Firms that exploit the dark side of technology will find it leads to losses as well as gains

02 September 2015

Following allegations of harsh working practices at Amazon, Monideepa Tarafdar talks about the dangers of technology in the workplace.

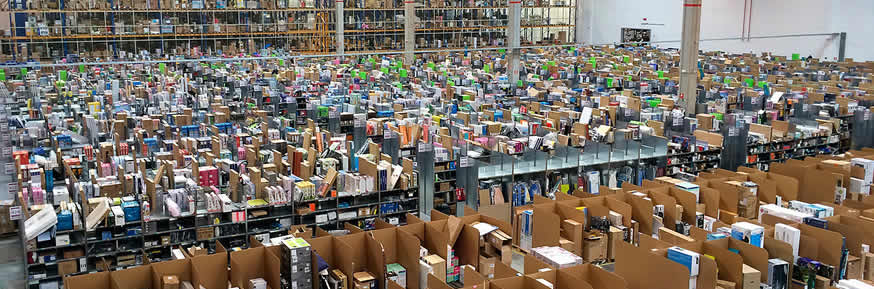

Has technology enabled us, or enslaved us? This is a question posed by recent coverage of the apparently unsettling working practices and work culture at Amazon, among others. The employee monitoring, long hours and continuous performance measurement reported in the New York Times wouldn’t be possible without modern information technology. It seems for some the world of office work has become, as the article states: “more nimble and more productive, but harsher and less forgiving”.

The irony is that the very qualities of modern technologies that we find helpful and increasingly cannot do without – constant availability, reliability, mobility, speed and user-friendliness – also cause a number of negative effects. We like that technology-enabled flexibility allows us to work from home when our child is sick, but the same flexibility and reach make us contactable at all hours on all days, and may turn us into email addicts if we are not careful.

The near-infinite options and capacity for customisation offered by today’s app-driven devices leads us to tinker, experiment and discover ways to use them that may not be good for us – individually, or collectively.

It giveth, and it taketh away

One of the examples given for the Amazon work experience was of emails arriving past midnight, with subsequent emails asking why they were not answered. Recent research shows technology causes “technostress”, which reveals itself in a number of ways.

Because information comes at us so from so many sources, we feel forced to work faster to process it all, and take on more than we can handle. Because our colleagues might respond immediately, we feel the pressure to adapt and increase our pace. Keep this pressure up 24/7 and we find ourselves working during holidays, during family time and social engagements, and our lives are invaded by the same technology we value.

Worse is the more recent experience of “FOMO” – the fear of missing out – where we feel anxious and insecure that if we’re not sufficiently connected and up-to-date then others may get ahead, or that socially we may miss out.

Employers can play upon such fears. For example, Amazon’s internal phonebook instructs colleagues on how to send anonymous feedback on colleagues, such as perceived “inflexibility” or “complaining about minor tasks”. When enough staff experience these effects and feel that work tasks should be immediately attended to just because they’re available through a smartphone, an institutionalised work culture develops where technostress is the norm rather than something to be avoided. It’s worth noting here that research links technostress with reduced satisfaction, productivity and innovation – and so offsets many of technology’s purported benefits.

Technology is what we make of it

So what do organisations do about this dark side to the technology with which they equip their staff? They can use it to serve a command and control work culture if that what they want to create. Such technocratic cultures are easily brought about today, and far more powerful and insidious than Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon.

Or companies can go to the other extreme, such as preventing access to email servers outside working hours which robs the firm and their employees to some extent of the benefits of technology altogether. Neither is entirely desirable.

However, we’re beginning to see some examples of thoughtfulness and deliberation in the way organisations deal with technostress. For instance, in the UK Vodafone provides awareness programs to employees on the potential dangers of not knowing when to shut off from work while working from home.

Or, research which shows that our interaction with technology depends very much on the individual and their situation, which indicates a need to take into account the varying nature of organisations and staff when trying to set out policies that could help change the way we use technology for the better. In any case, at a very minimum an awareness of this dark side is an important first step.

From steam engines to railroads and to factories of mass production, technology has been the primary structuring force in our economic enterprise. The tussle between whether technology works for us or the other way around is not new; what we are seeing today is this tussle played out at scale and speed. What we need to ensure is that it is we who use our technology, rather than allowing it to use us.

![]()

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Images Álvaro Ibáñez | CC BY 2.0

| Follow the discussion via The Conversation comments |

Disclosure statement

Monideepa Tarafdar does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.