Cost of student visa clampdown weighs heavily on colleges

18 July 2014

Geraint Johnes says that targeting students and universities as part of a broader migration policy is neither appropriate nor innocuous.

The British government’s recent decision to suspend the licences of one university and 57 private further education colleges to sponsor international students has generated shockwaves across the sector. Another two universities are no longer able to sponsor new international students, pending further investigation. Overseas students bring in substantial revenue to higher education, and the denial of access to this income source will present the affected institutions with significant financial challenges.

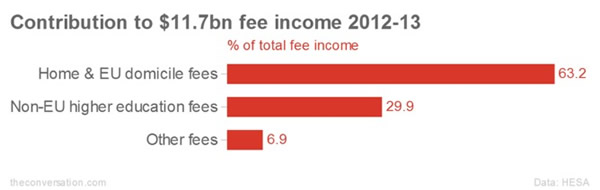

Across the sector, 30% of all fee income comes from students domiciled outside the UK and EU.

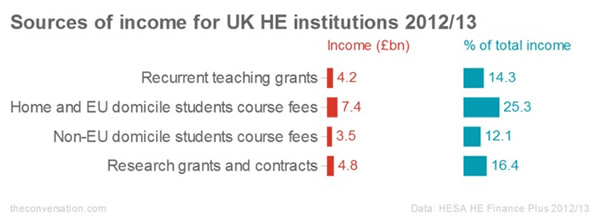

Of course, universities also have other sources of income – from research activity, endowments, funding council grants and so on. But on average overseas student fees still account for more than 12% of all revenues in the sector.

The financial sustainability of some institutions is clearly put at risk by the recent move. A report in Times Higher Education points to ongoing financial woes at one of the affected universities, Glyndwr. Whatever the rights and wrongs are of the decision to withdraw the licences to sponsor international students, all of the affected institutions have a clear incentive to respond quickly by changing their procedures in order to restore confidence.

Where responsiblity lies

It is entirely appropriate that students entering the UK to study should be able to demonstrate they have the prerequisite set of skills – and this includes ability to learn in the language they will be taught in. Higher education providers should not admit students without these skills, and they should take reasonable precautions to ensure that they do not.

In so doing colleges often rely on tests conducted by third parties, most of which are very reputable. But a BBC Panorama investigation in February 2014 provided evidence of fraud in one of the testing systems.

Ensuring that students who ought not to be admitted are not let in requires integrity both in institutions’ own admissions procedures and in the testing mechanisms. If sanctions are to be imposed on higher education providers, it needs to be clear that it is these providers themselves that are responsible for the failure in the selection process. But institutions that have innocently relied on testing systems that are now shown to be suspect should not be penalised for the shortcomings of those systems.

Damaging migration rules

The decision to withdraw licences to sponsor international students only reinforces the rhetoric surrounding the government’s stance on migration. Although qualified students remain welcome to study at UK institutions of higher education, this rhetoric has served to make the UK a tougher sell for universities.

This has become a particularly acute problem with the government’s persistent with a policy to include students within its net migration target, despite widespread calls for a change to its policy.

Changes in visa regulations mean that overseas students graduating from postgraduate programmes are no longer entitled to stay in the UK for a couple of years to work once they complete their studies. This was an entitlement that many used to take up as a means of paying for their studies.

All of this means that institutions with unimpeachable admissions processes have been adversely affected too, as Cardiff University’s vice chancellor Colin Riordan has pointed out on The Conversation. The overall number of Indian students coming to study in the UK fell by almost a quarter in a single year following announcement of the visa change in 2011-12. It fell again in 2013.

The wider impact of this is significant. Using a methodology that I developed ten years ago to evaluate UK export earnings due to overseas students, the latest data suggests that the value of such exports amounts to well over £10bn each year. Constraints on the ability of our higher education institutions’ ability to sell their services have a non-trivial effect on the UK’s export earnings and GDP.

Effective controls do need to be in place so that students attending UK universities are equipped to benefit from the experience. That should be the driver. Let’s bear in mind that students are typically not migrants at all, but rather consumers seeking to buy and take home a successful UK export. So targeting students and universities as part of a broader migration policy is neither appropriate nor innocuous.

| Follow the discussion via The Conversation comments |

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed in our Comment and Analysis articles and in any attached comments are personal, and may not reflect the opinions of Lancaster University Management School. Responsibility for the accuracy of the information contained within these articles resides with the author.

![]()

Geraint Johnes received funding from the British Council and a consortium of government departments in 2004 to develop the methodology used to evaluate exports of education.