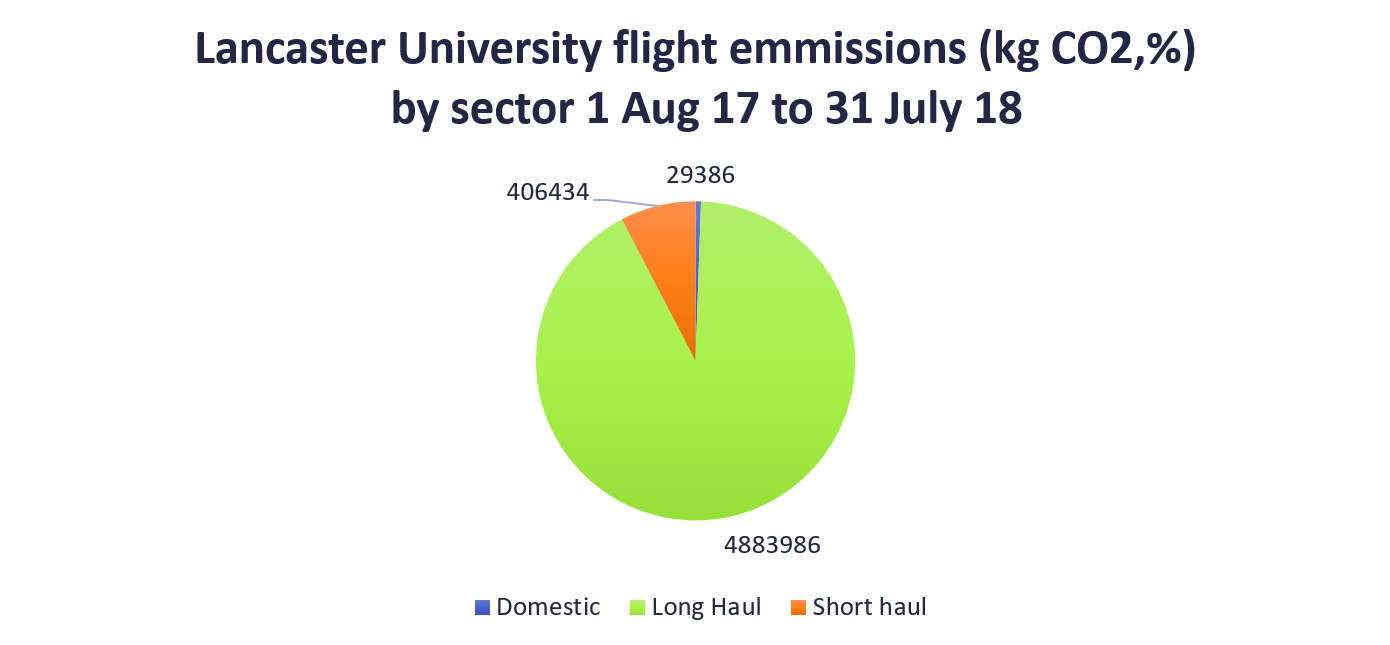

All this travel means academics may have a large CO2 footprint. Lancaster’s data from its travel provider shows that between August 2017 and July 2018 University travellers burnt through 4450 tonnes of CO2 [1] (from almost 25 million kilometres flown) with long-haul accounting for 90% of the carbon emissions. That’s 3.5 tonnes of CO2 [2] for each member of academic staff - ouch! [3][4] This is a significant addition to Lancaster University’s last reported carbon emissions 1 from campus energy use and vehicles of 18, 693 tonnes CO2 yr-1 (reduced from over 25,000 in just 5 years).

The Lancaster Environment Centre Sustainability Group is holding a High Flying workshop on 26 September to discuss how the University can reduce its flight emissions. So it seems like a good time to write about my experience trying to do this.

A pie chart showing 29,386kg of emissions for domestic flights, 406,434kg for short haul flights and 4,883,986kg of emissions for long haul flights between 1st August 2017 and 31st July 2018.

So how did I do in 2018? My profile is a little different to the University as a whole. In 2018 my flights accounted for 7.9 tons CO2, 59% of this associated with long-haul economy and 41% associated with short-haul flights- way ahead of where we need to be to start to push our carbon emissions back into balance and twice that of the average Lancaster academic.

Feeling chastened, in late 2018 I decided to explore what I could do to reduce the number of flights I took. I have research collaborations around the world, including funded projects in China, Kenya, South Africa, and an EU Horizon 2020 project with many EU partners. This international portfolio means I need to travel - but how painful would it be to reduce it? Without committing myself to a one-way journey to China of six days on the trans-Siberian express, plus another two to get from Lancaster to Moscow, addressing the intercontinental travel looked difficult. Although this generated the larger proportion of my CO2 emissions in 2018, my short-haul travel still accounted for a big chunk. So, could I at least do something about my European travel? I took my first tentative steps towards exploring low emission travel (LET).

My first LET trip was in December 2018 from Lancaster to Augsburg in Bavaria, Southern Germany (1492 km) [5] where I have a German Science Collaboration grant. Following a night in a slightly dodgy Airbnb near Kings Cross I was on the first Eurostar out of London, time for a Parisian café visit, and then a train to Stuttgart (nice museum) and on to Augsburg. Journey time from London just over 10 hours – 10 hours to think, write, work , relax a bit and, yes, answer emails! It felt good and it was good: I arrived relaxed and feeling a little better about myself!

My next mini LET was from Vienna to Augsburg, a mere 5 hours (528 km), followed by 10 hours from Augsburg to Rome (926 km) and then back again, in total a saving 0.44 tonnes of CO2 compared to taking the plane.

All well and good, but there was other European travel. I flew to Vienna and back from Munich – why didn’t I take the train? No surprise that time and cost were the main barriers.

Firstly time. To arrive by the evening in southern Germany or Vienna requires either an overnight in London – not very family-friendly and accommodation is expensive (hence the dodgy Airbnb). What about something a little further away? Cordoba (1882 km), in Southern Spain, where another of my collaborators is based, requires a bit more time (24 hours including an overnight sleeper). The plane makes Cordoba possible in just 9 hours (a saving of 13 hours – although not as much of a time saving as I thought so perhaps I’ll be on the train for my next trip).

As for cost, from my limited experience, the cost of the train ticket is higher than the air ticket if you book your air travel in advance, but costs can sometimes be similar if you leave it to a few weeks before departure.

My experience suggests that it isn’t easy and LET involves hard choices and even some sacrifices, so is there anything that the University could do to make it easier? Here are few of suggestions [6]:

Suggestions

Lead from the top

- A commitment from the University, that matches its efforts in other parts of its carbon footprint, to reduce short-haul and long-haul carbon emissions year-on-year and reporting its progress against targets

Ideas around reducing travel:

- Ensure we value local and national research

- Continually improve video conferencing facilities

- Think carefully and responsibly about international teaching ventures and how to minimise the number of faculty flights

Ideas on reducing emissions from travel

- Have a no domestic flight policy (this could cut out 29T of CO2 emissions)

- Remove ‘cheapest option’ guidance from the travel system and include ‘lowest carbon’

- Avoid offering flight options that are not direct (most of the emissions are in take-off and landing) or involve extra distance, for example flying from London to Nairobi via Dubai instead of direct incurs an additional 2020 km (0.36 tonnes CO2)

- The University travel service should provide a train option for any European city that can be reached in a day

- A fund for hotel stays in London to allow staff to take the early Eurostar and to subsidise train travel if it is more expensive than the plane

- An extra day’s leave for staff making work journeys by train (it has also been suggested by the charity 10:10 that employers should give additional time off to staff using international train services for their vacations)

Making travel count

- Encourage and enable staff to combine journeys when travelling abroad

Offsetting

- Increasing carbon sequestration on our estate, for example continuing to support projects like Forests for the Future at Forrest Hills

- Restoring the peat soils of our uplands (as a soil scientist I would say that wouldn’t I!)

Footnotes

- Data supplied by Key Travel for period 1/8/17 – 31/7/18 includes radiative forcing taking into account the high altitude release of CO2. Long haul is the sum of long haul from the UK and onward long haul from a European hub e.g. Amsterdam

- Based on Lancaster annual review 2017 Academic staff number. Assumes all travel academic and not professional staff.

- I assumed that all travel booked through the University’s provider was academic. In reality professional staff and some student travel will also be booked in this way. The numbers will also miss travel booked by individuals outside of the University provider.

- These numbers are similar to the 2 million kg yr-1 CO2 associated with air travel in 2015 and 2016 (normalised to a 12 month period) at the University of British Columbia which equated to 2012 kg CO2 yr-1 per traveller. Wynes et al., Academic air travel has limited influence on professional success. 2019. Journal of Cleaner Production. 226:959-967

- Based on a Google Maps car journey

- Thanks to Jess Davies, Peter Fiener and Andrea Grimshaw for useful suggestions